I have long been a fan of John Pilger’s work – it is well-researched, honest and powerful without being sensational. There is a dignity to his prose that I very much admire. In a lecture he gave at Columbia University, Pilger spoke of ‘censorship by omission’. In that lecture, Pilger pointed to the terrible omissions of Western culpability in the wars of South-East Asia and Central America,

As a journalist for more than 40 years, I have tried to understand how this works. In the aftermath of the US war in Vietnam, which I reported, the policy in Washington was revenge, a word frequently used in private but never publicly. A medieval embargo was imposed on Vietnam and Cambodia; the Thatcher government cut off supplies of milk to the children of Vietnam. This assault on the very fabric of life in two of the world’s most stricken societies was rarely reported; the consequence was mass suffering. It was during this time that I made a series of documentaries about Cambodia. The first, in 1979, Year Zero: the silent death of Cambodia, described the American bombing that had provided a catalyst for the rise of Pol Pot, and showed the shocking human effects of the embargo. Year Zero was broadcast in some 60 countries, but never in the United States.

When I flew to Washington and offered it to the national public broadcaster, PBS, I received a curious reaction. PBS executives were shocked by the film, and spoke admiringly of it, even as they collectively shook their heads. One of them said: “John, we are disturbed that your film says the United States played such a destructive role, so we have decided to call in a journalistic adjudicator.” The term “journalistic adjudicator” was out of Orwell. PBS appointed one Richard Dudman, a reporter on the St Louis Post-Dispatch, and one of the few westerners to have been invited by Pol Pot to visit Cambodia. His dispatches reflected none of the savagery then enveloping that country; he even praised his hosts. Not surprisingly, he gave my film the thumbs-down. One of the PBS executives confided to me: “These are difficult days under Ronald Reagan. Your film would have given us problems.”

Vietnam remains the unspoken blot on the conscience of the United States. Pilger reported from Vietnam, bringing out the war crime that was the American war on Vietnam.

Pilger made five important films based on his reporting: The Quiet Mutiny (1970), Vietnam: Still America’s War (1974), Do You Remember Vietnam? (1978), Heroes (1980) and Vietnam: the Last Battle (1995). These are essential viewing.

Yesterday, John sent me his reflections on the first episode of Ken Burns’ latest television programme – The Vietnam War. No one is better positioned to assess the documentary than John, who was in Vietnam, reported that war and has made films about the war. When John asked if I’d like to run his story at my website, I jumped on it. So here is John Pilger on Ken Burns’ Vietnam and on the ‘killing of history’.

<<>>

One of the most hyped “events” of American television, The Vietnam War, has started on the PBS network. The directors are Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. Acclaimed for his documentaries on the Civil War, the Great Depression and the history of jazz, Burns says of his Vietnam films, “They will inspire our country to begin to talk and think about the Vietnam war in an entirely new way”.

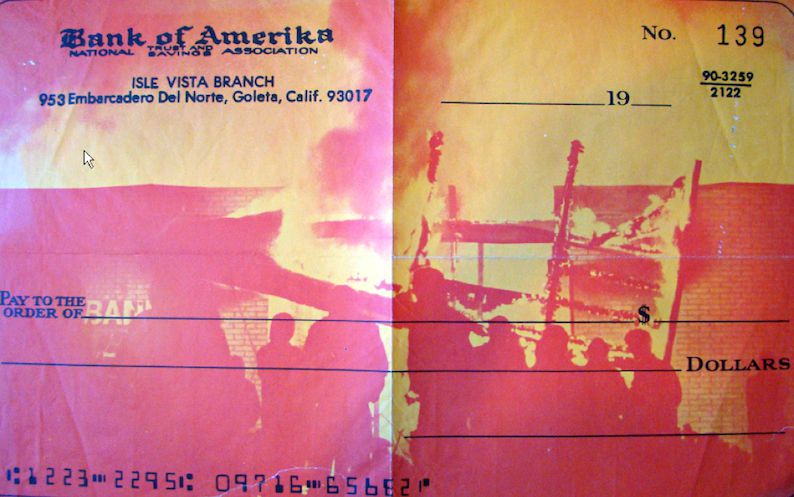

In a society often bereft of historical memory and in thrall to the propaganda of its “exceptionalism”, Burns’ “entirely new” Vietnam war is presented as “epic, historic work”. Its lavish advertising campaign promotes its biggest backer, Bank of America, which in 1971 was burned down by students in Santa Barbara, California, as a symbol of the hated war in Vietnam.

