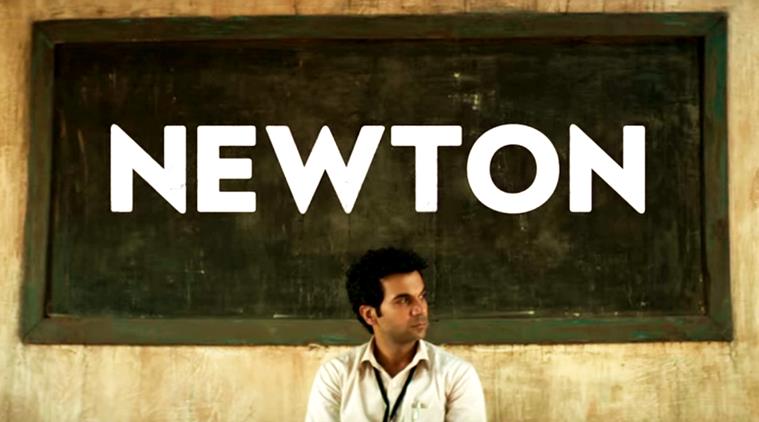

Directed by Amit V. Masurkar, the recently released Newton has joined the ranks of those few films which have been commercially successful without being a Bollywood “masala” entertainer. Within this very sparse community of successful and politically charged films however, Newton stands out. It does exactly what earlier in the film a senior officer advises Newton to do. Newton is told that he is not doing the country any favours by being an honest and dedicated officer (even though that makes him an admittedly rare breed within the gamut of Indian bureaucracy). He is merely doing what is expected of him and should lose his attitude. In the recent spawning of films-with-a-message, Newton is refreshingly unselfconscious about its political agendas. This is no wonder as the film very pointedly refuses to take sides.

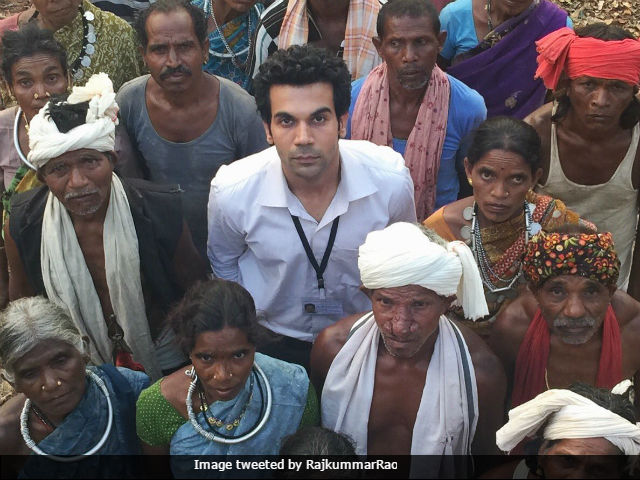

Sent into the inner terrains of Naxalite conflict-ridden areas in Chattisgarh, Newton is avowedly an idealist. Newton is the presiding officer for the polling booth to be set up near Dandakaranya in Chattisgarh, and his team consists of wizened Loknath, the young and mostly-sleeping Shambhu and the local officer Malko. They are accompanied by army personnel, led by Atma Singh. Atma Singh tries to bully Newton, beginning by trying to prevent the election officers from even reaching the stipulated voting booth. Faced with the ignorance and complete alienation of the locals from the voting process, it takes all of Newton’s idealism and faith in democracy to keep going. He is chided by both Atma Singh and Loknath, with a disheartened yet practical Malko being his only accomplice. There are numerous humorous interludes, from the senior police officer who incorrigibly flirts with the foreign media reporter, to the officer-turned-writer Loknath who writes zombie-stories. These instances complement the black comedy of the film and prevent it from becoming somber or tragic.

Newton seamlessly incorporates comments on various issues, for instance, Loknath's callous assertion that the invasion of capitalism (through TV commercials) would “solve” the Naxalites' problems; or Newton’s rejection of a minor for his wife. However, it does so without launching into chest-thumping diatribes and melodrama (remember Toilet: Ek Prem Katha). Newton makes no bones about being an entertainer. Moreover, what makes Newton likeable is that it does not try to impart any lessons to its audience. It merely tries to show the fallacy of democracy in India.

Jnanpith award winning Odiya writer Gopinath Mohanty had written about the Paraja tribe’s complete incomprehension of the relevance of the “Government” of India’s laws to their lives in his 1945 novel Paraja. It has been sixty years since Independence and the “Government” has since changed hands. And yet, the tribal people still remain under coercive rule of their own government. That the scenes from Newton can so uncannily mirror the reality depicted in Paraja indicates the still incomplete (failed?) project of “democracy” in this country. The film does not make a hero out of its protagonist, we still see an idealistic yet sobered Newton by the end of the film. Neither does the film make a villain out of Atma Singh, whom we see in a pitiable light in his familial space. Newton is a mature film which does not try to hammer down messages into its audience’s head. Perhaps this is the very reason that it has found a sympathetic and appreciative audience to hear for what it has to say.

Also by Dipannita Ghosh:

Hindutva Brigade Attacks Jawed Habib’s Durga Ad

McOnam Sadhya: Tinkering with Tradition

The Cultural Implications of Privacy in India

All for a Toilet: Propaganda or Social Reality?

#AintNoCinderella: Online Campaign Against Misogyny