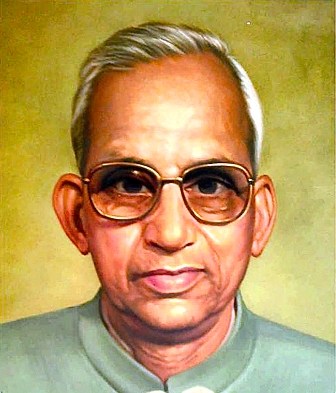

Ramswaroop Verma (22 August 1923 – 19 August 1998) was born into a Kurmi peasant family of Gaurikaran village, Kanpur Dehat, in Uttar Pradesh. His father Vanshgopal and mother Sukhiya wanted that their son to acquire higher education. Verma was a brilliant student. He did his MA from Allahabad University and LLB from Agra University in an era when the institutions of higher learning were virtually out of bounds for the Shudras – though the British rulers were gradually easing restrictions on women and Shudras acquiring education. He studied Urdu, English, Hindi and Sanskrit. After completing his education, Verma had three options before him – joining the administrative service, practising law or serving the Bahujans of India through politics. Verma had cleared the written examination for recruitment to the IAS but even before appearing for the interview, he had decided on the course his life would take. He knew that he could lead a comfortable life by joining the IAS, but as a civil servant, it would not be possible for him to liberate the Bahujan community from its belief in fate, rebirth, superstitions, ritualism and miracles. On 1 June 1968, in Lucknow, he founded the Arjak Sangh for raising social awareness and consciousness. Ramswaroop Verma owed his political consciousness to a speech of Dr Ambedkar at the convention of the workers of Scheduled Castes Federation at Park Town Ground in Madras on 1944. Ambedkar had said, “Go and write on your walls that you want to be the governing community of the country so that you can remember it every time you walk past them. Another speech by Ambedkar at Begum Hazrat Mahal Park, Lucknow, on 25 April 1948, in which he said that the SCs, STs and OBCs would come on one platform; they would be able to take the place of Vallabhbhai Patel and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

Verma’s idea behind the Arjak Sangh was to promote social unity of the SCs, STs and OBCs. Earlier, he was in the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), the chief opposition to the Congress. Led by Ram Manohar Lohia, SSP had become the symbol of anti-Congress-ism in the country. Lohia had coined the slogan “Sansopa ne baandhi gaanth, sou mein paavein picchde saat”. (Samyukta Socialist Party is adamant that the Backwards should get 60 out of 100). This slogan had paved the way for the OBCs’ association with the SSP. Verma also joined the SSP. As Verma was born in a village, he was conversant with the grim realities of rural India.

The socialists have been saying that a socialist cannot be a casteist person and vice versa. Recalling an incident from his political life in his book Kranti: Kyon Aur Kaise, Verma writes, “Mangal Dev Visharad had served as Minister for Public Works in Uttar Pradesh. During meals with his Bhumihar and other upper-caste colleagues at a village in his home district Azamgarh, he was made to sit at a distance and, for want for ‘pattals’ [plates made of leaves], served rice, dal and vegetables in a single ‘handiya’ [a clay pot with its neck broken to convert it into a plate of sorts] and water in an earthen lamp used in Diwali. What must have been going through the mind of this respected and scholarly Mangal Dev when he was subjected to this kind of humiliation and contempt? Can a Brahmin, howsoever poor he might be, ever imagine going through such an experience? Bhumihars may clean the utensils in which cows are fed, knowing very well that cows eat faeces; they have no problem washing the pots in which their pet dogs eat milk and roti. But they could not serve meals to Mangal Dev in metal utensils. Where else can one find such hatred, such contempt except in Brahmanism based on the idea of rebirth? When this is the treatment meted out to an ‘antyaj’ minister, the fate of crores of ordinary ‘antyaj’ Shudras and ‘mlecchas’ can only be imagined. Mangal Dev Visharad could not tolerate this humiliation and refused to eat. But only a handful of people can show such courage.”

