Rohingyas today are the world’s most persecuted minority. The news, images, videos which are coming from Burma’s Rakhine province are shocking. There are mass killings going on which amount to nothing less than genocide. In these terrible times the Rohingyas have no other option than to leave Burma, just to stay alive. When I talked to Salimullah, he said “the situation today is even worse than how it was in 2012. We were lucky to have left Burma before it started. The people those who are there now, will face nothing else than a horrifying death.” Their experiences in India have been quite positive. Apart from living in an environment of peace, most of the refugees have found a way to sustain economically.

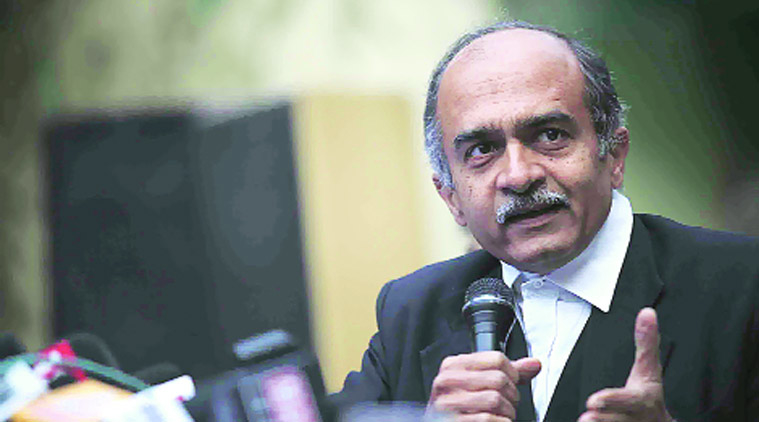

However, the Indian government plans to deport the people living here in various rehabilitation centres. Thankfully beyond all these moral, ethical arguments, lies the legal framework, on which Prashant Bhushan has filed a petition, which might be the only thing that will save the lives of the refugees.

What is the petition by Prashant Bhushan all about?

A writ petition under Article 32 of the Constitution of India has been filed, to secure and protect, the right against deportation, of the petitioner refugees in India, in keeping with the Constitutional guarantees under Article 14 and Article 21, read with Article 51(c) of the Constitution of India against arbitrary deportation of Rohingya refugees who have taken refuge in India after escaping their home country Myanmar due to the widespread discrimination, violence and bloodshed against this community in their home country. The petitioners have been registered and recognised by the UNHCR in India in 2016 and have been granted refugee I-cards.

The ‘Non Refoulement’ text, meaning we cannot deport people when they face imminent threat to their lives states:

“No contracting State shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened on account of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” A copy of the Convention relation to the Status of Refugees, 1951.

Though India is not a signatory of ‘UNHCR’ Refugee treaty, still it is applicable to India, as a part of customary international law, which is binding on India.

The Indian Constitution accords refugees some degree of constitutional protection while they are in India. The following constitutional provisions offer a framework for protecting the rights of refugees:

● Article 51 (c) of the Indian Constitution, a Directive Principle of State Policy, requires fostering of respect for international law and treaty obligations in the dealings of organised peoples with one another.

● Article 14, Right to equality states: “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.” This article guarantees to refugees in India, the right to equality before law and equal treatment under the law.

● Article 21, Right to life and liberty: “No person shall be deprived of his life of personal liberty except according to procedure established by law”. In according protection to refugees, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has interpreted these constitutional provisions to extend the protection of the right to equality and the right to life and personal liberty of refugees.

In the light of the constitutional framework and international laws, Prashant Bhushan has built up a very strong case, drawing parallels and taking references from many other cases.

Some of the cases he has referred to can be seen in the following excerpt from the petition:

“That the Supreme Court in its landmark judgement on the right to privacy dated 24th August 2017, in, Justice K.S. Puttaswamy (Retd) and Anr. v. UOI and Ors WP (C ) No. 494/2012, has categorically stated, “Constitutional provisions must be read and interpreted in a manner which would enhance their conformity with the global human rights regime. India is a responsible member of the international community and the Court must adopt an interpretation which abides by the international commitments made by the country particularly where its constitutional and statutory mandates indicate no deviation.”

Another excerpt from the petition:

“That In the National Human Rights Commission v. State of Arunachal Pradesh (1996) 1 SCC 742, the Supreme Court , states “Our Constitution confers certain rights on every human being and certain other rights on citizens. Every person is entitled to equality before the law and equal protection of the laws. So also, no person can be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedureestablished by law. Thus, the State is bound to protect the life and liberty of every human being, be he a citizen or otherwise”

Though India is not a signatory of UNHCR, as Kiren Rijiju has repeatedly stressed, we have a judgement which says the opposite.

“The Delhi High Court in Dongh Lian Kham v. Union of India, 226(2016) DLT 208, states, “The principle of “non-refoulement”, which prohibits expulsion of a refugee, who apprehends threat in his native country on account of his race, religion and political opinion, is required to be taken as part of the guarantee under Article 21 of the Constitution of India, as “non-refoulement” affects/protects the life and liberty of a human being, irrespective of his nationality.”

The demands of the petition are following:

- To issue an appropriate writ, order or direction, directing the Respondents not to deport the petitioners and other members of the Rohingya community who are presently in India.

- To issue appropriate writ or order directing the respondents to provide the petitioners and other members of the Rohingya community in India, such basic amenities to ensure that they can live in human conditions as required by International law in treatment of refugees.

- To pass such other order as this Hon’ble Court may deem fit and proper in the interest of equity, justice and conscience.

I am glad there are people like Prashant Bhushan who are ready to stand up and fight for people who have no country of their own. It is sad that there has to be a legal case to uphold the humanity of a nation, but also great that there are those who will take it up time and again.