" The conclusion emanating from this state of affairs is simple and very disturbing: there is a radical dichotomy between the social organization of law as power and the organization of law as meaning. This dichotomy, manifest in folk and underground cultures in even the most authoritarian societies, is particularly open to view in a liberal society that disclaims control over narrative."

Robert Cover, "Nomos and Narrative", Harvard Law Review, 1983

Before I knew much else about where I had grown up, I knew it was “paradise on earth”. It hard to say exactly when notion took hold in the minds of people, though the exact words – firdous baroye zameen – are attributed to a Mughal king from the seventeenth century. That is how Kashmir has been broadcast in the imagination of both natives and Indians – as lush with bounties to be consumed from the cool of the mountain air, the green of the orchards, the water in its rivers to things like its famed shawls, saffron, apples and the like. But, each of these is not merely the thing itself for the act of consumption goes beyond the materiality of every consumable in the immediate sense.

Amongst the most iconic things Kashmir Ki, the papier-mâché box is one which embodies the contradictions of a place which is a disputed territory between India and Pakistan, the world's most heavily militarized zone and yet “paradise” at the same time. Part and parcel of a projection of Kashmir as a place where Indians should go to relax, get away from the summer heat and engage in the therapeutic purchase of beautiful things is the souvenir that will be placed at a place of pride in one's house or perhaps given to friends as token of a tour, a reminder of time spent on a shikara ride in the Dal Lake, riding horses in Gulmarg or Pahalgam. It is suggested that in “peacetime” Kashmir is as normal as any other place tourists may visit and if there is doubt that it is not, visitors should the construe of the presence of several hundred thousand army personnel as confirmation of having been secured.

Previously, I had spent hours perfecting miniature daffodils, tulips and begonias while learning craft of traditional drawing from a master-artisan but that a papier-mâché box could be a metaphor for matters legal came to me while I was working for the Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society [JKCCS], a civil liberties organization based in Srinagar. A case that I assisted in litigating and that received much media attention was that of the alleged sexual assault of a minor-girl in Handwara by a personnel of the Indian army on the 12th of April, 2016 following which four young-men and one woman were killed in army and police firing1. The case began when the girl's mother moved the High Court to file a Habeus Corpus petition on the 16th of April, 2016 on grounds that she did had not known of the whereabouts of her daughter and husband for four days after they were both taken into police detention. [Worryingly, in custody, the police had recorded a video of the minor girl, without her consent or presence of any family members, in which her identity was revealed, which was then circulated on social media.]

In response to the petition, the court chose to direct the police to file the grounds on which daughter and her father had been held when there exist numerous precedents in which constitutionally empowered courts in India, in response to Habeus Corpus petitions, have used their wide-ranging powers to direct the police to bring the person(s) under detention to the court within 24-48 hours. Again, despite being in police custody for a whole month, the court in its judgment, while directing the police to end its custody, ruled that there was “no question of illegal detention or confinement” of the daughter and her father, terming the custody as “protective” even if the family did not wish to see it so and had sought numerous times, from various state agencies, to be able to move about freely and without police surveillance. Further, the court made no mention of the deplorable video taken under custody or the fact that the daughter and her father had submitted that the police had forced them to sign applications requesting custody in the first place.

While the Indian intellectual elite insists that what is in fact structural violence needed to sustain military occupation, exemplified in cases including those of mass-rape and torture in Kunan-Poshpora, fake-encounter in Pathribal, massacre in Gaw-Kadal, Chittisingpora are aberrations, criminal acts most certainly, perhaps even exceptionally violent in many ways, but hardly symptomatic of the everyday condition of life in Kashmir for anyone may commit a criminal act on any day but this may be remedied though the legal process, which is available to everyone, everyday. Yet civil rights associations such as JKCCS, who have fought cases in the courts, say that there is not a single case in which personnel of the army have been prosecuted and punished in a court of law, despite decade long trials in some cases2. The lawyers who work here "fail" again and again, slowly exhausting every process via which "success" may be achieved. It is not just special laws such as the Armed Forces Special Powers Act [AFSPA] under which sanction must be granted by the Ministry for Home Affairs in New Delhi for any prosecution of army personnel in a court of law3 that are a factor – all judicial interpretation necessarily occurs within the limits of a normative framework at the level of ideas and is in return defined by such limits4.

In two years of my association with JKCCS, I have observed that when Kashmiris approach the court in such matters the presence of what can perhaps be described as judicial interpretation bounded by the realities of sustaining military occupation. This is taken to be an unspoken truth, a common sense matter-of-fact to be expected in a place like Kashmir. On the contrary, an expectation for judicial interpretation to make sense violations of civil and political liberties – such as in the case of alleged sexual assault I mentioned earlier – in a reasonable manner, not to speak of so called judicial activism, is thought of as based on an idealism that is far from reality. As aptly narrated to me by a survivor of mass-crime, when I asked him why he hadn't preserved a court judgment (I paraphrase), "We fight for the memory of our loved ones, but we know that the judgment is no taveez (amulet for protection) ".

