“Sirajuddin was sitting. Four people walked past him, carrying someone.

When he inquired, he learnt that they had found a girl lying unconscious near the railway tracks and had brought her to the camp. He followed them.

They handed the girl over to the hospital. Sirajuddin stood leaning against a pole outside the hospital for sometime. Then he slowly walked into the hospital.

There was no one in the room. Only the body of a girl lay on the stretcher. He walked up closer to the girl. Someone suddenly switched on the lights.

He saw a big mole on the girl’s face and screamed, “Sakina!”

The doctor, who had switched on the lights, asked, “What’s the matter?”

He could barely whisper, “I am… I am her father.” The doctor turned towards the girl and took her pulse. Then he said, “Open the window.” The girl on the stretcher stirred a little.

She moved her hand painfully towards the cord holding up her salwar.

Slowly, she pulled her salwar down.

Her old father shouted with joy, “She is alive. My daughter is alive.”

The doctor broke into a cold sweat.”

Pulling her salwar cord for the next round of gangrape. Sakina.

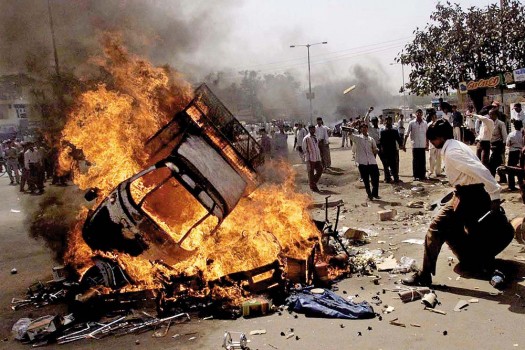

No, this is not the testimony of a Gujarat 2002 survivor from Naroda Patiya.

Yes, in 2002, many fathers and mothers, brothers and uncles found their gangraped daughters/ sisters/ wives abandoned in the fields, or in crowded lanes full of charred bodies and burnt down homes, and sometimes – if they were lucky – inside a hospital still alive, like Sakina.

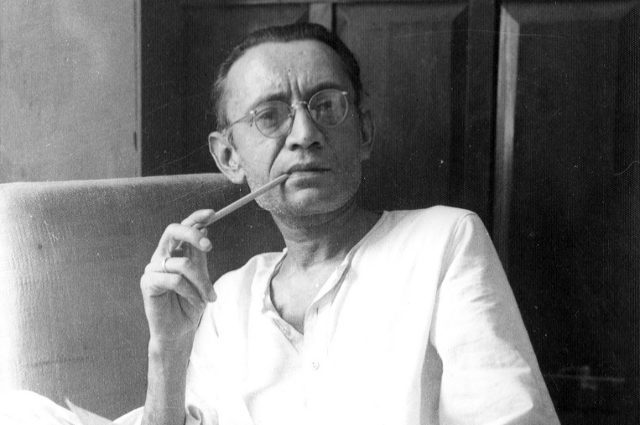

This is an excerpt from Manto’s ‘Khol Do’, written in the aftermath of the horrific violence unleashed during the partition of India by bloodthirsty mobs from both sides of the hurriedly-created border.

Manto: Among my earliest influences

Though my father, a minor literary figure in the early years of the Nai Kahanimovement, stopped writing by the late 60s, he had a library full of anything significant written in Hindi. I started reading literary stories as a 7-year old, devouring mainstream magazines like Dharmyug, Saptahik Hindustan, Navneetetc and several minor literary journals like Vinod etc. Soon, I discovered Premchand, followed by Yashpal, Krishna Sobti, Bhisham Sahni and many others.

I found Manto when I was 10 years old. By 14, I had re-read many of Manto’s stories, understanding more of the nuances and layers with each subsequent reading. I had grown up with stories and anecdotes about the tremendous upheaval caused by the Partition in my maternal grandmother’s family; from being ‘landed gentry’ in Pakistan, they turned paupers overnight in 1947, barely escaping to India in time.

I was privy to the incidental narratives of grief, loss, tragedy and mayhem as I was the oldest grandchild, often on chaperone duty, escorting my grandmother to sundry reunions within the ‘partition community’. Manto gave me a broader understanding of the fragmented narratives from within my own family and from the many others I met and heard during such meetings.

I still recall the first time I read the short sketch ‘Mishtake’ – it traumatized my young mind to imagine such a mob, but in it I found echoes of the stories I had been hearing.

“Ripping the belly cleanly, the knife moved in a straight line down the midriff, in the process slashing the cord which held the man’s pyjamas in place. The man with the knife took one look and exclaimed regretfully, ‘Oh no!… Mishtake!”