Burns says he is grateful to “the entire Bank of America family” which “has long supported our country’s veterans”. Bank of America was a corporate prop to an invasion that killed perhaps as many as four million Vietnamese and ravaged and poisoned a once bountiful land. More than 58,000 American soldiers were killed, and around the same number are estimated to have taken their own lives.

I watched the first episode in New York. It leaves you in no doubt of its intentions right from the start. The narrator says the war “was begun in good faith by decent people out of fateful misunderstandings, American over-confidence and Cold War misunderstandings”.

The dishonesty of this statement is not surprising. The cynical fabrication of “false flags” that led to the invasion of Vietnam is a matter of record ? the Gulf of Tonkin “incident” in 1964, which Burns promotes as true, was just one. The lies litter a multitude of official documents, notably the Pentagon Papers, which the great whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg released in 1971.

There was no good faith. The faith was rotten and cancerous. For me? as it must be for many Americans — it is difficult to watch the film’s jumble of “red peril” maps, unexplained interviewees, ineptly cut archive and maudlin American battlefield sequences.

In the series’ press release in Britain — the BBC will show it — there is no mention of Vietnamese dead, only Americans. “We are all searching for some meaning in this terrible tragedy,” Novick is quoted as saying. How very post-modern.

All this will be familiar to those who have observed how the American media and popular culture behemoth has revised and served up the great crime of the second half of the twentieth century: from The Green Berets and The Deer Hunter to Rambo and, in so doing, has legitimised subsequent wars of aggression. The revisionism never stops and the blood never dries. The invader is pitied and purged of guilt, while “searching for some meaning in this terrible tragedy”. Cue Bob Dylan: “Oh, where have you been, my blue-eyed son?”

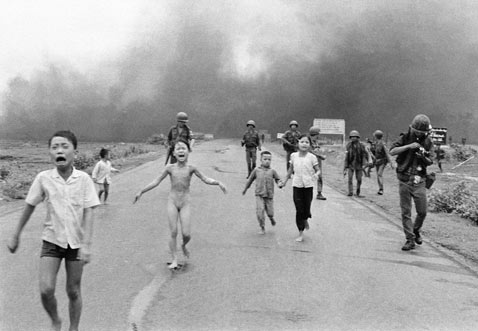

I thought about the “decency” and “good faith” when recalling my own first experiences as a young reporter in Vietnam: watching hypnotically as the skin fell off Napalmed peasant children like old parchment and the ladders of bombs that left trees petrified and festooned with human flesh. General William Westmoreland, the American commander, referred to people as “termites”.

In the early 1970s, I went to Quang Ngai province, where in the village of My Lai, between 347 and 500 men, women and infants were murdered by American troops (Burns prefers “killings”). At the time, this was presented as an aberration: an “American tragedy” (Newsweek ). In this one province, it was estimated that 50,000 people had been slaughtered during the era of American “free fire zones”. Mass homicide. This was not news.

To the north, in Quang Tri province, more bombs were dropped than in all of Germany during the Second World War. Since 1975, unexploded ordnance has caused more than 40,000 deaths in mostly “South Vietnam”, the country America claimed to “save” and, with France, conceived as a singularly imperial ruse.

The “meaning” of the Vietnam war is no different from the meaning of the genocidal campaign against the Native Americans, the colonial massacres in the Philippines, the atomic bombings of Japan, the leveling of every city in North Korea. The aim was described by Colonel Edward Lansdale, the famous CIA man on whom Graham Greene based his central character in The Quiet American.

Quoting Robert Taber’s The War of the Flea, Lansdale said, “There is only one mean of defeating an insurgent people who will not surrender, and that is extermination. There is only one way to control a territory that harbors resistance, and that is to turn it into a desert.”

