“In 1947, brothers and sisters, the British left granting India her freedom, granting the Muslims Pakistan, granting special provisions for the scheduled castes and tribes, leaving everything taken care of, brothers and sisters –

Except us, EXCEPT US. The Nepalis of India. During that time, in April of 1947, the Communist party of India demanded a Gorkhasthan, but the request was ignored. We are, labourers on the tea plantations, coolies dragging heavy loads, soldiers. We are Gorkhas. Our loyalty and character has never been in doubt. And have we been rewarded? Can our children learn our language in schools? Have we been given compensation? Are we given respect?

No! They spit on us."

Image Courtesy: Darjeeling times

Image Courtesy: Darjeeling times

This excerpt of a speech from the Booker Prize winning novel “The Inheritance of Loss” by Kiran Desai mirrors the current unrest in Darjeeling led by Bimal Gurung, the leader of Gorkha Janmukti Morcha.

Kiran Desai, who won the Booker Prize (2006) for her novel, portrays the unstable political period in the mountainous region of Kalimpong in the eighties – when Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF), led by Subash Ghising – the Guru of Bimal Gurung, demanded a separate Gorkhaland in Kalimpong and neighbouring Darjeeling.

In a crumbling Scottish mansion named Cho Oyu lives Sai, a seventeen-year-old girl, with her grandfather, a retired civil court Judge. The small family extends to the judge’s beloved dog, Mutt, and his faithful cook. The very first chapter portrays the liberation army of GNLF, made up of young lads, enter Cho Oyu forcefully – ‘in leather jackets from the Kathmandu black market, khaki pants, bandanas – universal guerrilla fashion. They were looking for anything they could find – kukri sickles, axes, kitchen knives, spades, any kind of firearm.’

The situation is also profiled through the character of Gyan who is however, not part of the same class as Sai. He speaks a different language and eats more indigenous food. He is a Nepali, a minority group in India but a majority in Kalimpong. He tutors Sai and is paid a paltry sum for his time and effort by the judge. He tells the story of his great grandfather, his great uncles who were in the British army, “And do you think they got the same pension as the English of equal rank? They fought to death, but did they earn the same salary?”

Image Courtesy:Coffee with a story

Image Courtesy:Coffee with a story

Slowly it dawns on Gyan why he had no money and why no real job came his way, why he couldn’t fly to America and why he was ashamed to let anyone see his home. He and his kin did not enjoy the same rights as the others around him including the Anglo Indians, Bengalis, Marwari businessmen, and even the Lepcha tribals. Destitute Anglo-Indian students in Dr Graham’s Homes were better off than him. They all belonged here lawfully – whereas his identity was questioned all the time.

The novel deals with the quest for individual identity. It is the struggle, for search of one’s root, in a world that has undergone a significant change in the postcolonial era. The conflicting ethno-racial relationship between people who came from different cultural, historical, religious and social background throws up a playfield of unease. For meeting of varied cultures is never harmonious. Often violent, it peters out to a compromise and sometimes subsumes the weaker culture.

Kiran Desai gives a backdrop to the agitation in the book – “When England controlled much of India, they brought in Nepalis to work on the tea plantations, and although colonialism is officially gone, the descendants of these people still live in the border region, but do not have equal rights. During the mid-1980s in the border region of India, including Darjeeling, there were numerous processions, demonstrations, and some violent riots by minority groups who wanted fair treatment.”

GNLF wanted to bring dignity and a sense of belongingness to their people. The biggest insult they often faced was when they registered the utter bewilderment of people who didn’t consider them to be ‘Indian citizens’. Leading a procession through Kalimpong, Gyan’s fellow agitators proclaimed loudly, “This is where we were born, where our parents were born, where our grandparents were born. We will defend our own homeland, we will run our own affairs in our own language. If necessary we will wash our bloody kukris in the mother waters of the Teesta, jai Gorkha.”

Image Courtesy: Coffee with a story

Image Courtesy: Coffee with a story

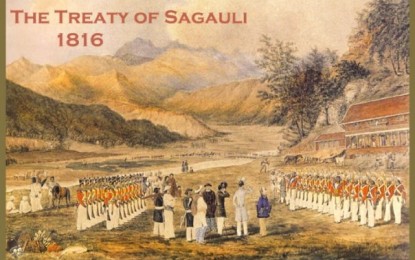

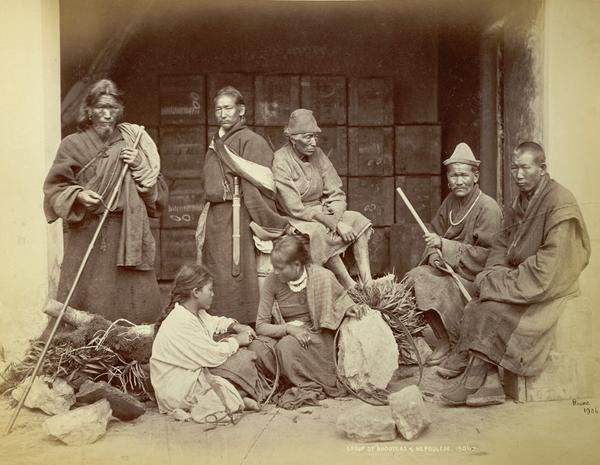

Conversations between Anglo-Indian residents in the novel bring in further details of the history of Gorkhas. Around the 1800s Nepali people left their villages and migrated to the tea plantations of Northern Bengal in search for work. They settled in hamlets bordering remote tea estates of Darjeeling-Kalimpong area. By and by along came the imperial army looking for strong soldiers to fight their wars. They were delighted to discover the Gorkhas – able, courageous, obedient and to top it, loyal to the core. They recruited them in numbers, and the Nepali soldiers fought English wars in World War I and II, besides imperialistic expeditions. They brought innumerable victories to the British and were decorated with honours. A Statue of a Gorkha soldier at Westminister is the testimony of their valour and the part they played in British wars.

Of course many perished on battlefields fighting alien wars and sometimes against their own brothers in Pakistan, India and South East Asia. Still there are a number of Nepali soldiers in the Malaysian, Singaporean armies today. The Indian army also kept its doors open to recruit Nepalis in its cadre. The Gorkha regiment was the pride of the armed forces in India.

When power suppresses, resistance is born in its interstices. Despite the fact that generation of Gorkhas have lived in the Bhutan-Sikkim-West Bengal sector since the 1800, this part of India has been a messy map. First, the Gorkhas were turned out of Assam and Meghalaya. The King of Bhutan made noises against influx of immigrants to his country. The novel further argues, “A great amount of warring, betraying, bartering had occurred: between Nepal, England, Tibet, India, Sikkim, Bhutan; Darjeeling was annexed from Sikkim, Kalimpong plucked from Bhutan.”

The proud Gorkha felt betrayed, “In our own country, the country we fight for, we are treated like slaves. Here we are eighty percent of the population, ninety tea gardens in the district, but is even one Gorkha-owned? Every day the lorries leave bearing away our forests, sold by foreigners to fill the pockets of foreigners. Everyday our stones are carried from the river bed of the Teesta to build their houses and cities. We are labourers working barefoot, in all weather, thin as sticks, as they sit fat in managers’ houses with their fat wives, with their fat bank accounts and their fat children going abroad.” Their fury flamed over, overflowing into the streets, as they looted shops, burnt lorries and burgled rich Anglo-Indian bungalows.

The current situation in Darjeeling is akin to the political and cultural upheaval discussed in the book. History may never repeat itself but it often rhymes and “those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it”.