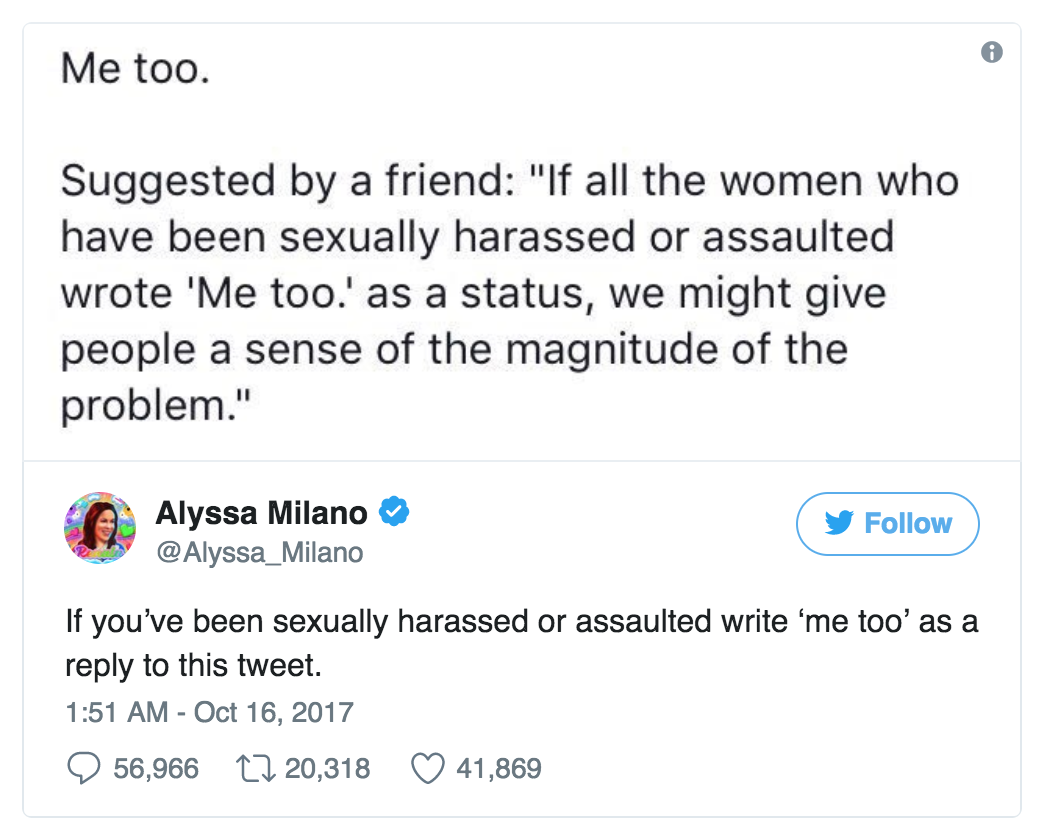

The now viral #MeToo trend started in response to a tweet by actress Alyssa Milano, who urged women to use the hashtag to demonstrate "the magnitude" of sexual assault or harassment. “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote 'Me too' as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem,” Milano posted, with the prompt snowballing into a viral social media movement.

Within hours, #MeToo became a trending hashtag on Twitter, and as of Monday, more than 6 million Facebook users are “talking about” it. Celebrities have joined in, highlighting the harassment and abuse they’ve personally faced — a powerful response in itself as the hashtag was prompted by the controversy surrounding Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, who numerous women have accused of sexual harassment and assault — allegations that the film industry had till recently quietly ignored.

The number of people who have responded to Milano’s tweet does indeed give a sense of the magnitude of the problem of sexual abuse and harassment, and violence against women as a whole.

Yet, while scrolling through the countless #MeToo statuses on my social media feed, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of unease. Although I agree with the movement in principle, I just couldn’t get behind it (and I’ll get to why)…

There are important takeaways from the movement; essential things the hashtag and its popularity have achieved. For one, it demonstrates how pervasive sexual abuse and harassment are — that violence against women isn’t limited to a particular class, nationality or religion. No matter who you are, where in the world you live, what you do, whom or what you believe in — chances are, if you’re a gender/sexual minority, you have faced some form of sexual abuse and harassment.