Verma was a protagonist of total revolution. There was no middle course for him. He believed that a real and complete revolution would result in perfect equality in all the four facets of life – social, political, economic and cultural. Revolution is a much-abused word and few understand its real meaning. Some think that revolution is some kind of magic that will transform everything in a jiffy. On the contrary, revolution is just another name for consistent and continuous change. A re-rendition of the pre-ordained values of life in the interest of humanity is revolution. Though Verma was associated with Lohia’s SSP, he had ideological differences with him. Lohia was a Gandhian for whom Maryada Purushottam Ram and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi were idols. Ambedkar had said, “Uproot inequality and Brahmanism and dynamite the Vedas and the shastras.” No wonder Verma asked the workers of Arjak Sangh to celebrate the birth anniversary of Ambedkar as Chetna Diwas. He directed Arjak Sangh activists all over the country to burn the Manusmriti and the Ramayana from 14 April to 30 April 1978 to spread awareness among the indigenous inhabitants of India. The Arjak Sangh activists enthusiastically did that.

In 1967, Verma, an MLA, joined the coalition government led by Chaudhary Charan Singh as the finance minister. He presented a surplus budget and was the only finance minister of Uttar Pradesh to do so. During his tenure, he ensured the availability of literature on Ambedkar in all the government and non-governmental libraries of the state. Another government banned Ambedkar’s books Jatibhed Ka Ucched and Dharma Parivartan Karein and ordered seizure of the copies of the two books. Verma had a petition filed in the Allahabad High Court through Lalai Singh Yadav. The Allahabad High Court quashed the ban order. He filed a defamation case against the Uttar Pradesh Government and won damages.

Writing about the relationship between Lohia and Verma, well-known writer Mudrarakshas says, “When I met Verma ji at the bungalow of Dr Ram Manohar Lohia on Gurudwara Rakabganj Road, New Delhi, at around 1 pm, they were in the middle of a bitter argument on the Ramcharitmanas. Dr Lohia had a liking for the Ramcharitmanas and equally admired the Manusmriti.

Earlier, I had also confronted Dr Lohia over the Ramcharitmanas and Manusmriti. Lohia saw Hindutva from Gandhi’s perspective. He, of course, believed that many things in Hindu religion needed change and revision but he was not for the outright rejection of Hindutva. On the other hand, Ramswaroop Verma wanted freedom from Hindutva to initiate revolutionary and fundamental changes in Indian society. Dr Lohia did not agree with this approach. He had a big row with Lohia on this issue and that ultimately led to him parting ways with Lohia’s party.” Subsequent events proved how right Verma was. Later, Lohia developed close ties with the Janasangh. It is was his love for Hindutva that led Lohia to canvass for Janasangh chief Deendayal Upadhyay and that was why one of his close associates George Fernandes almost joined the BJP. Verma’s slogan was “Marengein, mar jayagein, Hindu nahi kahlayegein” (We will kill and we will die but we will not call ourselves Hindu). Dr Ram Manohar Lohia’s ideal was Gandhi and Gandhi’s ideal was Ram, who had taken birth for the protection of Brahmins and their religion. Gandhiji was a supporter of the Varna system, which was the factory of the caste system. Thus, it would be erroneous to describe Lohia as a socialist. The Ramcharitmanas described the backward castes as barbarians and base. But it was the ideal treatise for Lohia, who even used to hold Ramayana melas. Then, how could he be called a socialist? Lohia was not a socialist but a Brahmanvadi. On the other hand, Verma fought all his life for uprooting Brahmanism. Following in the footsteps of Buddha, Verma became his own lamp.

He bid goodbye to the SSP and joined hands with the well-wishers of Bahujans, such as Chaudhary Maharaj Singh Bharti, Babu Jagdev Prasad, Prof Jairam Prasad Singh, Laxman Chaudhary and Nandkishore Singh and, on 7 August 1972, laid the foundations of the Shoshit Samaj Dal. He gave the slogan:

Das ka shashan nabbe par, nahin chalega, nahin chalega,

Sau mein nabbe shoshit hain, nabbe bhaag hamara hai

[Ten cannot continue to rule over ninety. Ninety of hundred are exploited; we are the owners of 90 per cent (of resources)]

and

Shoshiton ka raj, shoshiton ke liye, Shoshiton ke dwara

(Rule of the exploited, for the exploited, by the exploited)

Ramswaroop Verma was firmly of the opinion that only social consciousness could bring about social change and social change had to precede political change; if, somehow, political change was brought about, it wouldn’t last long in the absence of social change. Verma was not interested in social reform; he was for social change. He used to say that if a piece of potassium cyanide was dropped into a can of milk and then drawn out, the milk would still be poison. He said that brahmanical values were not amenable to reform. Brahmanism couldn’t be reformed, it had to be banished.

