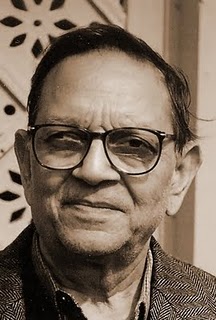

Image Courtesy: Hindi Kunj

Image Courtesy: Hindi Kunj

Arundhathi Subramaniam (AS): What are the directions your poetry has taken over your six poetry collections? Would you trace the trajectory of your journey from one book to the other—in terms of themes, preoccupations, and the approach to form? Have there been changes in the way you define your poetics?

Kunwar Narain (KN): I was 28 when my first collection of poems, Chakravyooh, came out. I had started writing in English earlier, and European romantic poetry was a strong influence in those formative years. Specifically, I responded better to the French Symbolists like Baudelaire, Mallarmé, Verlaine, Rimbaud, etc, than to the English Romantic poets. There are poems in Chakravyooh that reflect the Symbolist influence. Free verse, for instance, helped me modify the strict Hindi metrical forms with greater freedom and innovation. I could feel an instinctive affinity with the Sanskrit varnik metres that have a similar structure – word-counts matter more than stresses and rhymes. Hindi words have a long and fascinating etymology – they have meanings but, more than that, a culture and a history. They have an immediacy but, more than that, a personality that can be evoked in poetry to speak of the experiences and adventures that the word has passed through over the ages to arrive at its present meaning. In that sense, Chakravyooh was my first “adventure” in the wonderland of words!

But I did not entirely abandon the Hindi mātrik metres. In Parivésh: Hum-tum, which came out five years later, free-verse and metrical poetry co-exist. But, linguistically and socially speaking, it is a more varied world that my poetry moves in and around. I am never in a hurry to publish collections of my poems. Five to ten years apart, they are ‘joined’ by time and space; gaps similar to the gaps joining two words; apparently blank spaces, but not really so. In a sense, the different collections are interlinked and can be read in a continuum, reflecting my response to the changes taking place within me and in the realities around me. Ātmajayee (a short epic based on the Kathopanishad and published in 1965) is very different from my other collections. It is my response to death, which every individual has to face in life. A creative life, to my mind, seems to provide some sort of an “intimation of immortality” and a distraction from the fear of death. Poems in Apné Sāmné (1979) relate more directly to the socio-political mood of the country that preceded and followed the Emergency. In my later collections, Koee Doosra Nahin (1993) and In Dino (2002), I tried to broaden my view of human life and the world we live in. To call this view simply global would be too gross for the wider concerns of myth, history, culture, and progress, etc, that it seeks to embrace.

Poetry is a sensitive and imaginative way of expanding our comprehension of the life we face—and it can be fruitful to read some of my poems in that way. It is not only the experiential world but also the imaginative world that combine to form a total life reality. I have never tried to force any kind of “poetics” on my poems, but rather let them freely determine their own “form” and “content”. Marx’s view that “form” is the form of its “content,” or the old Sanskrit quote of Jagannath (c. 17th) “shabardthau-sahitau-kavyum” (poetry is a pleasant fusion of word-and-meaning), essentially sum up for me a working definition of poetical practice.

Apurva Narain (AN): How were you attracted towards literature? Tell us something about your earlier experiences.

KN: I was attracted to books from very early on and spent considerable time reading and scribbling on my own. I started writing poetry when in University—first in English but soon in Hindi. The poetic process, like any other creative process, is complex and cannot be explained in very unequivocal terms. It has deep roots in life and language and there is something genetic about it; not very different from a, sort of, biological evolution. That is why, after a certain stage in the growth of a poet, it becomes nearly impossible to objectify (or resist) his creative identity and explain it as an independent entity. One can critically examine his poetry; but can never, perhaps, explain rationally how it came to be that way. I feel a bit of this about myself.

In 1955, I visited Poland, Russia, and China, and had the chance to meet poets like Pablo Neruda, Nazim Hikmet, and Anton Słonismkie in Warsaw—these meetings meant a lot to me at that age, and were added triggers to my attraction for poetry. Lucknow’s literary life in those years was also very rich with regular discussions at its Coffee House and weekly literary meets of the “Lekhak Sangh” with fellow writers. This period also offered me opportunities to meet many literary, academic, and political elders. A close association with Acharya Narendra Dev, Acharya Kripalani, and Dr Ram Manohar Lohia—who were like family members—contributed considerably in shaping my thoughts and diverted me towards literary pursuits away from my family business background. I consider all these experiences vital to my literary make-up.

