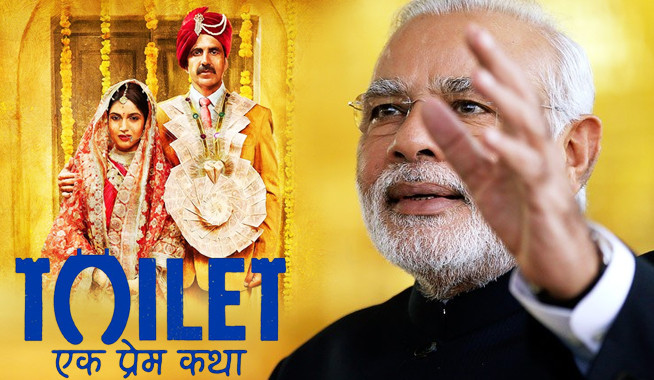

While most reviews and discussions of Akshay Kumar’s latest “movie with a message” Toilet: Ek Prem Katha have been debating whether the film gets lost in its propaganda or not, it is important to pause and reflect on the context and implications of this propaganda itself. The film is set in a small village in Uttar Pradesh, where superstitions abound. In a usual boy-meets-girl way, Keshav (Akshay Kumar) falls in love with Jaya (Bhumi Pednekar), a feisty well-educated young girl. They manage to get married, but the boy loses the girl because his house does not have a toilet – still the case in many villages across India. What follows is an unabashed movie-long advertisement for the Swachh Bharat Abhiyaan, covering multiple issues such as women’s empowerment and administrative corruption.

As far as prevention of diseases and the improvement of sanitation are concerned, open defecation is indeed a pressing issue in our country. But what the film-makers completely overlook is the peril of imposing an arbitrary deadline – Gandhi’s 150th anniversary – to make India ODF (Open Defecation-Free). In a country of billions, where the majority of the population still lives in rural and semi-urban spaces, how practical and beneficial is it to impose such a scheme? The Government of India under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyaan has issued instructions to households across the country to build toilets, defiance of which would require payment of huge fines. They will also be liable to other penalties like the revoking of ration cards. What Toilet does not tell you is that, for debt-ridden households across India, the Swachh Bharat Mission has become just another, and a crueler, means for exponentially increasing their debt, necessitating migratory labour – all for building a toilet in their homes.

Open defecation is a pressing concern not only for hygiene, but it is also about women’s safety, a fact rightly highlighted in the film through the character of Jaya. However, that these women are routinely shamed and harassed by the same administrators who are in charge of imposing the sanitation scheme, has not been exposed. For the implementation of the scheme, they have adopted means which are mostly coercive, and at times out-rightly illegal. Toilet is being numbered among films which deal with social issues, and yet, rather than depicting the ground realities of open defecation in the country, the film has papered over the problems of the very people whose cause it claims to uphold.

Divya Bharathi, the director of Kakkoos (Toilet), has said that she chose the cinematic medium to publicise the illegal employment of manual scavengers, and their horrifying fates because it has a wider reach and impact. Toilet being a mainstream film, with a star-studded cast, and well aware of its capacity to create an impact on the masses, chose to promote the state-sanctioned narrative of open defecation. By doing so, it further perpetuates an already skewed perspective on the Swachh Bharat Mission. This makes its status as a “social film” dubious.

The narrative resolution in the film is attained with the building of a toilet against all odds. But what happens once the film ends and the audience leaves? What happens to those people who have built these toilets with their blood money? Unwillingly saddled with a contraption which is alien to their lifestyle, will these toilets bring about an actual change in the sanitation practices of rural households? Will the rise in the number of toilets correspond to a rise in manual scavenging? What about the inhuman existence of these scavengers, whose state-sanctioned murders are rarely acknowledged? As opposed to the critically acclaimed Malayalam film Manhole, for a film apparently dealing with issues of sanitation, Toilet sadly fails to ask these uncomfortable yet necessary questions.

Also read:

By Dipannita Ghosh: #AintNoCinderella: Online Campaign Against Misogyny

Related articles:

Kakkoos – “This movie should evoke anger, not tears”

दलित छवियों से क्यों डरते हैं वे?

मैनुअल स्केवेंजिंग से हुई मौत – कहाँ है इंसाफ?