A week ago, I was at the Clark Museum in Williamstown, Massachusetts. It is an odd museum, the collection of the heirs of the Singer Sewing Machine fortune. There is no overarching character to the collection – impressionists here and there, modernists here and there, tea pots and silver platters in another room. It is a collection of wealth – where what was bought was purchased because there was money on the table, not necessarily ideas to guide the curation.

Turning into the main room, one is struck by a very moving painting by John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) from 1880 called Fumée d'ambre gris (Smoke of Ambergris). It is based on a trip that Sargent – the American painter – took to North Africa in the winter of 1879-80. He began this painting in Tétouan (Morocco). Sargent hired a model to stand in the patio of his rented house. He sketched her and then finished the painting in his Paris studio. The painting depicts a woman perfuming her clothes. It is dream-like, a cliché of Orientalist paintings of this period.

The spirit is captured in Mark Twain's Innocents Abroad (1869), where he writes of his time in Tangier (Morocco). He had seen the Orientalist art, and it was about this art and his eyes that he wrote, 'Here is not the slightest thing that ever we have seen save in pictures – and we always mistrusted the pictures before. We cannot any more. The pictures used to seem exaggerations – they seem too weird and fanciful for reality. But behold, they were not wild enough – they were not fanciful enough – they have not told half the story. Tangier is a foreign land if ever there was one'.

I can imagine Edward Said walking through the gallery, looking at the Sargent, sniffing at the caption, wondering about the Mark Twain quote, thinking about his own frustration with the way it had become so easy to make the 'Orient' so exotic – and erotic.

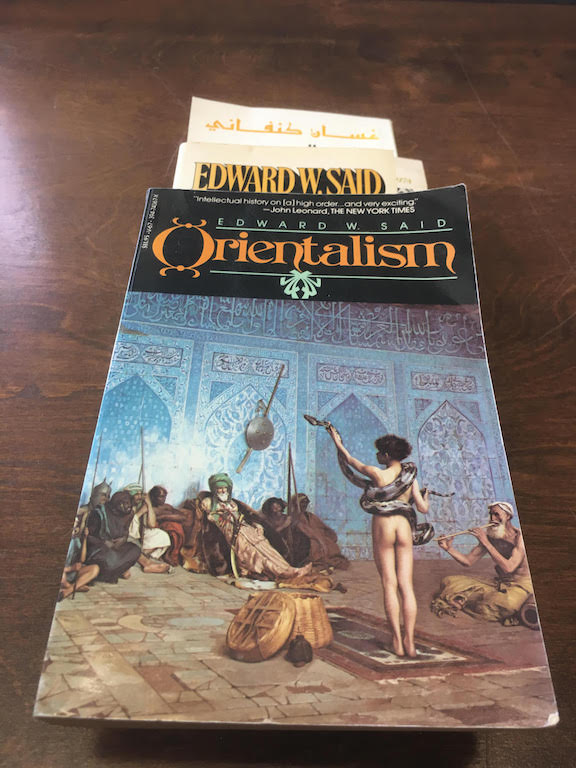

Across the doorway, I was stopped by the next painting. It was Jean-Léon Gérôme's Le charmeur des serpentes (The Snake Charmer, 1880) – above. Gérôme painted this in his Paris studio at the same time as Sargent was working on his own painting. It is the painting that appears on the front cover of Edward Said's Orientalism (1978), which sits on my table here alongside The Question of Palestine(1979), The Disinherited by Fawaz Turki (1974) and Ghassan Kanafani's Rijal fi al-Shams (1963).

The painting has an interesting history. If you look at it closely, the wall behind the men is styled from Gérôme's memories and sketches of what he had seen in 1875 when he visited Topkapi Palace in Constantinople (Istanbul). Gérôme is said to have modeled the tiled floor from a mosque he had seen in Cairo. As the note in the museum put it, 'the spectators represent a range of ethnicities, wearing a mishmash of clothing and weapons'. There is something scary about the men – is it lechery for the naked boy or marvel at his manipulation of the snake?

The painting, which was first sold to the US collector Albert Spencer for 75,000 francs and then for $19,500 to Albert Corning Clark in 1888, was sold to a gallery in 1899 at a loss. Albert Corning Clark's son, Sterling Clark, bought the painting back in 1942 for $500 – the low point of Orientalist art. He then put it into his museum in 1955.

How did Edward Said pick the painting for the cover of his book?

Richard Rand, the former curator of the Clark Museum, has a memory. 'I once had the occasion to talk to Said about it, and he said he was driving through the Berkshires, stumbled on the Clark, and knew the moment he saw the painting: That is the cover of my book'.

I asked Mariam Said, Edward's wife, if this was the whole story. Mariam told me that the publisher – Pantheon – 'thought the cover should be an orientalist painting. Gérome was on top of the list. They sent Edward pictures of several paintings – two by Gérome and the rest by other artists.The minute Edward saw The Snake Charmer he said this is it. It was by far the most complex and conveyed exactly what the book was about'. It was only later – in the late 1990s or early 2000s – Mariam recalled that 'Edward and I saw the original when Edward was invited to give a talk at Williams College in Williamstown'. 'I thought the painting was amazing', Mariam said. 'It talks to you. Edward was very excited seeing it at last'.

The painting itself provoked discussions between Edward and the publishers. He worried – Mariam says – that the nudity of the boy 'may not be appropriate'. But ultimately this was the painting chosen for the cover.

Strikingly, Edward did not discuss Gérome or the painting in the book. It was left to the reader to decide how to assess the cover. Other pictures were chosen for other editions.

Gérome's Orientalism does not exhaust the range of representations. There are many Orientalist visions of the snake charmer Gérome did two paintings on the theme, while Edwin Weeks, Fabio Fabbi, Charles Wilda and others did at least one painting with a snake charmer. Many of these are dull paintings, relying upon old Orientalist tropes for excitement with the paintings themselves as flat as could be.

But even here there are exceptions.

One painting that does come to mind is in Sydney (Australia) – the Art Gallery of New South Wales. It is Nasreddine Dinet's Le charmeur de vipères (1880). Dinet was born Alphonse-Êtienne in 1861, but changed his name to Nasreddine when he converted to Islam fifty years later in Algeria. Dinet had first been to Algeria with a group of entomologists in 1884, fell in love with the country and moved there in 1903 to Bou Saada. In 1889, Dinet also painted a snake charmer. But his painting is so different from that of Gérome. Here as a painting that glimpsed at the Algerian people with great feeling and sensitivity. It is painted in Laghouat, a town further south than both Algiers and Bou Saada.

Another exception is also perhaps an answer to Orientalist art. It comes from Abdelaziz Haounati – who lives in Agadir (Morocco). He has his own Cubist take on the snake charmer. It is below.