As those who access spaces of the law in their professional practice or who approach the court here know, judicial interpretation is not an abstract process for it occurs within the realm of culture at large and material things in particular5 – myriad processes relating to the interactions with things paper are as integral to the legal process as any kind of strategy building. (The filing of affidavits, First Information Reports [FIR], status reports, writing of petitions, judgments, orders as well as processes such as indexing, stamping, photocopying and scanning simultaneously create a vast world of material culture within which the words of the law sit. Judicial paper for one is nearly impossible to obtain without a stamp from a notary. It is marked with the seals of the state and its agencies – an acknowledgement of the transformative power of violence vested in the law and used legitimately by the state6.

I understood the importance of such paper objects when I was researching five cases of mass-crime that our office had been litigating for a comprehensive report on militarization (presented before the United Nations Human Rights Council in September 2015). During fieldwork, I found instances in which the only material memory of a person killed or tortured in a case maybe the photocopy of an FIR in tatters, obtained by the family from the police after much hassle. The document lay in some corner of the house, forgotten in the everyday but remembered when asked for, as if recalled from a museum of lost time. In cases where the families decide to use the legal process their thumbprints, the turmeric stain from what they perhaps ate on the day of a hearing, the impressions of the drawer in which it sits, mark the paper.

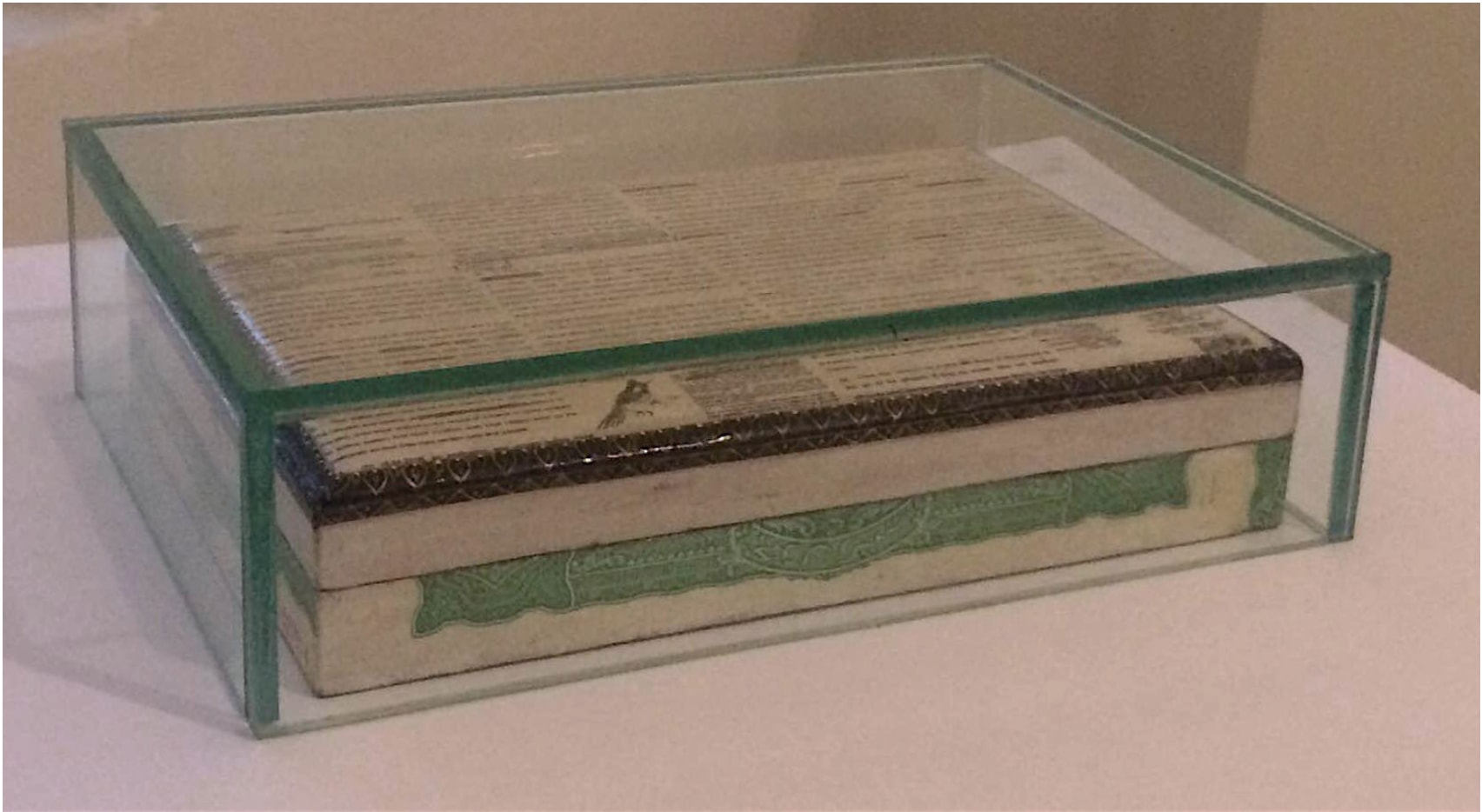

The world of paper is also that of 'chewed' paper–that of papier-mâché.

