Tara Books is a collective of writers, artists and designers that publishes illustrated books for children and adults. Their visual books span a range of genres: children’s literature, social and art pedagogy, popular culture, photography, and art. Tara Books is “committed to returning the senses back to the physical book in an age busy writing its obituary.” They aim to do this through experiments in content, design and production; by engaging with the rich diversity of Indian folk and tribal art; and by balancing accessibility with “a genuine connection with difference”.

You emphasise experimentation in content, design and production. Could you give us some examples?

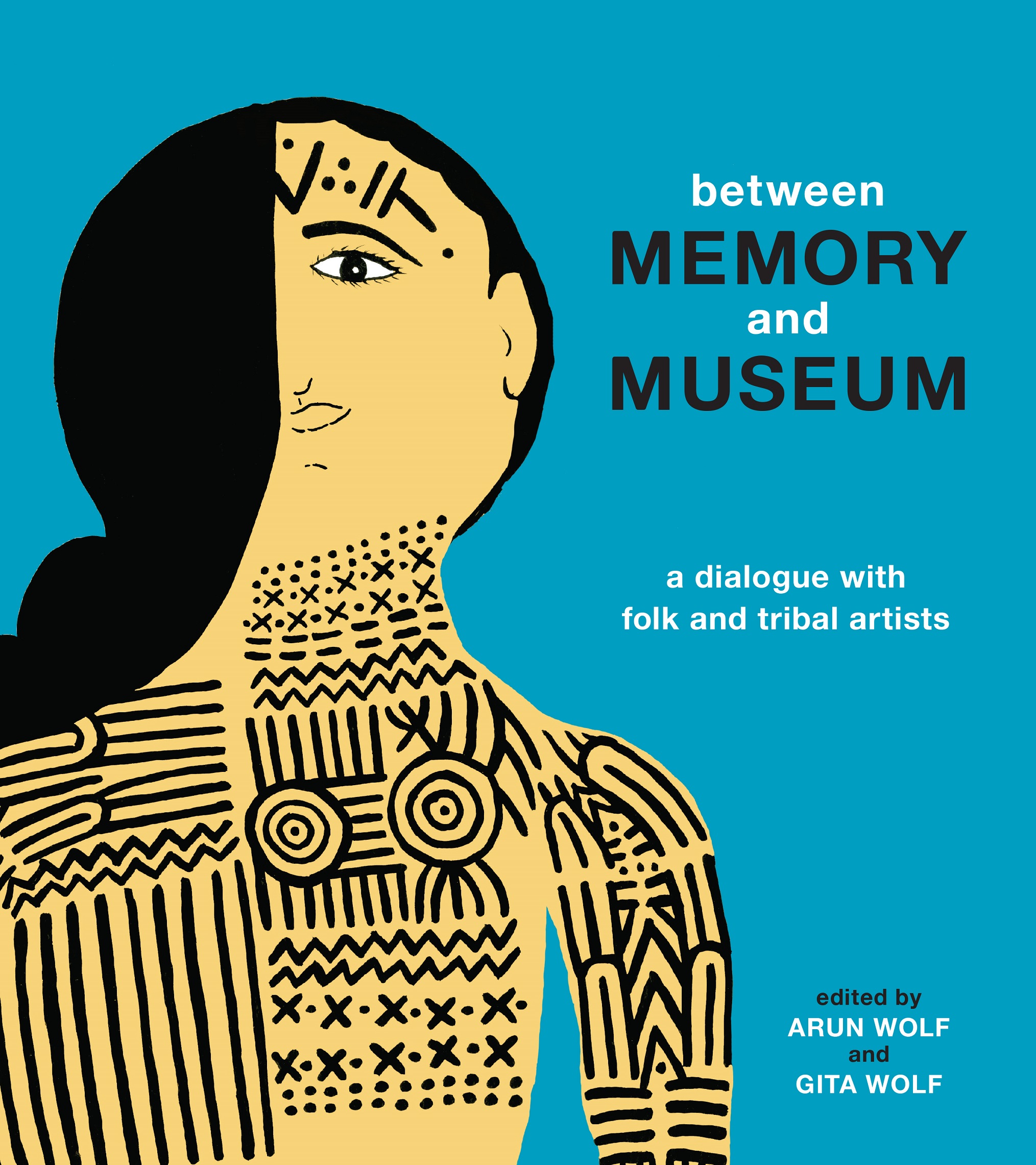

The best example of experimentation with content is our book, Between Memory and Museum: A Dialogue with Folk and Tribal Artists.

