The phenomenally versatile Dilip Chitre wrote in one of his well-known poems:

The Czar Peter opened up a window on Europe

From where the bankrupt poets of the future saw

A mysterious navy well-armed with battle-ready poetics

Advancing on Russia.

I, a Marathi poet, walk on Nevsky Prospekt

Looking at the grand buildings on either side,

Realising that these monuments had no poet in mind.

The gaze that spanned the civilisations that he witnessed in the empires home and abroad longed for a space for poets. A Marathi poet, and translated to wide popularity, Chitre’s work was especially honoured by Abhidha, a literary magazine brought out in 1992 by poet and editor Hemant Divate. It started by giving a platform to new poets and critics in Marathi for seven years before metamorphosing into Abhidhanantar which enriched the Marathi literary scene in the post-nineties, providing a solid platform to poets irrespective of their different social, cultural backgrounds and geographical locations.

Poet and critic Sachin Ketkar, in a speech at the recent Mumbai Poetry Festival, outlined the rise of Marathi poetry, traced the origin of Abhidha from a small town of Shahpur, a Taluka place in Thane District, one year after the economic reforms initiated by the then Prime Minister PV Narsimharao and the finance minister Dr. Manmohan Singh, and two years after the implementation of the Mandal Commission Report by the VP Singh government and three years after the fall of the Berlin wall which put an end to the Cold War.

“The same year saw the demolition of the Babri Masjid, and three years later, the Internet would be made publicly available in India. Under the policies of liberalization and privatization, television saw an explosive growth by 1995. Needless to say even today, the global neo-liberal logic behind economic reforms, the politics of Mandal, Kamandal and Media, informational technology revolution and the global demise of left-liberalism and multiculturalism plays a significant role in our lives. What is understood as ‘contemporary’ in 2017 has largely been shaped by the processes that gained momentum in the post-nineteen nineties period,” Ketkar said.

In the second innings, ‘Abhida’ was reborn as ‘Abhidhanantar’.

Ketkar mentioned that in the first issue of Abhidhanantar in 1999, the editor wrote: “Abhidhanantar that started out as movement of poetry, of poets and for poetry has assumed now the form of an expansive forum. It is going to deliberate upon the place of Marathi language after globalization, the place of Marathi in the wider context of world literatures, and linguistic, literary and cultural changes that have happened after globalization. In short it is going to be a cultural and literary ‘vyas peeth- (forum). It is also going to hunt for new talents by organizing poetry competitions, workshops, translation workshops and so on.”

“The movement has largely remained faithful to this vision,” he said.

“Abhidhanantar consistently gave the Marathi language a new direction in literature, presenting new, different and contemporary poetry and literature for more than seventeen years,” said Smruti Divate, founder and director, Poetrywala, an imprint of Paperwall media.

Little surprise that Abhidhanantar has had several important special issues dedicated to literary stalwarts like Dilip Chitre and Arun Kolatkar. What was of most importance is that it focused on the effects of globalisation on Marathi poetry, a trend which was immensely impactful and relevant but surprisingly not acknowledged by other poets, according to Divate.

Author and activist Salil Tripathi stirred the audience’s imagination in his keynote address titled “Where the mind is without fear”. He first evoked Mangalesh Padgaonkar in a Marathi poem where the poet caustically says “salaam” to all forces of fear and cowardice to highlight the lacuna in collective action:

Salil Tripathi delivers his keynote speech at the Mumbai Poetry Festival. 27 April, 2017. Photo by Mustansir Dalvi.

Tripathi inevitably evoked Tagore next posing the question if we really live in a country where the mind is without fear and the head is held high:

The participating poets and the audience were left with the stark truth that “We live in a time where the liberal imagination is under threat”, as put forth by Tripathi.

Perhaps what he offered by turning Tagore’s invocation into a plea clothed by sarcasm

“ Into that hell of serfdom, my country lies: we hold the wake.”

is the wake-up call of our times.

And on this note, Tripathi mentioned writers Keki Daruwala, Mangalesh Dabral, Jayanta Mahapatra, Ashok Vajpeyi, Nayantara Sahgal, Krishna Sobti, Rahman Abbas, Sangamesh, and “dozens of others who returned their awards to the State, protesting its silence over the murders of Malleshappa Madivalappa Kalburgi, Narendra Dabholkar, and Gobind Pansare.”

