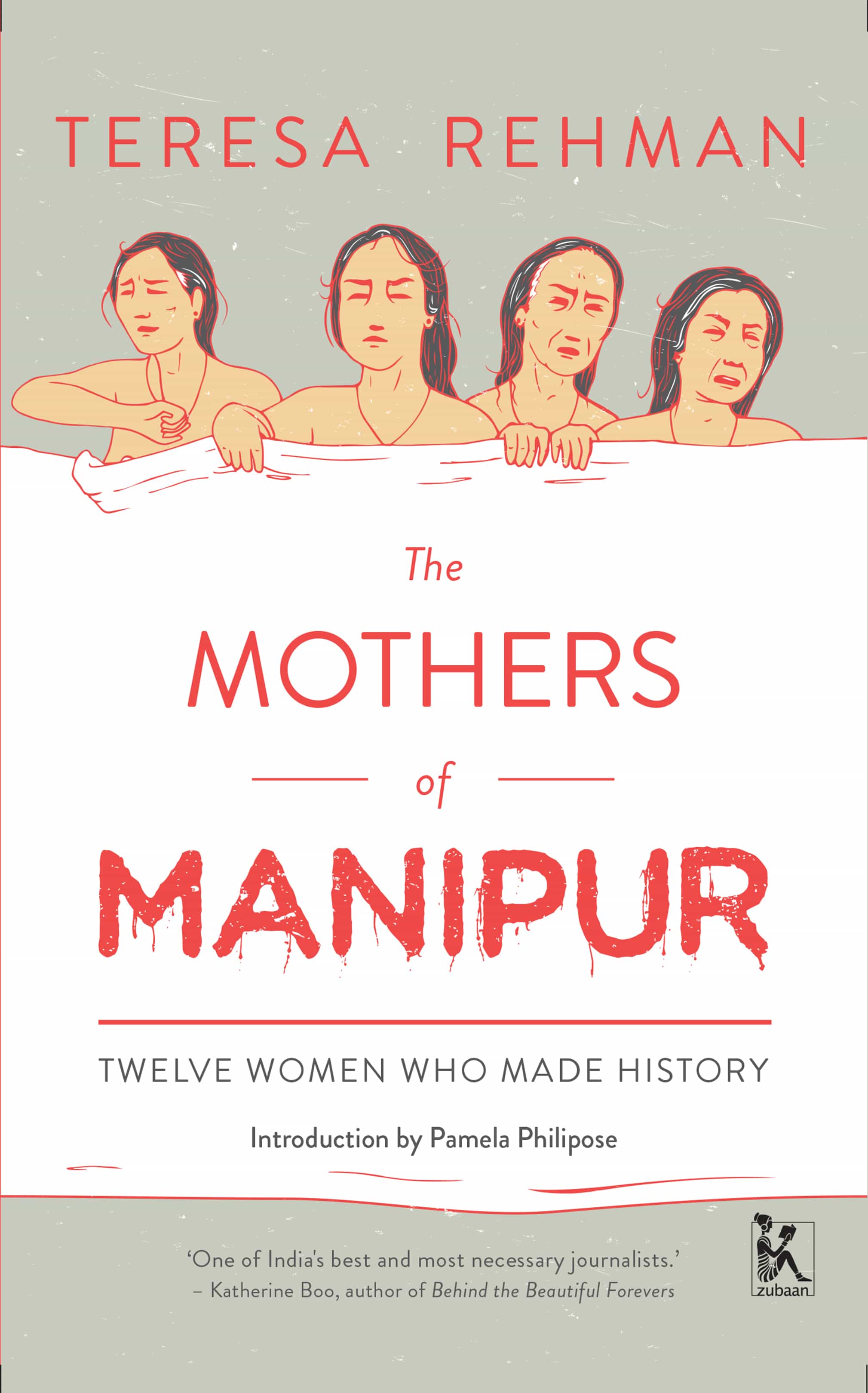

What was it about that protest which took place in 2004 that continues to resonate to this day, not just in the region where it played out but in the entire country and beyond? The images of Meira Paibis (women torch bearers of Manipur), some of them over 60 years of age, stripping outside the headquarters of the Assam Rifles at the Kangla Fort in Imphal, holds a significant place in the crowded annals of contemporary India… The trigger for the Meira Paibi action was the broken and abused body of Thangjam Manorama, with gunshot wounds on her genitals, caused by the Assam Rifles. Some of the women had visited the morgue and seen the body for themselves and, as they described its state to their sobbing colleagues, it compelled them to imagine a new language of resistance because the old ways of protest suddenly appeared shorn of meaning. It was as if their own, older bodies had to become that of Manorama’s and ‘off ered’ to her persecutors. Teresa Rehman, through her careful interviews with the ‘12 women who made history’ that are carried in these pages, provides us with telling snatches of that interior journey, even as the late summer heat merged with the simmering tension of the moment.

— From the Introduction by Pamela Philipose, Mothers of Manipur

Somewhere between the quiet pace of a small town and the noisy bustle of a metropolis is the city of Imphal. It is a pleasant enough urban space, although the sight of armed security personnel everywhere creates a deep sense of unease. The disquiet is obvious inside Ima Market too. Th e women who collect here to sell their wares are alive to the strife in the state, an unrest that has infiltrated into all of their lives, causing intense economic and social turmoil.