This book is based on a ten day long workshop that we did at Manav Sangaralaya, Bhopal several years ago (in 2010), in which we engaged artists from diverse indigenous art traditions in conversations about tradition, memory, the importance or otherwise of the museum in preserving heritage, what lives in museum collections, what is absent, and most of all, about how artists conceive the museum. In the event, artists drew their own visions of the museum, and spoke to us about what had inspired their art. Based on what we had gathered at the workshop we came up with a book that comprises three narrative levels: the art; the artist’s observations on museums, tradition, memory; and our observations that anchor artists’ responses within wider debates on these matters.

The book comprises art and argument, so to speak, and is designed to let the reader linger on the page, take in the images, words, and mull over arguments that are both startling and reflective.

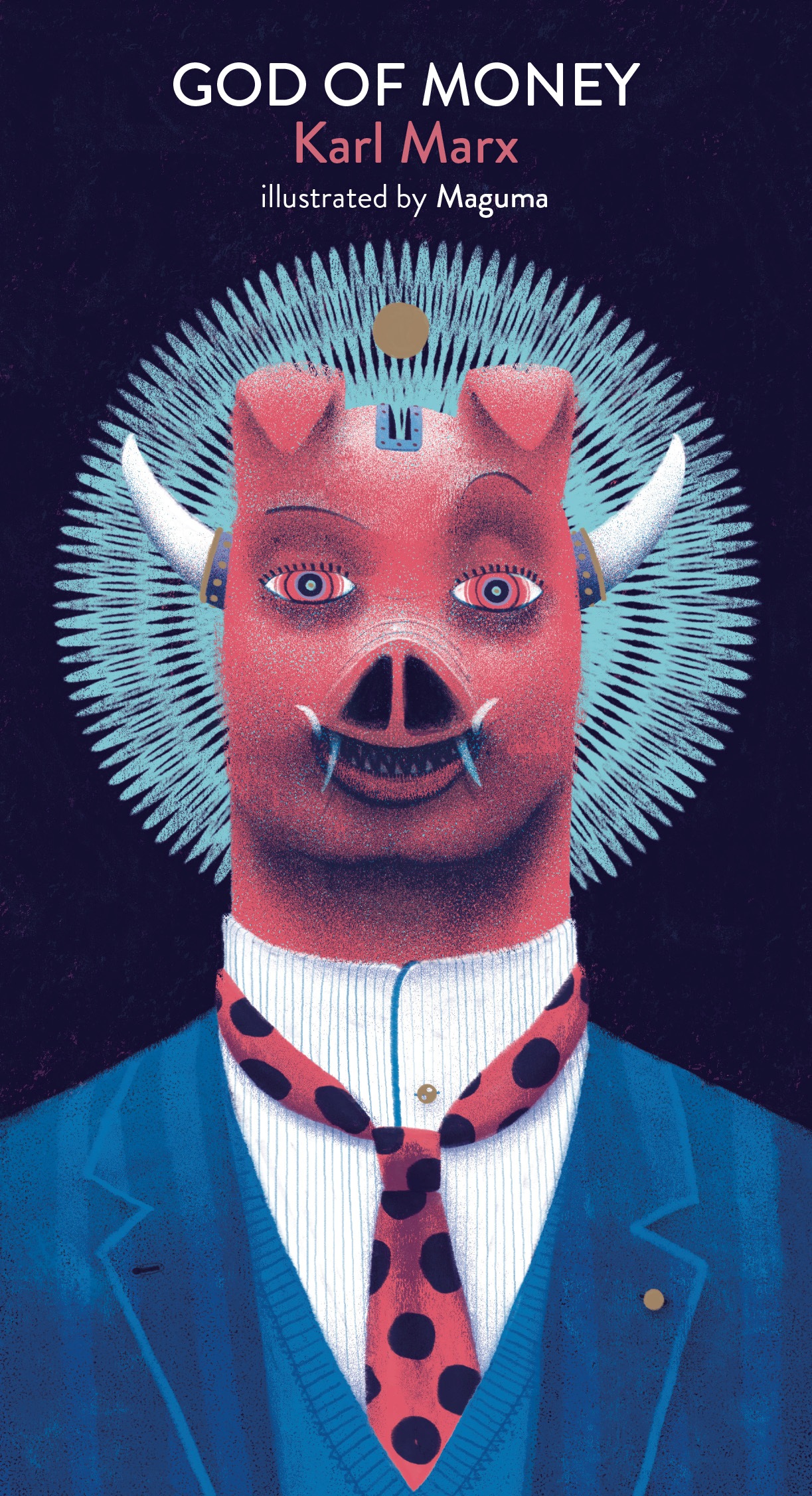

As for design, for us, the designer is as much an author of our books, as is the author and artist. We see the designer as playing both a curatorial as well as editorial role – in the manner she arranges art, text and the page, and sets the conditions for the book’s production. I would like to draw your attention to two books that we have done recently. One is Twins, an art activity book, and the other, God of Money, where the artist played designer as well.