Verma was first elected to the Uttar Pradesh Assembly from the Rampur constituency in Kanpur district in 1957 as an SSP candidate. He was re-elected in 1967, 1969, 1980, 1989 and 1991. In the assembly, the ruling classes were rendered speechless by his incisive, penetrating analysis and arguments. His supporters tore up the pages of the Ramayana in the assembly. They burnt the Ramayana and the Manusmriti in other venues. Verma tabled a Bill in the assembly that sought to put a stop to the grabbing of public land for building temples and mazars. The savarnas opposed the Bill. They said that such a move would fan communalism. Verma hit back. “Some people say that this will give an impetus to communalism. In Tamil Nadu, the government took over the control of 12,000 temples. There was no unrest there. The move did not whip up communal frenzy. Of course, if the Bill had said that the temples built on public land should be bulldozed, then there might have been unrest and violence. The Bill only says that the government would take over all places of worship, and the offerings made there would be government property. What is left from this amount after deducting expenses on priests and so on would be spent on projects sanctioned by the religion concerned. There is not a shred of communalism in this.”

While the Bahujans supported the Bill, the Brahmin MLAs were distraught. One of them, Ramautar Dixit, said, “We also don’t consider Ramayana a religious scripture. But burning it is not proper.” Responding to this line of argument, Verma said, “Dixit ji might not be considering Ramayana a religious scripture but when its copies were burnt in the assembly, it was said that it was a religious book. Gandhi ji had great reverence for this book. If the Ramayana is not a religious book, where is the need for this row?” Opposing the bill, another Brahmin MLA Brij Kishore Mishra said, “Whether this book is of ‘dharma’ or ‘karma’, you have no right to burn it.” Verma’s replied: “We burn our copies. We don’t burn your copies. As for the books, we have our own ideology and we have every right to put it before the people. You cannot stop us. The Ramayana was burnt in 1978 from 14 April to 30 April. It was done after distributing pamphlets that said that it was being done to raise consciousness. We burnt the Manusmriti, which is against the Constitution. We had burnt it and we will burn it again if such an opportunity arises. When Gandhiji had launched the non-cooperation movement, he had urged the people to burn foreign clothes. Now, clothes don’t hurt anyone. When we form our government, you will not speak in this language. Then, you will say the right things.”

Ramswaroop Verma never compromised on principles. He politics was based on principles. He passed away on 19 August 1988. He is not with us but his thoughts are very much alive.

Ramswaroop Verma (22 August 1923 – 19 August 1998) was born into a Kurmi peasant family of Gaurikaran village, Kanpur Dehat, in Uttar Pradesh. His father Vanshgopal and mother Sukhiya wanted that their son to acquire higher education. Verma was a brilliant student. He did his MA from Allahabad University and LLB from Agra University in an era when the institutions of higher learning were virtually out of bounds for the Shudras – though the British rulers were gradually easing restrictions on women and Shudras acquiring education. He studied Urdu, English, Hindi and Sanskrit. After completing his education, Verma had three options before him – joining the administrative service, practising law or serving the Bahujans of India through politics. Verma had cleared the written examination for recruitment to the IAS but even before appearing for the interview, he had decided on the course his life would take. He knew that he could lead a comfortable life by joining the IAS, but as a civil servant, it would not be possible for him to liberate the Bahujan community from its belief in fate, rebirth, superstitions, ritualism and miracles. On 1 June 1968, in Lucknow, he founded the Arjak Sangh for raising social awareness and consciousness. Ramswaroop Verma owed his political consciousness to a speech of Dr Ambedkar at the convention of the workers of Scheduled Castes Federation at Park Town Ground in Madras on 1944. Ambedkar had said, “Go and write on your walls that you want to be the governing community of the country so that you can remember it every time you walk past them. Another speech by Ambedkar at Begum Hazrat Mahal Park, Lucknow, on 25 April 1948, in which he said that the SCs, STs and OBCs would come on one platform; they would be able to take the place of Vallabhbhai Patel and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru.

Verma’s idea behind the Arjak Sangh was to promote social unity of the SCs, STs and OBCs. Earlier, he was in the Samyukta Socialist Party (SSP), the chief opposition to the Congress. Led by Ram Manohar Lohia, SSP had become the symbol of anti-Congress-ism in the country. Lohia had coined the slogan “Sansopa ne baandhi gaanth, sou mein paavein picchde saat”. (Samyukta Socialist Party is adamant that the Backwards should get 60 out of 100). This slogan had paved the way for the OBCs’ association with the SSP. Verma also joined the SSP. As Verma was born in a village, he was conversant with the grim realities of rural India.