News spreads fast here and it is routine for Ima Ibemhal to listen to tales of torture, murder, killing, rape – these are part and parcel of life in Manipur. In the early 1980s, Ima could barely even remember the acronym AFSPA. Gradually, she learnt that it stands for the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, 1958 and grew wise to its many implications. Extended conversations with the other women in the market gave her insights into the problems that plague Manipur and also to the draconian Act. Her own life was touched by the violence when her older son, Tarun Singh, was abducted by the army and tortured so brutally that it left him with a permanent psychiatric problem, and her with a perennial scar in her life. In 1995, she was jailed for going on a hunger strike to protest the disappearance of a boy who had been picked up by the security forces.

In Ima Market, Ibemhal has earned a place of distinction. She is one of the mothers who participated in the iconic Kangla protest against the inhuman killing of Thangjam Manorama by security forces. ‘You cannot miss her shop and her smile. We are proud that she is one of us here,’ says Anima who owns a stall close to hers.

Besides being an active member of the Meira Paibi of her leikai, Ibemhal is also a social worker. She has been the President of the ‘All Manipur Tammi (valley)- Chingmi (hill) Apunba Lup’. There are several such groups who work and share ideas about how to work towards a peaceful co-existence between the people of the valley and those of the hills of Manipur. In July 2004, Manorama’s rape and killing shook her to the core and she went to the crucial 14 July meeting at Macha Leima. She was convinced that only an extraordinary protest would make the world sit up and take notice. She had felt impelled to reach out to billions of women around the world, make them realize what was happening in Manipur, how women were suff ering as soft targets. ‘It was acceptable even if I died while doing this; but I had to make people sit up and take notice of our plight. I was ready to die like a heroine – for a cause,’ she remembers.

And a heroine she truly was. For her, the day of protest was not an ordinary one: it was a day of communion with God.

She had come to the market and opened her shop as usual. No one at home had any clue about what she had in mind. A few of her close friends in Ima Market knew and tried to dissuade her. They also expressed misgivings about her ability to participate in something as unusual and out of the ordinary as a nude protest. But she gave them no heed – her mind was already made up.

Ima Ibemhal did not flinch for a second when the protest was staged. Her primary concern was the brutality with which Manorama had been raped and killed. ‘A message had to be delivered to the world. Manorama’s rape and killing was an assault on the dignity of women in Manipur and should never ever recur,’ she tells me.

On 15 July 2004, she had felt she was doing something propitious for her motherland. She had arrived at the Macha Leima office, taken off her gold earrings and bangles and after wrapping them in a piece of cloth, taken off her inner garments as well.

Many Imas had gone to the Kangla that day, but only 12 had stepped forward to disrobe. Ima Ibemhal remembers being totally engrossed in the protest and shouting ‘Indian Army Rape Us’ at the top of her voice. She also remembers having fainted because of the anxiety and stress and being taken to the J N Hospital.

Chitra Devi Chongtham, Ima Ibemhal’s youngest daughter who also owns a shop in Ima Market, comes to join in our conversation. She is followed by Ima’s second daughter, Thangjam Chaya, who also runs a shop in the marketplace. For both of them, memories flood in as they hear their mother speak about that ‘agonizing day’. Chitra becomes emotional, recalling how her brother had called her to inform them that their mother had been hospitalized: ‘Curfew had been declared and I could not go to the hospital. I felt helpless. But, I am proud that my mother could do something like this for the daughters of Manipur. I don’t think I would have had the nerve to do it.’

Chaya quips, ‘I was pained by the torment that caused my mother and the other Imas to even think about demonstrating in such an extraordinary way. The enaphi and the phanek are extremely signifi cant for Manipuri women and the enaphi, worn by married women, is very diffi cult to take off .’

After her release from hospital, Ima Ibemhal went back to a still and quiet home. Nobody asked her any questions, nor did she proffer any explanation. She laughs, ‘I did hear my sons telling their wives how embarrassing it was to go out of their homes, but they did not have the courage to say anything to me.’

Today, the people of the neighbourhood look up to Ima. She is everyone’s mother. Her family allows her to do whatever she wants. Even today, if there is a protest march and she is late, her children go and look for her in the hospital. They are filled with pride when their mother is featured in newspapers and in photo exhibitions. Her grandchildren jump up in delight when they see her in the media.

Only Ima knows how meaningless it all is. Nothing has happened even after poets have composed verses and journalists and writers have written paeans of praise on the Mothers’ Protest. Peace is fragile and she worries about the future of Manipur. She would never want her daughters to be compelled to stage a nude protest.

The irreverence of security forces, young men, born of mothers like her, angers her. ‘Without Imas they can’t exist,’ she says. She is proud of Kangla, which she feels identifies their culture. It hurts her that the tradition of our ancestors had been occupied by the army. In 2004, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh fulfilled the persistent demand of the people of Manipur and announced that the Kangla Fort, which was occupied by the Assam Rifles, would be evacuated. She feels that it’s a big achievement for them.

‘I wish they would develop some kind of respect for women and children. I hope that the decision-makers think about revoking the dreaded AFSPA,’ she says. She checks her mobile phone for any missed calls. Her eye wanders, her attention shift ing to another customer. As the Ima engages with the new buyer, I feel it’s time for me to leave. I smile at her and walk away.

Reproduced from Teresa Rehman’s Mothers of Manipur, Zubaan 2017, with permission from the publishers.