Papier-mâché boxes are of course bound spaces, opaque to what is inside them, accessible most easily on the surface-level. In papier-mâché, the box is created from newsprint, used books and copies; the outside of the box is hand-painted in highly stylized motifs, outlined in gold-leaf while the inside is most often simply painted black. The box is complete in itself, it is not intended as a keeper of something else. The gilded exterior is topped with layers of varnish until it acquires a mirror-like sheen of the kind where one sees one's face become part of a kingfisher-and- lotus-leaf design.

The occupation of Kashmir is not only about the much talked about “culture of impunity"7, the "inhuman"8 and "draconian"9 laws such the AFSPA, Public Safety Act [PSA], the scores of documented cases of disappearances, extra-judicial killings, torture and sexual violence but also about a certain set of ideas implemented through a socio- political process10 in which the trope of nationalism is tied to the consumption of things Kashmir Ki without seeking to be reflexive about the experiences of the people who produce such things or the role of such a consumption in providing a filter through which to tour a place with the proverbial rose-tinted glasses. It would seem that while the attribution of a context of beauty to things comes easy, for things do not speak, the same cannot be said of Kashmiris, whose chorus for Azadi reverberates in the streets every week.

What is apparent is that the Indian tourist is not distant from this scene, neither is she neutrally placed, in fact her assumptions and ideas form a part of the economy of which papier-mâché boxes are part11. Touring Kashmir is, in this context, a symbolic journey12 delineated by ideas of nationalism which when pursued by the millions can be thought of as an act of advancing, exploring possibilities for movement, for paradigms of nationalism in a certain landscape, possibilities that the next year can become precedent, in five a custom, in fifty… a map.

In the context of bound spaces, it is also relevant to ask, if judicial interpretations reflect only the norm, can we then take the law to be a voice of reason, of principle or morality? Are there parallels between ideas that encourage a fetish-like consumption of things Kashmir Ki and those that suggest a reasonable legal interpretation by is in fact possible in place of military occupation? What is it to engage with a legal system when one knows that the hope for reasonable remedy maybe an unreasonable hope?

Meanwhile, newer violations emerge everyday. In 2016, in the months-long curfew that followed the killing of rebel leader Burhan Wani, more than ninety protestors13 were killed and more than seventeen thousand injured14. Eight hundred have had their sight affected including a hundred who have been blinded completely15. Any sense of urgency in how the law may offer reparation for injury is rendered meaningless as the present is subsumed under the weight of the past, possibilities for the future are preempted, time is flattened and remedies perverted beyond recognition.

As the tourist season begins anew, visitors to Kashmir will continue to consume things Kashmir Ki and things legal will continue to consume Kashmiris themselves.

There is chewed paper, and then there are chewed people.

1. See reportage in the Indian Express titled "Handwara protests, Girl, father in custody, kin demand release", http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/handwara-killings-molested-minor- girl-in-j-k-police-custody- 2754220/.

2. Kazi, Seema, Between Democracy and Nation: Gender and Militarization in Kashmir, South End Press, 2011

.3. Kazi, Seema, "Law Governance and Gender in Indian Administered Kashmir," Working Paper Series, Centre for Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University, 2012.

4. Cover, Robert M., Violence and the Word, 95 Yale Law Journal 1601, 1986.

5. Derrida, Jacques, Paper Machine, Stanford University Press, 2005.

6. Derrida, Jacques, Acts of Religion, Psychology Press, 2002.

7. See report published by Allard K. Lowenstein International Human Rights Clinic at Yale Law School titled The Myth of Normalcy: Impunity and the Judiciary in Kashmir, 2009.

8. See Human Rights Watch, Everyone Lives in Fear: Patterns of Impunity in J&K. 2006, available at: http://www.hrw.org/en/node/11179/section/1.

9. Ibid.

10. Enloe, Cynthia, Understanding Militarism, Militarization and the Linkages with Globalization using a feminist curiosity, Women Peacemakers Program, 2014.

11. Copley, Stephen, "William Gilpin and the Black-lead Mine", The Politics of the Picturesque: Literature, Landscape and Aesthetics since 1770, Cambridge University Press, 1994.

12. Hunt, John Dixon, Verbal and Visual Meanings in Garden History: The Case of Rousham, Dumbarton Oaks Colloquia on the History of Landscape Architecture, 1992.

13. Waheed, Mirza in the Guardian, in a piece titled "India's crackdown in Kashmir: is this the world's first mass blinding?" See https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/08/india-crackdown-in-kashmir-is-this-worlds-first-mass-blinding.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.