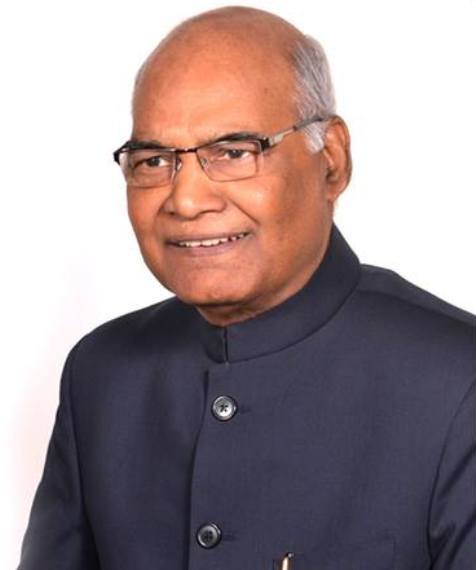

Both the government and the opposition have sounded the bugle for the president’s election by announcing Dalit candidates. On the one hand, the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) has fielded former Bihar governor Ram Nath Kovind, who hails from the Kori/Koli community. On the other hand, the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) has nominated former Lok Sabha speaker Meira Kumar, the daughter of former deputy prime minister Jagjivan Ram; she comes from the largest and most influential Dalit caste – in terms of numbers and participation in governance. In other words, this has become a Dalit-versus-Dalit contest. The two dominant political alliances, who represent today’s political rivalry, did not suddenly find themselves at this Dalit chessboard. There was the institutional murder of Rohith Vemula, atrocities of Una and Saharanpur, Dalit resistance, the skullduggery of those in power, and now there is this election for the president being fought on the Dalit chessboard.

The history of appeasement

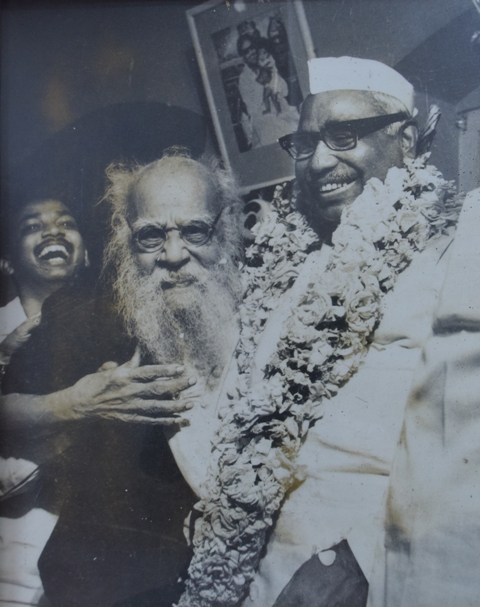

A symbolic Dalit representation points to a Dalit vote-bank, and Dalits as an influential force in politics that those in power are trying to please. But it also points to a need for Dalit politics to remain cautious and alert. Try and recall the moment when Dalit issues started figuring in the Indian National Congress’ agenda. That was when Babasaheb Ambedkar’s presence began to be felt in Indian politics. It was after Ambedkar burnt the Manusmriti, and fought for and demanded a separate Dalit electorate that Mahatma Gandhi incorporated Dalit issues into his movement for social reforms. He named the magazine he edited ‘Harijan’. On the one hand, Ambedkar’s was a politics that revolved around the abolition of Varnashram and caste, while on the other hand, Mahatma Gandhi’s was a social movement that supported the Varnashram, yet declared itself anti-caste. This was the first instance of a politics of appeasement and it was a response to Ambedkar’s politics. Whose interests the two leaders had in mind was revealed when Gandhi stubbornly sat on a fast and the Poona Pact was signed in 1932. Ambedkar had to give up his demand for a separate electorate before the two leaders reached an agreement on reservations. The politics of appeasement picked up. Jagjivan Ram became the first weapon of Congress’ policy of appeasement against this backdrop of Ambedkar’s politics. He went on to play a long innings in Indian politics.

The Sewagram Ashram in Maharashtra, which Mahatma Gandhi set up in 1936 next to a Dalit-majority district, became the centre of ‘Harijanodhar’ (Harijans’ deliverance) experiments. Dr Ambedkar was in favour of a clear, interventionist participation in the State and society and not just symbolism. Gradually, Ambedkar chose a path clearly distinct from the others, resulting in his conversion to Buddhism. Dalits began feeling unattached in terms of religion and culture and indebted to none. Kanshi Ram gave Ambedkar’s path a political form when he made Dalit politics stand on its own feet in Uttar Pradesh, the state that is India’s largest and politically very important. The state went to have Dalits in power in the true sense of the word. Consequently, the policy of appeasement underwent a change.

Are we back in the age of appeasement?

In Uttar Pradesh, the ‘daughter of Dalits’, occupying the most powerful post, began trying to appease Brahmins using symbolism, ostensibly to bring about social equality. The search for Brahmin faces began. Ramdas Athawale, a strong Dalit leader from Maharashtra who is now a state minister at the Ministry of Social Justice, recommends 3 per cent reservation for Brahmins because all he has is self-confidence as a politician. Appeasement is aimed at people like him whose votes are important but who don’t or no longer have decisive roles in power. So, then, has another round of Dalit appeasement begun? Are Dalits being turned into a Dalit vote bank again? Has the state fallen into the clutches of the forces that believe in Chaturvarna and Varnashram? The answer is yes. Hence, the dominant communities are bringing forward their handpicked faces to stand in the way of a total societal transformation. If Dalits are being oppressed, if they are being asked to leave socio-cultural institutions where they have been agents of change, then those brought to the forefront to defend the State may have a Dalit identity but they will be those who stand with the State. Even the Congress candidate who defeated Babasaheb Ambedkar was a Dalit and Dalits were leading those who pelted stones at him in Bihar. Today, when attacks on minorities have increased, the state has found members of the minority communities – like Shahnawaz Hussain and Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi – to speak up for it.

BJP has resorted to extremely regressive appeasement

Historically, appeasement can be traced to the Congress and Mahatma Gandhi but today the BJP is doing a politics of Dalit appeasement that will be more dangerous in the long run. The BJP is not only the political representative of caste-patronizing Hindutva in principle, but it is the political heir of those people who had opposed Ambedkar’s political goals. They were the ones who were lobbying for Manusmriti as India’s Constitution. They are the same people who are actively working towards social harmony instead of social equality. In other words, they want Dalits to be satisfied with the permanence of their plight and status, and commit themselves to fate, god and those in power. This is the truth about the BJP, which is the political representative of those who lobby for the continuation of their present comforts. This is the reason the BJP is discouraging the political, intellectual and academic leadership of those castes among Dalits capable of bringing about social, economic and cultural change and is creating the false impression that it is providing opportunities to the less influential castes. It is not just among Dalits that the BJP and the RSS have employed this form of deception. They have from to time raised up OBC leaders to represent Hindutva and to oppose Mandal and reservations. This politics can be described as ‘all-encompassing’ instead of ‘all-inclusive’. We have this symbolic Dalit representation today but it should make us more alert, less celebratory. For the opposition to Dalit politics today is more complex than ever before.