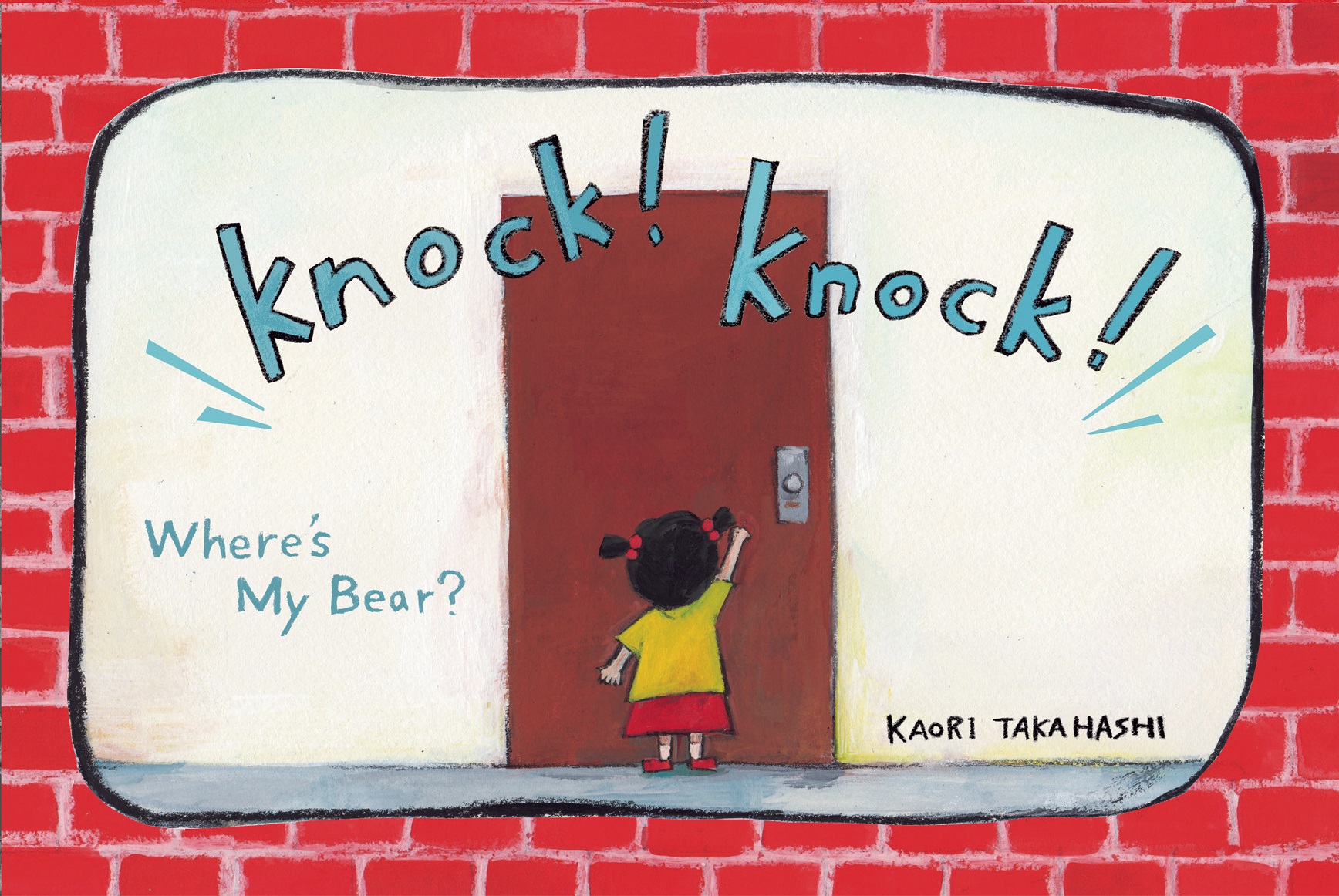

Production, for us, is closely linked to content and design, and we are particular about how the form of the book reflects its content, both in terms of what it adds to content, as well as how it expresses it. One of the more challenging productions in recent times has been the children’s book, Knock! Knock! – which opens out as an apartment block, literally!

Clearly the reading experience is something you consider seriously as you plan your books. What, to you, is the ideal reading experience?

We are focused on the reading experience in two ways: one, in the content that we chose to publish, bringing to the fore voices and artistic expressions that push us to literally ‘see’ the world differently. We are committed to enable readers to ‘picture words’ as well as ‘read pictures’. So, our books are actually exercises in subtle visual communication. In a world obsessed with the fast moving image, where the ability to manipulate seems to be infinite, we suggest that images, as much as words, are integral expressions of meanings we value, whether these have to do with human greed, affection or its absence for the non-human world, and simply for the many ways in which we express a capacity to play, argue, wrestle with the worlds around us.

Thus, the ideal reading experience for us is what allows the reader to linger and return to the pages that interests her. It is what it has been for several centuries now: a quiet communion with the world of the book, with its mix of words and images, a world that continues to fascinate, beguile, frighten, and startle us.