AS: You have translated several international writers—Borges, Cavafy, Walcott, to name a few. How has the process of translation, a creative one in its own right, moulded your own poetic practice?

KN: I believe that the best way to know a good poet is to try to translate her or him. I learnt a lot when I tried to translate Mallarmé directly from the French into Hindi with the help of my French teacher. My translations were far from Mallarmé’s originals. But the rich experience of freely handling that rare poetic material gave me an insight into poetry far more valuable than a pursuit to translate him literally could have ever given. Translating Cavafy, Borges, Walcott, and, more recently, Gunter Grass in collaboration with German translators, has similarly been a most rewarding experience. All these poets are vastly different from each other, and that helped me discover different facets of poetic craft. Poetry is often a strongly culture-specific and language-specific art, and there is a kind of poetry that makes little or no sense in literal translations—unless it is, sort of, “rewritten” in the receiving language. Most Urdu poetry, for instance, is highly culture/ language-specific. Ghalib’s andāz-é-bayān (way of saying) is simply impossible to translate. One important difference that I found while translating different kinds of poets is that no one language is equally competent to “receive” all kinds of poetry. There can also be varieties of translatable and untranslatable poetry in the same poet. While translating Grass, for instance, I found that it was easy to translate a poem like ‘Saturn’ in Hindi, rather than poems that related to his very specific World War II experiences and which could be better adapted in European languages.

It is the exploratory aspect of translations that has attracted me the most. Instinctively, I have chosen poets to translate who come nearest my own concerns and sensibilities. In Borges and Cavafy, I found a way of looking at life and the past that also seemed relevant to me in the context of Indian history, as I see it. I could have added the names of Gunnār Ëklof and Pablo Neruda as well, whom I admire, but I would never feel comfortable translating them. Poetry derives its craft from many sources, and it has been so in my case too—poets I have translated are only one of these sources.

AS: Could you talk about the ways in which Marxist and Buddhist worldviews have shaped your poetry?

KN: Marxism in the 50s and 60s was a powerful influence on world literature. Its emphasis on grassroots realities, on socio-economic and political solutions of human poverty and exploitation, focussed the much needed attention on the problems of the common man. That his anguish could be alleviated by effective political, social, and economic action seemed to bring the great utopian dream within reach. But soon, the inner contradictions within Marxist politics itself became apparent; and its fascist tendencies in the name of state control, as reflected in the Soviet and Chinese models, seemed to oppress the very people they promised to liberate. A modified Marxism, more liberal and democratic, seems to have soon emerged and stayed in human thought. It is the preferred socialist model of Marxism more than its violent and belligerent version that came to stay in my writing.

I see in Gandhian philosophy a moral revolution in action. A Buddhist world-view has much in common with the Gandhian way of thinking and action. Violent means of revolution are bloody outbursts of raw emotions; the non-violent revolution requires a steadfast solid moral strength best exemplified in Gandhi’s stand against British colonialism. Buddhism, you will notice in my poems, appeals to me more for its history of long survival than for reasons of faith. Its survival has deep roots in its immense tolerance and capacity to adjust, and in not being fundamentalist by nature. Even a casual glance at the various schools of Buddhism that developed and prospered, after Buddha, in India and Central Asia point at the amazing flexibility of this philosophy of compassion. Humanism is the great point where all the great thoughts about man’s well-being converge. I have tried in my poems to keep that point always in view.

AN: Besides poetry, other genres have also been of interest to you. How do these interact with your primary inclination as a poet?

KN: I have been writing short stories, literary criticism, film criticism, and essays simultaneously with poetry from early days—it is often the subject that defines the form. Cinema, drama, music, and art have a lot to do with my poetic sensibilities but they are not extensions of my poetic world; they are extensions of my thoughts and experiences of the world we live in. These keep changing and my poetry, not infrequently, gets a refreshing feedback from these changes.

AS: What, in your opinion, are the challenges a poet faces today? Are there any specific challenges confronting a contemporary Hindi poet?