While still in my early teens, I learnt from Manto that the universe wasn’t purely black-and-white. That it contained within it ambiguity, ambivalence and contradictions. That a moment could transform a good person into the vilest monster, or lead to noble, selfless deeds by a ‘bad person’ – a pimp, prostitute, conman or a dishonourable neighbour. That violence didn’t end or vanish with the return of ‘normalcy’ – that those touched by it got affected and transformed, even the perpetrators. (This, in fact, forms a significant part of my upcoming work ‘Final Solution Revisited’, in which I speak to several ‘footsoldiers’ from the mobs.)

I still re-read Manto, every couple of years – he continues to guide and inspire me. How I wish his words didn’t ring true nearly 70 years later!

“Blowing on the blood-cot forming on his mustache, Eesher Singh said, “The house I attacked had seven people in it. I killed six of them, with the same dagger you stabbed me with. There was a beautiful girl in the house. I took her with me.”

Kalwant Kaur was listening intently. Eesher Singh once more tried to blow the blood off his mustache. “Kalwant darling, I cannot tell you what a beautiful girl she was. I would’ve killed her too. But I said to myself, no, Eesher Singh, you enjoy Kalwant Kaur every day. Taste a different fruit.”

“Oh” was the only word out of Kalwant Kaur’s mouth.

“I put her on my shoulder and got out. On the way… what was I saying… oh, yes… on the way, near the river, I lay her down by the bushes. First I thought deal the cards. But then I decided not to…” Eesher Singh’s throat was completely dry.”

“Then what happened?” gulped Kalwant Kaur.

“I threw the trump card… but… but…” Eesher Singh’s voice was now a mere whisper.

“Then what happened?” Kalwant Kaur shook him.

Eesher Singh opened his tired and sleepy eyes and looked at Kalwant Kaur whose whole body was trembling. “She was dead, Kalwant, it was a dead body… a cold flesh… please hold my hand.”

Kalwant Kaur put her hand over his. His hand was colder than ice.”

– ‘Thhanda Gosht’

The Spanish philosopher George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Perhaps this is why I haven’t been able to bring myself to move on, to stop chronicling the impact of a cataclysmic event like the 2002 massacre or the Mumbai terror attack or the Malegaon bomb blasts. I’ve also begun to feel that there are too few of us exploring this contemporary reality of ours in art, theatre, literature or cinema (unlike, say, Germany, where the Holocaust formed a part of the discourse not just in the arts but also in school classrooms – rather than sweep the horrific memories away or bury them, they kept the discourse alive).

Each time I decide ‘no-more-documentaries’, I cannot bring myself to abandon the journey I’ve found myself on from 2002 onwards. I even resisted filming in Malegaon for a couple of years, but once it became apparent that no one – not a single film-maker – had filmed in Malegaon and was unlikely to, I felt I had no choice but to document what I considered to be a key moment in Indian polity – the next phase of aggressive assertion of Hindutva, after Babri 1992 and Gujarat 2002.

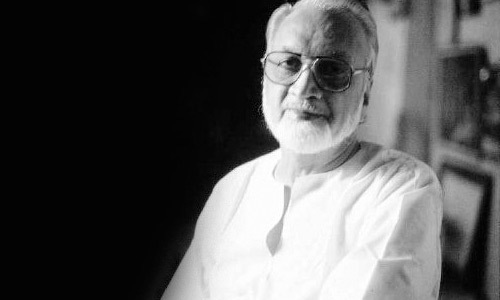

Vijay Tendulkar / Image courtesy: Junoontheatre

Vijay Tendulkar: Another early influence

One of the playwrights I’ve always admired is Vijay Tendulkar; I got exposed to his Marathi plays, through the Sarojini Verma Hindi translations, while in college.

Mrigank Ojha, Amitabh Gupta, I and a bunch of others were so inspired by‘Khamosh, Adalat Jaari Hai’ as first year students that it became the first play we produced, with a lavish budget of nearly one lakh, way back in the 1980s (shamelessly haranguing our college mates at SRCC to solicit ‘brochure-ads’ from their corporate dads). We were very intense and committed, and quite aware of our own limitations. This led us to do something rather unusual for the time – we engaged a senior NSD pro to train and direct us, paying him a then princely sum of Rs 20,000 for the 4 months of daily rehearsals!

I played Ponkshe and must have looked like a comic sight – a reed thin young man wearing an ill-fitting safari suit and smoking a pipe – even though many including Nemichand Jain, the khadoos critic, gave me good reviews! I, however, had my ‘lightbulb moment’ during the 15-20 shows we did – I realised that I was at best going to become a competent actor, never really a very good one. I also found that I loved doing the other stuff – lights, sets and music cueing/ playback etc – my first step in the journey to becoming a ‘director’.