The Mumbai Poetry Festival, April 22-23, celebrating 25 years of Abhidha’s journey, saw a huge swathe of poets from India and abroad regaling Mumbaikars and other outstation visitors with poetry and discussion ranging from aesthetic, politics, protest and love. Marathi, Gujarati, Arabic, Bangla, English, Urdu, and Hindi poetry from new and veteran poets formed a cornucopia of sounds and rhythm over these two days.

Ketkar’s delineation of Abhidhanantar’s evolution was pithy.

“Abhidhanantar is a unique phenomenon, to an extent that I haven’t heard of any parallel movements in literatures I am familiar with, that is, Gujarati, Hindi or Indian poetry in English. “

He offered a critique in the process.

“The last movement I have heard of in Gujarati is ‘Parishkruti’-Gadyaparva (now Sahcharya) movement in the nineties whose ideological thrust is similar to the nativism and identitarian cultural politics (like Dalit, workers, feminist, grameen, Muslim Marathi and so on) that pervades the post nineteen sixties Marathi literature and literatures in other Indian languages. Such movements are marked by their remarkable absence in Indian poetry in English. Indian Poetry in English was insulated from these social and cultural movements largely due to upper-caste, urban and elitist location of English language itself in India that was challenged in other Indian languages after the sixties.”

Divate’s Poetrywala is an imprint dedicated solely to poetry. Launched in 2003, it makes it possible for poets writing in various Indian languages besides English to get published. In the last 14 years, Poetrywala has published some significant books of poetry in English and Marathi, as well as English translations of various Indian languages and foreign languages.

The strong and sustained publication of Abhidha and Abhidhanantar for 18 years indeed seems to have augured good times for Indian poetry. Abhidhanantar has been credited for providing a solid platform to new poets and for enriching the post-nineties Marathi literary scene.

Divate informed that the Abhidhanantar Award constituted only once comprising of a cash prize of Rs. 25,000 and 11 consolation prizes of Rs.1,000 each have brought some amazing new talent in Marathi poetry to the forefront.

The activities of the journal have encompassed several other areas related to the growth of poetry. A daylong seminar to discuss the impact of globalisation on life and poetry titled ‘Nave Jagne, Navi Kavita’ has been held at various locations in Maharashtra. A daylong seminar on the works of Chitre in 1996 was a major highlight where Marathi literary stalwarts such as R G Jadhav, Purushottam Patil, Vasant Abaji Dahake, Prabhakar Bagle, Pradeep Karnik, Shridhar Tilwe and others presented their papers/views on Dilip Chitre’s work, which were later published in the Dilip Chitre special issue of Abhidha.

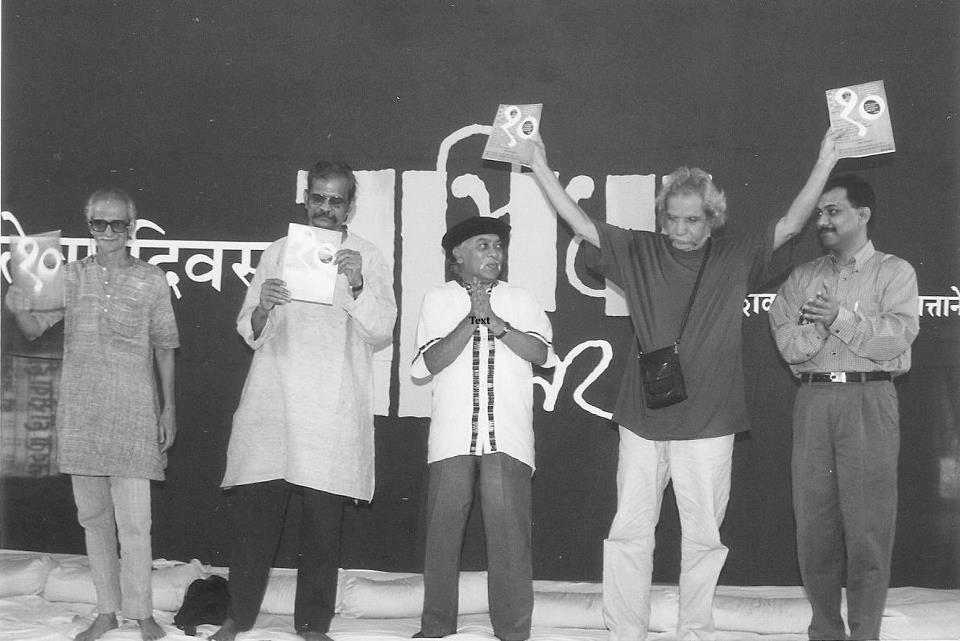

Launch of the 10th anniversary issue of Abhidhanantar in Mumbai on 6th October, 2002, attended by the stalwarts of Marathi literature.From L-R are Ashok Shahane, Publisher-Pras Prakashan, Vasant Abaji Dahake, Dilip Chitre, Arun Kolatkar releasing the issue in his style and Editor-Publisher of Abhidha and Abhidhanantar Hemant Divate.

