Rarely do we see the optics of the periphery take over the centre or the mainstream. However, in the last two years, this is exactly what has been happening and it is mortifying. I am talking about the cases of lynching that are happening across the country on an everyday basis. What bothers me and at the same time makes me curious as a researcher, is the visuality of the violence. However, this visuality is not just limited to India, but has now become endemic across South Asia. This is not to say that lynching did not exist in South Asia earlier, it’s just the question of what has made lynching, and images of lynching, an everyday occurrence.

A disclaimer before I proceed further – I am in no way denying the instances of lynching that have happened prior to the cases I mention here. One is aware of instances of lynching that have happened in Delhi, Bangalore, Assam etc., over many pretexts. What this piece tries to argue is the ‘visuality’ of lynching.

Perhaps, one can trace the first public instance of lynching that became ‘viral’ on all our social media feeds to Bangladesh. In Feb 2015, Avijit Roy, the Bangladeshi atheist blogger was brutally hacked to death in Dhaka. His blood-soaked mutilated body lying limp on the pavement with his grievously injured wife, bleeding heavily, her arms outstretched asking for help, was circulated on every platform available. Barely a month later, our collective conscience was rattled by the lynching of a rape-accused in Dimapur, a town on the periphery of the nation-state’s popular imagination. What affected us about the lynching was the very act of lynching and the recording of that violence. The man, Syed Sharifuddin, was lynched not by some miscreants or extremists. He was, it seemed, lynched by a whole town and his dead, limp, brutalised and naked body was hung on the clock tower in the middle of the town. Photographs of this episode circulated widely, leaving most of us, gaping in horror. The former lynching was however, not done by a mob. It was the work of a few extremists.

Images from these incidents were perhaps the first that acquired viral status in recent times. And since then, such incidents and images have only multiplied. 2015 also witnessed the first instance of lynching over beef. Less than a year since the Dimapur incident, the politics of mob lynching, and visuality reached the northern parts of the country. Although the Dimapur incident was premised over a rape case, one cannot erase the fact that the accused was lynched so horrifically not because he was a Naga, but because he was an outsider, a Muslim. The hanging of the body in the town square was done precisely to make an example out of those ‘outsiders’ who dare to transgress their position in society. The next lynching came after six months and that was of Akhlaque in Dadri village in Uttar Pradesh. Images of his dead body did not become viral, but the images of the brutality did. Images of a blood splattered wall in his house, traces of blood on the floor, his blood-soaked clothes – they became viral in lieu of the absent body. This lynching over beef, was perhaps the first instance of mob killing over food habits. Many from the civil society were enraged.

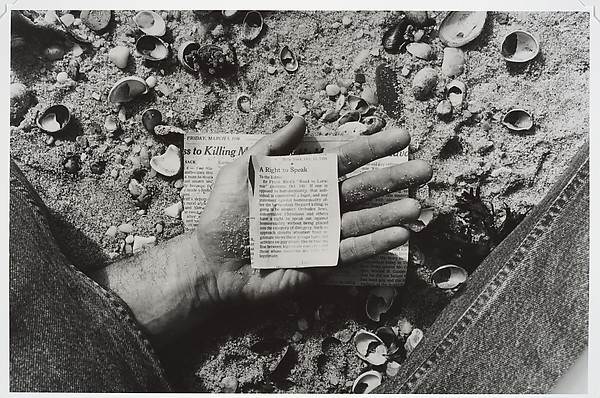

There was a lull in the killings post Dadri for a few months, soon to be followed by the killing of two cattle herders in Latehar, Jharkhand. The dead included a teenage boy. Their bodies were then hung from a tree with gamchas covering their faces. The starkness of the two bodies hanging without an audience somewhere in rural India was starkly different from the sheer mania of the crowd surrounding the lynched body in Dimapur. The Latehar image became iconic in its unintended reference to the lynching images of America from early 20th century, where Blacks were often lynched and their bodies hung from trees. Delirious crowds of white supremacists would surround these bodies in a carnivalesque atmosphere and take photos of them posing near the bodies as souvenirs. The image became the trophy of the act of killing the despicable and the aberrant other, who is not worthy enough to be a citizen of the nation-state. The Latehar image also refers to the images of the rebels killed by the British in Meerut during the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 .

By early 2016, the cartography of the violent, lynched body of the unworthy citizen, that aberrant citizen, became the contemporary post-human condition of Digital India. The premise, since October 2015, remained the same – killing in the name of cow, the ‘divine bovine mother’. The visuality now rendered itself beyond still images, it now consisted of videos too that were shared over WhatsApp in real time of the violence being perpetuated. This time the dirty, polluted body of the persecuted also included Dalits, the lowest among the castes in Hinduism, who are involved with skinning and disposal of dead bovine bodies. The high point against Dalit atrocities over the cow was reached in July 2016, when cattle skinners were brutally beaten in Una, in Gujarat. The video of this violence went viral and consolidated into a strategic and quite affective movement by Dalits against such brutality. But, even today, our outrage notwithstanding, lynching and killings in the name of cow continue unabated. One of the latest victim is the teenage Junaid, killed in train compartment near Delhi, a few days back. Here, the pretext of beef/cow was invoked to kill him, not because he was involved in any trade concerning cattle, but because he belonged to the dirty polluted community that consumes the cow.

What is interesting to trace is how the visuality of the violent and viral image has travelled to the rest of country. However, what one needs to keep in mind is that not all the cases have been committed by mobs, although the premise for the violence has remained the same. Many have been committed by members of self-motivated extremist cow protection groups. But what is noteworthy, is the lack of a bovine body or corpse, anywhere near where these cases of lynching. The few exceptions would be cattle traders ferrying the cattle on trucks or vans and being brutalised on the road with the vehicle in the background.

What I am trying to ferment as an argument, or even understand, is how and why did the visuality flow so fast from the periphery to the centre? Memory, as we know, is intertwined with the concept of the image. Images form part of the information network and landscape. So, when we are talking of the visuality of lynching, we must keep in mind that equally important are the text messages circulated on WhatsApp, along with these images, by both perpetrators and victims. The text messages exhort the ideal Indian citizen to do his duty by getting rid of the dirty polluted bovine consuming unworthy citizen from the holy land of the Ganga. It exhorts the reader to be the ‘nationalist citizen’ and do his duty for the nation state by erasing these unwanted elements. These are then followed by the act of violence, which often ‘leaks’ out in social media, following which mainstream media picks it up.

The trend, however, is that what was once an act unthinkable in the centre, has now become the new normalised for the centre. The act of lynching has become the new normal for our screens. India in 2017 resembles the US of the 1920s. Almost a century apart temporally, but spatially, we occupy the same space. The act of lynching in India, cannot even be called vigilante justice anymore. The media as the image and the apparatus, facilitates this ‘swarm’ of public. The swarm here is, to borrow Jussi Parrika’s argument, ‘…more than ideology at work. The swarm is not merely a quirky metaphor adopted from biological discourse… the swarm is an infrastructural constitution of relations of sensing, data processing and feedback structures and it increasingly constitutes what we as so-called humans are able to perceive’. And this perception is the perception of violence, to be able to read this violence as it really is mediated through the image and the apparatus. Welcome to the visuality of Lynchistan.