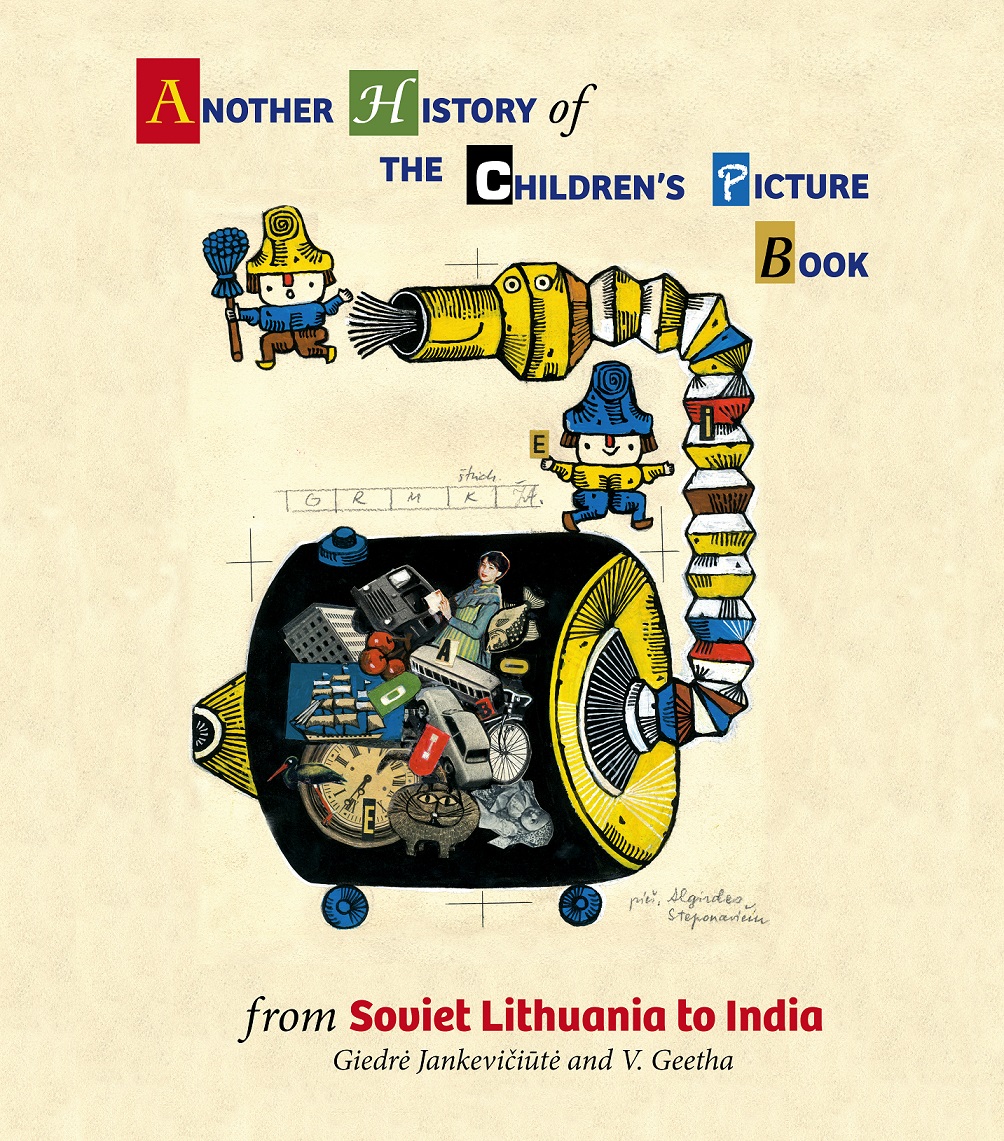

If you pick up two very different books from our list, The Night Life of Trees, which is image-intensive, and Another History of the Children’s Picturebook, which is a fair combination of text and image, you’ll get a sense of what we understand to be the ideal reading experience.

The way you use ‘Indian’, ‘folk’ forms to narrate classics, or even contemporary books is particularly interesting to me. (I don’t want to use the term ‘traditional’ Indian art forms, for clearly you see the ‘traditional’ as ‘contemporary’.) What is the importance of retelling for Tara Books?

We understand tradition to be a relationship to the past, rather than as something that conveys the past, or stands in for it. We are all in media res, so to speak, in the middle of cultural processes that have existed for long before us.

Working with Indian folk and tribal artists (much as we are uneasy with these terms, we continue to use them, since they have come to stay), we have learned to re-look the world through their eyes. Tribal artists are anchored in ways of seeing and doing that retain the impress of past times, but they are also keenly aware of the present, and so look to renew their relationship to the past — that is, when they don’t have to ‘perform’ being tribal.

In our conversations with them, we have suggested that the book form, as distinct from the gallery and museum, might be a space that allows for reflective art. So, for us, tradition is not important in itself, but in how it links us to what has gone before and what will come after. How we do this linking, what we chose to link — artists do this differently, and we as publishers do it in ways that answers our contemporary concerns with the good, just and beautiful life.

There is an emphasis on tactility, on a certain joy in touching, feeling books. Is this a conscious reaction to the upsurge in digital, non-physical books?

Not in so many words. Since we consider printing, the choice of paper and the way the page looks and communicates as enhancing reading, we have looked to experiment with form, with printing processes. Our handmade books emerged out of this understanding of the book form. To us, it is a valuable cultural object, and we think that its form, as we know it, ought to be constantly renewed. The digital present is one moment in the long and complex history of human innovation with respect to forms of communication — and it appears a dramatic moment. But it still relies on the book form even if works with other ‘platforms’ as it refers to them.