Launch of the 10th anniversary issue of Abhidhanantar in Mumbai on 6th October, 2002, attended by the stalwarts of Marathi literature.From L-R are Ashok Shahane, Publisher-Pras Prakashan, Vasant Abaji Dahake, Dilip Chitre, Arun Kolatkar releasing the issue in his style and Editor-Publisher of Abhidha and Abhidhanantar Hemant Divate.

On the tenth anniversary festival of Abhidha, a day-long festival called ‘Kavitecha Divas’ was celebrated. For the first time, Arun Kolatkar, Dilip Chitre, Vasant Gurjar, Ashok Shahane, Gurunath Samant and Satish Kalsekar came together on the same platform and read their poetry.

Kolatkar, regarded as the genius of modern Indian poetry in English, had written:

I have a pen in my possession

which writes in 2 languages

and draws in one

__

My pencil is sharpened at both ends

I use one end to write in Marathi

the other in English

__

what I write with one end

comes out as English

what I write with the other

comes out as Marathi

No other verse perhaps captures better the relevance of bilingual literature in India than the above. What Kolatkar, with his uncanny sense of the future, had already realised then is what Abhidha and AbhidhNantar picked up from. Translation and English writing, both were the pen that was to be held aloft by writers and critics very soon with encouragement from Divate’s magazines.

At the Mumbai gathering, poet K Satchidanandan brought a much nuanced finale themed “A prayer for peace” to the gathering in which he summing up the state of poetry in our modern times.

“Brecht was right when he asked, “Will there be poetry in dark times?”, and answered, “Yes, poetry about dark times”. Remember, in his poem ‘To the Posterity’ he had bemoaned the cruel times when a talk about trees could be a crime since it also carried a silence about so many crimes,” Satchidanandan said in his valedictory address. “We too are passing through a bleak time when all optimism looks facile and the only honest poetry seems to be of despair and sarcasm.”

Before he read out his well known poem “Gandhi and Poetry”, he solemnly pointed out that “it is impossible for the genuine writer today to ignore the violence that threatens” us today. “Blood floods our bedrooms and our drawing rooms are strewn with corpses and that is often the blood and corpses of those who have neither drawing rooms nor bedrooms. Even the ivory towers of pure aesthetes are being swept by the winds of violence and change. Poets can no more be comfortable with ahistoricity, even if they transmute it, as Paz says, into apocalyptic visions.”

If one considers how then ahistoricity was brought into question, the Mumbai Poetry Festival saw in attendance the 88-year-old doyen Jayanta Mahapatra along with names such as Keki Daruwala, Vasant Abaji Dahake, Mangalesh Dabral, Priya Sarukkkai Chabria, Rati Saxena, HS Shivaprakash, Ranjit Hoskote. The sheer range of ideas had the festival goers in a tizzy.

A film screening by Prabodh Parikh on the Gujarati poet and writer Labhshankar Thaker (On Being Human) elicited exciting responses. The biopic raised questions of the art of poetics and its inward performance to relate to societal issues. Another stirring performance was from Parnab Bhattacharya who presented poems of Mahashweta Devi and Nabarun Bhattacharya in his inimitable style.

“Poetry is gathering momentum and that’s a wonderful sign indicating that there is still hope for humanity,” Divate summed up.

The spirit of Abhidha and Abhidhanantar continues in the joint vision of Chitre and Kolatkar. The monuments where poets would dwell and a pen that only a forked tongue will wield are the metaphors that sustain the journey undertaken by these journals. Hope remains that this 25-year celebration will address our collective poetic template to make more poetry in Indian languages, including English, accessible to readers at home and abroad.

More on poetry in the Indian Cultural Forum:

Watch an interview with Vivek Narayanan here:

Read poems from several languages and their English translations from the Guftugu archives.

Listen to Gauhar Raza recite his poems here.