Years later when Tendulkar called me up to express his support and solidarity around the time my film ‘Final Solution’ was banned, he was very amused to find that he was one of the people to blame for all my current travails!

Tendulkar’s explorations of violence fascinated me – I read everything he had written in the period immediately after his Ford Foundation grant to study violence, especially the plays that explored it within a finite universe – the family, community and society. Just reading a Sakharam Binder or Giddhgave me a deeper glimpse and a layered understanding of human behaviour.

Other early influences:

Phaneeshwar Nath Renu‘s short story collection ‘Thhumri’ still lives and breathes inside my head. Renu – dismissed by the Hindiwalas as an “aanchalik” (regional) writer – painted gentle portraits, captured little

moments and evoked within his readers the sense of joy, pain, hurt, anger or desolation his characters were feeling.

Anyone with even a passing level of interest in Indian politics must read Shrilal Shukla’s ‘Raag Darbari’, a timeless classic and brilliant satire written nearly 50 years ago. It is a book a few friends and I return to every couple of years, reading our favourite passages aloud to each other and to their young children! Over the years, I have bought at least 20 copies of the book but often find it missing from my library, as I keep handing it out to anyone who comes home and discusses ‘politics’! No excerpts – go buy the book, read and chuckle through it. And then pause to think why our current polity resembles the Shivpalganj universe explored so brilliantly in the book.

RSS: An even earlier influence

Among the many fringe benefits of a North Indian childhood was my early exposure to chaddhi-uncles – the middle aged men in flaring khaki shorts conducting their drills in the same public park where we were trying our best to emulate Andy Roberts and Lilee-Thompson. Quite naturally, the local RSS‘shakha’ demographics didn’t include any young children, as cricket was far more interesting to us than their pet lectures on Bharat Mata and Gau Mata. Their worldview and narratives of history seemed strange, especially as we were already being exposed to Gandhi, Nehru, Bhagat Singh, Bose, Chandrashekhar Azad and Bismil.

During election times, these chaddhi-uncles went door-to-door campaigning for Jan Sangh, invoking Gau Mata and Bharat Mata and their ‘hinduspeak’ (the overbreeding Muslim working overtime to ensure Hindus became a minority very soon, Kashmir and Akhand Bharat etc). For us children, this was a special time for no-holds-barred fun and we would march through the lanes shouting our own slogans – “Gali gali mein shor hai, Indira Gandhi chor hai” or“Beedi mein tambhakhu hai, Jan Sangh daku hai” and my then favourite “Gaay hamari mata hai, aur kuchh nahin aata hai, bael hamara baap hai, vote dena paap hai.” The best of our mirth was always reserved for these chaddhi-uncles.

None of us could imagine this loony fringe ever becoming mainstream, voted to power with an absolute majority, emboldened to wreak havoc as vigilante groups…

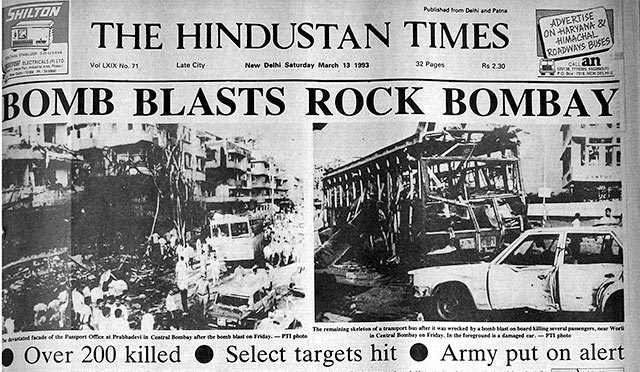

The defining experiences: The 1993 Bombay riots

Bombay, the city I called home for 23 years…

In 1992-93, I ran the Nivara Hakk relief camp in Jogeshwari (East) on a full-time basis for a few months. I lived just a mile away from the so-called trigger point – the Radhabai chawl, next to Jhoola Maidan, where members of the Bane family had been burnt alive. It felt like my own backyard was on fire, so how could I just stay away and not help douse the flames?

I saw the many layers of grief, anger, resignation, and despondency, as well as the many petty, ugly, charming, and irritating facets of everyday politics at the mohalla level. I was taken around to the ‘borders’ and ‘morchas’, terms I was hearing for the first time, referring to the lanes and gutters that separated the two communities’ slum dwellings.

After the 1993 bomb blasts, I remember walking around stunned past the Century Bazaar or the Air India building, looking at the shattered glass, the debris, the damages floors and structures.