KN: The fall of a great ideology leaves a great void behind. For more than half a century, a good deal of Hindi writing has been drawing sustenance from Marxist and Modernist theories. Things have drastically changed in the last 15 to 20 years. The nature of inspiration many derived from both has also changed. Their core ideas have been absorbed by a humanistic legacy. We are living now in a post-Marxist and post-modernist world facing new challenges drawn up by the market economy and globalisation. For a developing country like India, where mass poverty, illiteracy, pollution, and corruption are still to be reckoned with, the new changes offer more challenges than hopes. Hindi literature, generally speaking, is well aware of these problems. The response, however, often seems to be more of a hurried journalistic type than of a soul-searching kind. Maybe because the nature of these problems has more to do with rapid superficial changes in our lives than with values deep-rooted in man’s cultural, artistic, and humanistic experiences. The involvement of poetry with either kind of lives provides a complex structure that cannot be defined or explained in simple terms. I have found more poetry in the variety and complexity of life and literatures than in any simplistic interpretation of it.

There is also no doubt that ethnic divides, communal violence, fundamentalisms, and terrorisms weigh heavily on the conscience of every right thinking person today. A number of these problems have roots in present-day Indian politics. The uneasy relationship between a dominating corrupt politics and the marginalised voice of literature is one of the many problems eroding the humanistic culture of the country. I take it as a very specific problem being faced by Hindi poetry.

AS: Borges says “every writer creates his own precursors”. Who, to your mind, are the writers you would consider to be your precursors or exemplars in your creative journey?

KN: Relations with great books that we read, influences, precursors, etc are hardly ever perennial or static—not in my case any way. They keep changing with time, as a poet grows. Even when I return to a past master who may have once been a great precursor for me, the relation is never the same, nor the influence similar. A growing writer’s sensibilities and understanding of his own self and his times tends to determine the way a particular writer, poet or book interacts with her or his own creative propensities. I think that is what Borges meant when he said “every writer creates his own precursors”. I read the Mahabharata for the first time when I was only 15 or 16. The fantastic fight scenes fascinated me. There was great drama in it. As I grew up, I kept returning to the Mahabharata but not for the same reasons. For a long time, the Bhagwad Gita captivated my thoughts and imagination. Now, maybe, it is the Shanti-Parvam that attracts me more. Later, amongst Indian classics for instance, Kabir influenced me for his social and mystical concerns and Ghalib for his superb craft and depth of human understanding. I cherish this dynamic relationship with great writings and find it creatively more fulfilling.

AS: How do you respond to trends or impulses in contemporary Hindi poetry?

KN: My response to trends and influences in contemporary Hindi poetry has been rather lukewarm, at times even negative, when a movement became too rigid. Poetry is, by nature, a free art; and it does not welcome impediments and mandates. I have been writing poetry for nearly half a century now and have seen more than half a dozen literary movements come and go. What survived these is great poetry and not the hullabaloo surrounding them. In fact, it is critics more than poets who give names that, for a genuine poet, matter little. That is how, in Hindi poetry, names like Chhāyāvād, Pragativād, Proyogvād, Nayi Kavitā, a-Kavitā, etc came into being, but good poetry always seemed to be relatively indifferent to these labels. Not infrequently, they were counter-productive in the growth of poetry. When a movement preferred a certain kind of poetry, or a particular poet, as the model type, it encouraged imitation and thwarted originality.

The Modernist Movement had its beginnings in the poetry and literary criticism of poets like T. S. Eliot. Broadly speaking, it meant a new way of looking at the craft of poetry, the traditions, the cultures, the past, experimentation, etc. The impact of modernisation on Hindi poetry can roughly be located in and around the four Saptaks edited by Agneya (four anthologies of seven contemporary poets, each written 1943 onwards). The trends, it will be observed, like Marxist, modernist, experimentalist, new, etc overlap in the poetry of this period as they do even now. As a poet included in the Teesrā Saptak (Third Anthology), I soon realised that poetry cannot be classified that way. It frequently went beyond the characteristics and duties attributed to it by the critics. One does feel that contemporary Hindi poetry now moves in a bigger and freer world, contextually and thematically.

First published in Poetry International Web.

Also read:

प्रेम और दार्शनिकता का कवि