The socialists have been saying that a socialist cannot be a casteist person and vice versa. Recalling an incident from his political life in his book Kranti: Kyon Aur Kaise, Verma writes, “Mangal Dev Visharad had served as Minister for Public Works in Uttar Pradesh. During meals with his Bhumihar and other upper-caste colleagues at a village in his home district Azamgarh, he was made to sit at a distance and, for want for ‘pattals’ [plates made of leaves], served rice, dal and vegetables in a single ‘handiya’ [a clay pot with its neck broken to convert it into a plate of sorts] and water in an earthen lamp used in Diwali. What must have been going through the mind of this respected and scholarly Mangal Dev when he was subjected to this kind of humiliation and contempt? Can a Brahmin, howsoever poor he might be, ever imagine going through such an experience? Bhumihars may clean the utensils in which cows are fed, knowing very well that cows eat faeces; they have no problem washing the pots in which their pet dogs eat milk and roti. But they could not serve meals to Mangal Dev in metal utensils. Where else can one find such hatred, such contempt except in Brahmanism based on the idea of rebirth? When this is the treatment meted out to an ‘antyaj’ minister, the fate of crores of ordinary ‘antyaj’ Shudras and ‘mlecchas’ can only be imagined. Mangal Dev Visharad could not tolerate this humiliation and refused to eat. But only a handful of people can show such courage.”

Verma was a protagonist of total revolution. There was no middle course for him. He believed that a real and complete revolution would result in perfect equality in all the four facets of life – social, political, economic and cultural. Revolution is a much-abused word and few understand its real meaning. Some think that revolution is some kind of magic that will transform everything in a jiffy. On the contrary, revolution is just another name for consistent and continuous change. A re-rendition of the pre-ordained values of life in the interest of humanity is revolution. Though Verma was associated with Lohia’s SSP, he had ideological differences with him. Lohia was a Gandhian for whom Maryada Purushottam Ram and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi were idols. Ambedkar had said, “Uproot inequality and Brahmanism and dynamite the Vedas and the shastras.” No wonder Verma asked the workers of Arjak Sangh to celebrate the birth anniversary of Ambedkar as Chetna Diwas. He directed Arjak Sangh activists all over the country to burn the Manusmriti and the Ramayana from 14 April to 30 April 1978 to spread awareness among the indigenous inhabitants of India. The Arjak Sangh activists enthusiastically did that.

In 1967, Verma, an MLA, joined the coalition government led by Chaudhary Charan Singh as the finance minister. He presented a surplus budget and was the only finance minister of Uttar Pradesh to do so. During his tenure, he ensured the availability of literature on Ambedkar in all the government and non-governmental libraries of the state. Another government banned Ambedkar’s books Jatibhed Ka Ucched and Dharma Parivartan Karein and ordered seizure of the copies of the two books. Verma had a petition filed in the Allahabad High Court through Lalai Singh Yadav. The Allahabad High Court quashed the ban order. He filed a defamation case against the Uttar Pradesh Government and won damages.

Writing about the relationship between Lohia and Verma, well-known writer Mudrarakshas says, “When I met Verma ji at the bungalow of Dr Ram Manohar Lohia on Gurudwara Rakabganj Road, New Delhi, at around 1 pm, they were in the middle of a bitter argument on the Ramcharitmanas. Dr Lohia had a liking for the Ramcharitmanas and equally admired the Manusmriti. Earlier, I had also confronted Dr Lohia over the Ramcharitmanas and Manusmriti. Lohia saw Hindutva from Gandhi’s perspective. He, of course, believed that many things in Hindu religion needed change and revision but he was not for the outright rejection of Hindutva. On the other hand, Ramswaroop Verma wanted freedom from Hindutva to initiate revolutionary and fundamental changes in Indian society. Dr Lohia did not agree with this approach. He had a big row with Lohia on this issue and that ultimately led to him parting ways with Lohia’s party.” Subsequent events proved how right Verma was. Later, Lohia developed close ties with the Janasangh. It is was his love for Hindutva that led Lohia to canvass for Janasangh chief Deendayal Upadhyay and that was why one of his close associates George Fernandes almost joined the BJP. Verma’s slogan was “Marengein, mar jayagein, Hindu nahi kahlayegein” (We will kill and we will die but we will not call ourselves Hindu). Dr Ram Manohar Lohia’s ideal was Gandhi and Gandhi’s ideal was Ram, who had taken birth for the protection of Brahmins and their religion. Gandhiji was a supporter of the Varna system, which was the factory of the caste system. Thus, it would be erroneous to describe Lohia as a socialist. The Ramcharitmanas described the backward castes as barbarians and base. But it was the ideal treatise for Lohia, who even used to hold Ramayana melas. Then, how could he be called a socialist? Lohia was not a socialist but a Brahmanvadi. On the other hand, Verma fought all his life for uprooting Brahmanism. Following in the footsteps of Buddha, Verma became his own lamp.