A few people posted the hashtag in solidarity, but added “Not #MeToo, yet, thankfully” — and clarified that it was perhaps owing to privilege that they were lucky enough to not have experienced any form of sexual abuse or harassment. I don’t think privilege has anything to do with it… yes, it may protect you from lewd glares and groping hands in an overcrowded bus since you aren’t compelled to take public transport, but that’s not what sexual abuse and harassment are limited to.

Sexual abuse could be in the form of an uncle who didn’t understand or respect boundaries while you were growing up, boys who teased you in school as a teenager, a disrespectful boss or colleague in the workplace as an adult, or a man who called you a c*nt for rejecting his advances… the argument that ‘Not #MeToo’ has anything whatsoever to do with privilege is unfounded and even dangerous, as it reduces sexual assault and harassment to an issue of class — which it is not.

The #MeToo movement, conversely, defines the problem of sexual abuse and harassment regardless of various social and cultural constructs, and applies it to all women … and I think this is it’s biggest achievement. Additionally, the movement was even able to accommodate sexual minorities who have been abused, harassed or assaulted, as this abuse also fits into a gender paradigm.

It also flips the onus of shame from the victims to the perpetrators — men, from those who think locker room culture and sexist humour are harmless to those who have physically assaulted a woman (or man, third gender, etc — it all applies), to every grade between. It emboldens women and other victims to speak out, and to recognise that it’s the attackers and perpetrators who should feel ashamed, and not the other way around.

These are huge accomplishments for a viral social media movement, and the #MeToo trend follows a number of social media protests that attempt to raise awareness. There was the #YesAllWomen movement in 2014 — which highlighted misogyny and violence against women after Elliot Rodger killed six people in Isla Vista, California, an attack that was seemingly spurred on by Rodger’s hatred for women. We saw #NotOkay a year ago — a response to a video of Donald Trump bragging about assaulting women. We’ve also seen SlutWalk marches that aim to protest victim shaming justifications attached to sexual assault, and Take By The Night programmes that encourage women to make their experiences public. In India, we’ve seen the success of the pinjda tod movement — a collective protest involving students and alumni of various colleges in Delhi “against restrictive and regressive hostel regulations and moral policing by hostel authorities.”

So why am I having such a hard time getting behind the trend? Perhaps because of the hypocrisy that I can’t help but associate with it. Sexual abuse, harassment and violence against women is a deep rooted social problem — and is very directly linked to the pervasive culture of patriarchy.

Posting a status saying #MeToo has very little significance unless we engage with the larger social context that condones and perpetuates a culture of violence against women. This culture takes on a different form in respect to your personal context … be it less pay than a male colleague at a law firm in New York, a bride price attached to you in a village in Jharkhand, or the custom of karva chauth in most Indian households.

The last example hits home a little harder, as a lot of people on my social media feed who are posting #MeToo are often oblivious to the larger culture of patriarchy that informs and dictates their everyday lives. They go on to defend deeply patriarchal practices in the name of “tradition” — and while I’m a believer of each to their own (to some degree), I don’t think we can expect viral social media statuses to have a lasting impact unless they are accompanied by an effort to understand the larger social context. In this case, that context is patriarchy.

A commitment to gender rights should be all encompassing. As my colleague Aishwarya Adhikari points out, “many of those posting #MeToo and standing in solidarity now have been markedly silent on and even oblivious to issues of gender discrimination and oppression in the past and present. While these people are jumping on the bandwagon because of the hashtag that's gone viral, at present, they have absolutely refrained from taking positions before (in fact, often engaging in victim blaming and shaming).”

This doesn’t apply to everyone of course, but there seems to be a distancing from the larger context as often happens in social media trends, and this disjunction is hard to support.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that #MeToo isn’t enough … and it shouldn’t be selective.

In addition to supporting those who post #MeToo, shifting the blame onto perpetrators and starting a desperately needed conversation — we have to ask those who are choosing not to look at the larger context to critically engage with the culture that condones and perpetuates #MeToo in the first place.