Nothing has changed. When Donald Trump addressed the United Nations on 19 September? a body established to spare humanity the “scourge of war” ? he declared he was “ready, willing and able” to “totally destroy” North Korea and its 25 million people. His audience gasped, but Trump’s language was not unusual.

His rival for the presidency, Hillary Clinton, had boasted she was prepared to “totally obliterate” Iran, a nation of more than 80 million people. This is the American Way; only the euphemisms are missing now.

Returning to the US, I am struck by the silence and the absence of an opposition ? on the streets, in journalism and the arts, as if dissent once tolerated in the “mainstream” has regressed to a dissidence: a metaphoric underground.

There is plenty of sound and fury at Trump the odious one, the “fascist”, but almost none at Trump the symptom and caricature of an enduring system of conquest and extremism.

Where are the ghosts of the great anti-war demonstrations that took over Washington in the 1970s? Where is the equivalent of the Freeze Movement that filled the streets of Manhattan in the 1980s, demanding that President Reagan withdraw battlefield nuclear weapons from Europe?

The sheer energy and moral persistence of these great movements largely succeeded; by 1987 Reagan had negotiated with Mikhail Gorbachev an Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) that effectively ended the Cold War.

Today, according to secret Nato documents obtained by the German newspaper, Suddeutsche Zetung, this vital treaty is likely to be abandoned as “nuclear targeting planning is increased”. The German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel has warned against “repeating the worst mistakes of the Cold War … All the good treaties on disarmament and arms control from Gorbachev and Reagan are in acute peril. Europe has threatened again with becoming a military training ground for nuclear weapons. We must raise our voice against this.”

But not in America. The thousands who turned out for Senator Bernie Sanders’ “revolution” in last year’s presidential campaign are collectively mute on these dangers. That most of America’s violence across the world has been perpetrated not by Republicans, or mutants like Trump, but by liberal Democrats, remains a taboo.

Barack Obama provided the apotheosis, with seven simultaneous wars, a presidential record, including the destruction of Libya as a modern state. Obama’s overthrow of Ukraine’s elected government has had the desired effect: the massing of American-led Nato forces on Russia’s western borderland through which the Nazis invaded in 1941.

Obama’s “pivot to Asia” in 2011 signaled the transfer of the majority of America’s naval and air forces to Asia and the Pacific for no purpose other than to confront and provoke China. The Nobel Peace Laureate’s worldwide campaign of assassinations is arguably the most extensive campaign of terrorism since 9/11.

What is known in the US as “the left” has effectively allied with the darkest recesses of institutional power, notably the Pentagon and the CIA, to see off a peace deal between Trump and Vladimir Putin and to reinstate Russia as an enemy, on the basis of no evidence of its alleged interference in the 2016 presidential election.

The true scandal is the insidious assumption of power by sinister war-making vested interests for which no American voted. The rapid ascendancy of the Pentagon and the surveillance agencies under Obama represented a historic shift of power in Washington. Daniel Ellsberg rightly called it a coup. The three generals running Trump are its witness.

All of this fails to penetrate those “liberal brains pickled in the formaldehyde of identity politics”, as Luciana Bohne noted memorably. Commodified and market-tested, “diversity” is the new liberal brand, not the class people serve regardless of their gender and skin color: not the responsibility of all to stop a barbaric war to end all wars.

“How did it fucking come to this?” says Michael Moore in his Broadway show, Terms of My Surrender, a vaudeville for the disaffected set against a backdrop of Trump as Big Brother.

I admired Moore’s film, Roger & Me, about the economic and social devastation of his hometown of Flint, Michigan, and Sicko, his investigation into the corruption of healthcare in America.

The night I saw his show, his happy-clappy audience cheered his reassurance that “we are the majority!” and calls to “impeach Trump, a liar and a fascist!” His message seemed to be that had you held your nose and voted for Hillary Clinton, life would be predictable again.

He may be right. Instead of merely abusing the world, as Trump does, the Great Obliterator might have attacked Iran and lobbed missiles at Putin, whom she likened to Hitler: a particular profanity given the 27 million Russians who died in Hitler’s invasion.

“Listen up,” said Moore, “putting aside what our governments do, Americans are really loved by the world!”

There was a silence.