Akshay Kumar’s movie Toilet: Ek Prem Katha (A love story), releasing on August 11, 2017 tells the story of a young bride who walks out of her marriage when discovers that her in-law’s home does not have a toilet. The satire deals with open defecation and Kumar calls it his “contribution” to the Swachh Bharat Mission spearheaded by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The prime minister responded with words of appreciation for the film.

In the film, the young woman’s revolt leads to social change, but in real India, women do not appear to be a position to rebel–even if they are educated.

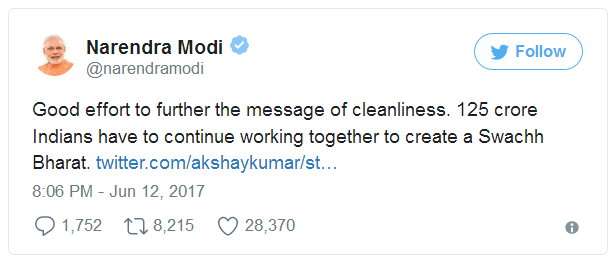

Women have limited decision-making powers in the construction of toilets in homes, according to a 2016 study conducted in Puri, a coastal Odisha district, by researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Women and girls are most vulnerable to problems associated with open defecation.

In 80% of households, decisions on the construction of sanitation facilities were made exclusively by men, the study found. In 11%, the decision was made by men in consultation with their wives, and in no more than 9% was the decision made by women.

These findings are relevant because only 37% of households in Puri district have improved sanitation, according to the National Family Health Survey 2015-16 (NFHS-4). However, this is higher than rural Odisha’s average of 23% and state average of 29.4% of households with toilets.

Improved sanitation facilities include the following: Flush to piped sewer system, flush to septic tank, flush to pit latrine, ventilated improved pit (VIP)/biogas latrine, pit latrine with slab, and twin pit/composting toilet, which is not shared with any other household.

The study sampled 475 households, of which 217 had no latrine, 211 had a functional one and 47 had one that didn’t work.

Only 42% of households in rural Odisha have individual household latrines (IHHL) under the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan (Clean India campaign), third lowest among states, according to government data.

Compared to households without latrines, households with functional latrines had more educated men and women, larger family sizes and higher incomes.

Households with latrines more often owned agricultural land (85%) and a tubewell (83%) and were less likely to be employed as share croppers or labourers, the study found.

‘Husband is the head of the family’: how social norms trump female literacy

Gender inequities within the family influenced decisions on sanitation too, interviews conducted during the study revealed. “After all, the husband is the head of the family, he is elder in age and in relationship and he will spend for the latrine, therefore, the decision making power lies with him,” said a 52-year-old woman.

Confined to the home and village, women also seemed to have little confidence in their decision-making skills, interviews showed. “We females don’t know anything. All things beyond my house boundaries are done by my husband, so they [husband and other males] can decide for the family’s welfare, not we,” said a 42-year old woman.

This is despite the fact that in rural Puri, 83% of women — and 92% of men – are literate, according to the NFHS-4 data. This is higher than the state average of 67.4% and 84.3% respectively.

A woman’s power to make decisions about marriage or visits to a healthcare centre are not necessarily strengthened by a high literacy rate or a better sex ratio at the state-level, IndiaSpend reported on February 13, 2017. This suggested the overpowering role of social norms that differ across India.

The IndiaSpend report, based on data from the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS) 2012, showed that almost 80% of Indian women said they had to seek a family member’s permission to visit a health centre. Of these women, 80% said they took permission from their husband, 79.89% from a senior male family member, and 79.94% from a senior female family member.

The IHDS survey in 2012 covered over 34,000 urban and rural women between the ages of 15 and 81, in 34 Indian states and union territories.“The bias against daughters can only end if women’s education is accompanied by social and economic empowerment,” concluded a study conducted over 30 years in Goa, Maharashtra, by Carol Vlassoff, a professor at the University of Ottawa, as IndiaSpend, reported in December 2016.

No jobs, limited bargaining power

Financial constraint was commonly cited as the reason for not building latrines or keeping them functional. The perception was that latrine installation is expensive, so men who controlled the household budget were not keen to build one. Those who had some money were reluctant to invest in latrines as they had other priorities.

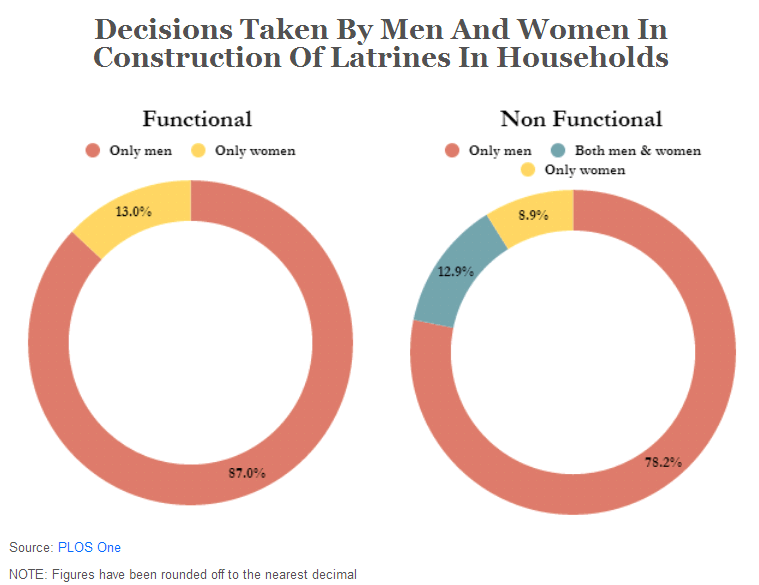

The study found that women see latrine construction as a “big decision” that men could take. Women relied on their husbands even for small purchases: “I alone cannot decide, we depend on them [husband] for every penny. Even for small things like purchasing bangles, saree for ourselves, we ask them for money.”

Even in other decisions involving money, women had limited bargaining power. For instance, in 91% households, only men took decisions on determining healthcare expenses for women. And 85% of women respondents were housewives, which probably limited their bargaining power. Puri district’s female work participation rate is 7.5%, third lowest among all districts in Odisha, according to the 2011 census.

NGOs focused on toilet building targets perpetuate gender inequality

The study found that even NGOs involved in latrine construction perpetrated these inequalities. They were given targets for latrine construction and field workers mostly approached men for faster permission to construct.

Women complained about this. “The NGO person looked for the males. They had meetings with them [husband and other males], and told us to dig a pit and keep it ready. One day, they came with a mason, and started constructing the latrine. He was the only mason to construct all the latrines in the village, so, due to his unavailability, he left the structure unfinished,” said a 65-year-old female respondent.