Ram Manohar Lohia

He bid goodbye to the SSP and joined hands with the well-wishers of Bahujans, such as Chaudhary Maharaj Singh Bharti, Babu Jagdev Prasad, Prof Jairam Prasad Singh, Laxman Chaudhary and Nandkishore Singh and, on 7 August 1972, laid the foundations of the Shoshit Samaj Dal. He gave the slogan:

Das ka shashan nabbe par, nahin chalega, nahin chalega,

Sau mein nabbe shoshit hain, nabbe bhaag hamara hai

[Ten cannot continue to rule over ninety. Ninety of hundred are exploited; we are the owners of 90 per cent (of resources)]

and

Shoshiton ka raj, shoshiton ke liye, Shoshiton ke dwara

(Rule of the exploited, for the exploited, by the exploited)

Ramswaroop Verma was firmly of the opinion that only social consciousness could bring about social change and social change had to precede political change; if, somehow, political change was brought about, it wouldn’t last long in the absence of social change. Verma was not interested in social reform; he was for social change. He used to say that if a piece of potassium cyanide was dropped into a can of milk and then drawn out, the milk would still be poison. He said that brahmanical values were not amenable to reform. Brahmanism couldn’t be reformed, it had to be banished.

Verma was first elected to the Uttar Pradesh Assembly from the Rampur constituency in Kanpur district in 1957 as an SSP candidate. He was re-elected in 1967, 1969, 1980, 1989 and 1991. In the assembly, the ruling classes were rendered speechless by his incisive, penetrating analysis and arguments. His supporters tore up the pages of the Ramayana in the assembly. They burnt the Ramayana and the Manusmriti in other venues. Verma tabled a Bill in the assembly that sought to put a stop to the grabbing of public land for building temples and mazars. The savarnas opposed the Bill. They said that such a move would fan communalism. Verma hit back. “Some people say that this will give an impetus to communalism. In Tamil Nadu, the government took over the control of 12,000 temples. There was no unrest there. The move did not whip up communal frenzy. Of course, if the Bill had said that the temples built on public land should be bulldozed, then there might have been unrest and violence. The Bill only says that the government would take over all places of worship, and the offerings made there would be government property. What is left from this amount after deducting expenses on priests and so on would be spent on projects sanctioned by the religion concerned. There is not a shred of communalism in this.”

While the Bahujans supported the Bill, the Brahmin MLAs were distraught. One of them, Ramautar Dixit, said, “We also don’t consider Ramayana a religious scripture. But burning it is not proper.” Responding to this line of argument, Verma said, “Dixit ji might not be considering Ramayana a religious scripture but when its copies were burnt in the assembly, it was said that it was a religious book. Gandhi ji had great reverence for this book. If the Ramayana is not a religious book, where is the need for this row?” Opposing the bill, another Brahmin MLA Brij Kishore Mishra said, “Whether this book is of ‘dharma’ or ‘karma’, you have no right to burn it.” Verma’s replied: “We burn our copies. We don’t burn your copies. As for the books, we have our own ideology and we have every right to put it before the people. You cannot stop us. The Ramayana was burnt in 1978 from 14 April to 30 April. It was done after distributing pamphlets that said that it was being done to raise consciousness. We burnt the Manusmriti, which is against the Constitution. We had burnt it and we will burn it again if such an opportunity arises. When Gandhiji had launched the non-cooperation movement, he had urged the people to burn foreign clothes. Now, clothes don’t hurt anyone. When we form our government, you will not speak in this language. Then, you will say the right things.”

Ramswaroop Verma never compromised on principles. He politics was based on principles. He passed away on 19 August 1988. He is not with us but his thoughts are very much alive.