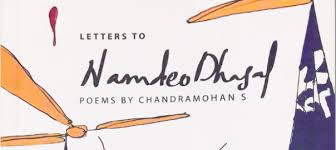

Even as I started reading Chandramohan’s Letters to Namdeo Dhasal, a predicament challenged me: did I have any legitimacy to write about this book?

Chandramohan’s poetry is like a gunshot rudely interrupting English poetry in India. It’s a howl, not only of the poet, not only for our contemporary times, but for all times. Chandramohan’s insertion into Indian literature, especially in English, is a self-conscious intervention. No matter how much I appreciate it, there would be aspects of his poetry — experiences and emotions, rather than technique — to which I would have no access, being a caste Hindu. Yet, the power of the book was so enormous and so immediate that I could not not write about it.

While the book comprises letters to Dhasal, the godfather of 20th century dalit movements in literature, there is also a letter — albeit imaginary — from the poet to a younger one:

In your poems

Do not set your rhyme and meter

With the drum beats of populism(“Namdeo Dhasal’s Letter to a Young Poet”)

Unlike Rainer Maria Rilke’s 10 epistles to Franz Xaver Kappus, written in the first decade of the last century, Dhasal never prescribed any aesthetic or moral philosophy. The advice he provided through his poetry was of subaltern defiance, of violence: “Stay tipsy day and night, / stay tight round the clock / Cuss at one and all; … /Man, you should keep handy a Rampuri knife” (Dhasal, “Man You Should Explode”, Golpitha, translation: Dilip Chitre). Chandramohan’s poem is his own manifesto, his own morals. Its aesthetics is a product of a blacksmith; and it has a postscript: “Do not charge fees to read poems on hunger.”

This is a rejection of the commerce-minded poetry as well as the self-congratulatory activism in wide currency now. Chandramohan rejects both in other poems. In “The Muse in the Market Place”, he writes:

The poem was not conceived with translation in mind

Will never let itself be adopted

Or exported to worldwide markets

The uncompromising attitude continues in “NOTA”:

NOTA

Is the sweat of the sweeper

who cleans the ashes of the effigies

burnt after every Jantar Mantar protest

This is the hallmark of Chandramohan’s poetry — honesty, courage, and the conviction to not compromise under any condition. Consequently, almost every poem in this collection — Chandramohan’s second after Warscape Verses (Authorpress, 2014) — burns with anger, outrage, and a desire for rebellion.

Yet, nowhere is this outrage self-righteous or self-congratulatory; in fact, in a number of poems, it is diluted by a generous dollop of humour. For instance, in the poem “Caste in a Local Train”, he describes a castiest fellow passenger as a Pakistani fast bowler:

Caste in a local train can be deceptive

like the soul

of a Pakistani fast bowler camouflaged

in a three piece suit

and an Anglicised accent.

The only purpose of this passenger is to somehow squeeze out his interlocutor’s caste. Chandramohan describes this interrogation in terms of a duel between a fast bowler and a batsman:

He tries assessing me with an inswinger first

“What is your full name?”Then he tries an outswinger that seams a lot

“And what is your father’s name?”By this time, he loses his patience

And tries a direct Yorker

“What is your caste?”

Observe the enjambments, the division of stanzas that add pace to the narrative; one can almost hear the balls whizzing past the outer edge of the bat. In the pauses between the stanzas, one might imagine the bowler walking back to his run-up — or rather, in this case, the interrogator thinking up a more pointed, and offensive, question to extract information about the hapless victim’s caste.

But the line breaks are also an uncanny reminder of the escalating violence in the questions, which are in any case illegal. One is reminded of the lynching of 15-year-old Junaid Khan in June this year, after an altercation over train seats spiralled out of control. According to some reports, his malefactors stabbed and killed him, after alleging he was carrying beef — adding to the alarmingly long list of attacks on Muslims and Dalits by cow vigilante groups. Chandramohan grapples with it in his powerful “Beef Poem”:

The harvest of my poems will be winnowed.

If done dexterously,

The lighter shallow poems blow away in the wind

While the heavier, meaty poems fall back onto the tray,

To become the fire in my belly

Like beef.

This poem had earned the poet a usual quiver full of online hatred, but it needs no defence whatsoever. In fact, the fire in his belly, whether fuelled by beef or something else, is evident in every enflamed poem of this collection.

In the first of his letters, Rilke writes: “Nothing touches a work of art so little as words of criticism”. What it can attempt to do, however, is illuminate aspects of the work it considers that are hidden in silences, voluntary or enforced. Chandramohan’s poetry conceals as much as it reveals. Such a concealment is essentially a political stance to deny access to state surveillance — another pressing theme of his book. In this critical play of light and shadow lies his art. To a careful reader, this is not only a source of delight but also of enlightenment.