The history I had grown up reading without really comprehending in its entirety was replaying itself around me. Manto’s words suddenly came resoundingly alive, all around me, in the very city he wrote of so fondly.

Those weeks and months taught me much about humans and the things they do, the depravities they are capable of, the sudden moments that transform a benign father into a monster, moments that bring out the compassion and the bitterness – a space full of an interwoven web of complexities, ambivalences and ambiguities.

However, through these months, I never filmed anything, not even a still frame! I was far too mired in real life to even attempt to be a dispassionate chronicler. The many layers of understanding I developed here later got reflected in ‘Final Solution’ though.

Delhi 1984:

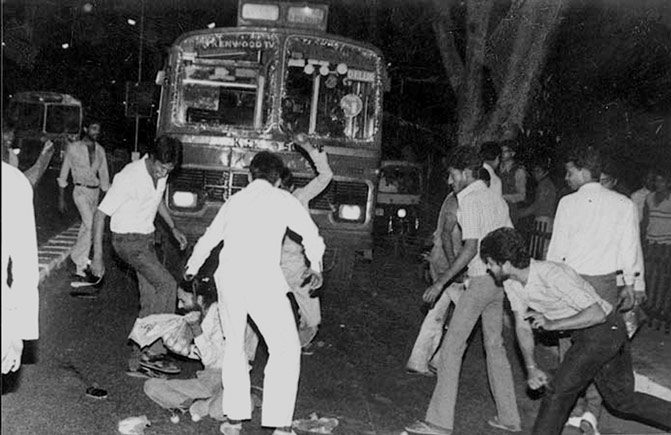

Earlier, while in college, I’d seen the 1984 anti-Sikh carnage first hand.

In Connaught Place, with the looting in full swing, with people from all classes helping themselves to anything they could lay their hands on.

In Paharganj, as it worsened – how helpless I found myself seeing a mob chase a middle-aged Sikh shopkeeper, unable to intervene.

In Trilokpuri, in its deathly silent lanes and in the relief camps in the days and weeks later.

Delhi replayed the horrific violence of 1947 in its streets and its posh localities, even as all of us watched, helpless and stunned.

Later, Babri 92 and Bombay 92-93 opened my eyes in a fuller manner.

Manto’s words rang true and echoed then too. But I had perhaps blindsided myself into believing this was specific to the North Indian psyche, one shaped by the recurring invasions from the Khyber Pass and the horrors of the Partition.

‘Final Solution’: The 2002 Gujarat carnage

Having worked in relief camps in 1984 and 1993, I no longer wanted to volunteer for the immediate ‘red-cross type’ relief (milk, essential supplies, medicines, blankets) or the longer-term work (filing FIRs with local police, affidavit-making, processing compensation claims, getting the relief cheque released and suchlike) in 2002.

I decided to use all my available skills, especially film-making, to make an ‘intervention’ and craft my own plea against hate, bigotry and violence.

It took me almost 6 months to define and understand the why, what and how; I didn’t film at all after an initial trip to Gujarat in March 2002. Finally, it was on Oct 2, Gandhi’s birth anniversary, that I found myself aboard a train hurtling towards Gujarat, on my way to film the Gaurav Yatra (Pride Parade) that CM Modi had embarked on. I nearly gave up on Day One itself, when I realised that his rally was making detours to often halt at the exact site of some of the worst atrocities, a rather macabre celebration. It was a challenge even to scan the faces of the cheering crowds, as I wondered how many of them had been a part of the marauding mobs.

Had I not been ‘detained’ for hours on a dark highway on my first day of filming the Gaurav Yatra “on orders from Saheb” (the Patan Police SP’s words), I probably would’ve given up after a few days of filming. (It was too hard to take – all those stories of human depravity unleashed during the carnage, and the lingering sense of tension and Hindutva aggression).

But, in that moment, surrounded by the cops, with a large mob collecting to have a go at the “suspected Kashmiri terrorists” (the message flashed through the control room to police mobile vans), I felt myself boiling with rage even as I awaited the campaign-in-charge Amit Shah to come and vet me, the ‘noise-maker’ acting tough with the cops. The SP had pleaded his inability to ‘release’ me citing orders from ‘above’ – so it took an Amit Shah to leave a Modi rally and drive a few miles to come and personally check me out on the outskirts of Patan.

All that went through my mind on a loop was – filming is my birthright, the Indian Constitution gives me the right to freedom of expression, how dare anyone stop me?

It was that night that I decided that I’ll make ‘Final Solution’, no matter what. And I released the film 15 months later, 3 months before the 2004 elections to the Indian Parliament.