Delhi October 31, 1984. I was just struggling out of bed in my barsati in South Delhi when word came that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had been shot. And had been rushed to All India Institute of Medical Sciences. Those were not the days of mobiles and internet, and one rushed to the hospital to find that the news had still not broken, and hardly anyone was there. I tried to go inside, but was stopped outside the floor where she was (later the entire hospital was cordoned off). Soon a crowd gathered, the reporters arrived in hordes.

We all stood outside waiting for word. She is dead, said someone quoting officials. But then the doctors came out asking for blood. Congress workers lined up to donate blood. We heard Arun Nehru was inside, as was Pranab Mukherjee, and they were waiting for Rajiv Gandhi to arrive from Kolkata I think it was. He came, and was taken straight inside.

As a naive young reporter one believed that Indira Gandhi was not dead, when actually she had been brought dead to the hospital. The delay was to ensure that the mantle of leadership was given to Rajiv Gandhi who was appointed Prime Minister in hospital before the news of his mothers death was broken.

And just as we rushed to our offices to file the reports, word came that violence had begun as Sikhs were reportedly celebrating her assassination by her bodyguards. We thought it would be contained, but soon the fires spread, and engulfed Delhi that was torn apart by mobs hunting down Sikhs for three full days before orders were given to the Army to move in and control the situation. A three days that we who were out on the streets following the mobs, will never ever forget.

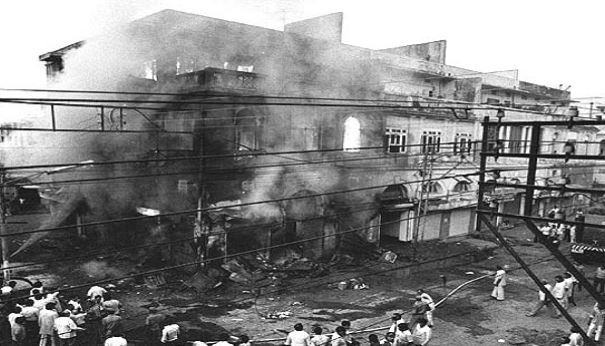

Within hours the capital of India became a ghost town. The police disappeared, the people vanished, and fires and smoke was all that one could see from The Telegraph office in the IANS Building on Lutyens Rafi Marg. Taxi stands—those were not the days of Uber and Ola but the old fashioned black and yellow cabs owned and run mostly by Sikhs—had been set ablaze. The Sikh drivers had run for their lives.

The INS building housing out-station newspaper bureaus was soon deserted. Even reporters seemed to have gone indoors as violence raged across the capital. Photographer Sondeep Shankar and I borrowed someone’s old Ambassador car and set off on a journey that neither of us will ever forget. As we drove we were stopped every now and again by mobs, asking us what newspaper we represented, and whether it was Indian or foreign. We were fortunate enough to be let off with warnings.

On Parliament street a mob had stopped a truck and were dragging out the Sikh driver, terror writ large on his face. We tried to find the cops in the nearby police station but it was deserted too.

We drove to South Delhi colonies, posh Safdarjang Enclave, Greater Kailash. The mobs had reached there too. Lumpens were jumping over walls, breaking down front doors. Neighbours helped the Sikh residents get away. Many were not that fortunate. I have never felt more helpless as a scribe, a bystander unable to stop the mobs, and not even finding a police constable to help. It was as if the streets had been given over to the lumpens, there was no government, no cops, nothing. Just murdering, looting mobs.

The night in the South Delhi barsati was punctured with screams and shouts. The attacks on Sikh households was continuing. The city was swamped with rumours, “the water has been poisoned.” friends telephoned urging each other not to drink water. The tension was palpable, no one slept. My Chief of Bureau insisted on dropping me home in the early hours of the morning. The entire drive of 8 kilometres was like through a movie, with vehicles burning on either side, and charred houses still smouldering, witness to the days assault.

The mornings started early. We heard that all was not right in Trilokpuri. So Sondeep and I got into the white ambassador car and drove down. As we reached, we saw youth scattering from all sides. We realised that they were running from us, thinking that the white ambassador was carrying officials. They all had something in their hands that we later realised were little containers of oil, and perhaps matches. There were bonfires every few feet.

Puzzled about the bonfires we stopped the car and went to the first fire to peer inside the blaze. And to our horror realised that there were bodies being burnt inside. We went from fire to fire, confirming that bodies were being burnt. We started counting the bodies in each bonfire to get an assessment of how many Sikhs had been killed in just that part of Trilokpuri. In the midst of covering violence the picture becomes micro, it is only later that the facts piled up to show that thousands had been killed in Trilokpuri with a large scale attack by the mobs on the hapless Sikh families living here at the time.

On the third day, word came that trains from Punjab were coming into Delhi carrying dead bodies of Hindus. This rumour spread like fire, and I went to the police station expecting the worst. The worst it was, but all the bodies were of Sikhs. I was there from the morning for about eight hours and personally counted 200 bodies. On the basis of the rumours, mobs had collected on the railways tracks to stop the trains, drag out the Sikh passengers, kill them and place the bodies back in the compartments. These death trains then rolled into Delhi railway stations.

For the first time that day, The Telegraph departed from the customary norm of not identifying the religious identity of the victims. I insisted that if we carried the headline ‘200 Killed’ it would feed into the rumour that those killed were Hindus. And hence the editors agreed and the banner headline ran “200 Sikhs Killed….”

Three days etched in a reporter's memory, some of it in photographs. Three days that created havoc with a community. And the horrific violence that left a trail of widows and grieving families but was justified by the Prime Minister of India at a public meeting in the Boat Club lawns—where we stood just below the high platform unable to believe our ears—with, “when a banyan tree falls, the earth is bound to shake a little.”