Given the prominence gained by Dalit literature over the past two decades, I was under the impression a sizeable number of Dalit litterateurs must have been honoured by different literary organizations. However, when I analyzed the list of awardees of the Sahitya Akademi, I was in for a surprise. I discovered that not a single Dalit had won the Sahitya Akademi and Jnanpith award from 1955 to date. Only two women figure among the recipients of the awards. When I delved into the history of Sahitya Akademi and the Bharatiya Jnanpith – the organizations that have instituted these awards – to investigate the reasons behind the lack of social and gender diversity among the awardees, I was shocked.

In 1944, long before Sahitya Akademi, India’s most prestigious literary institution, came into existence, the British government had approved, in principle, the proposal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal that a “National Cultural Trust should be constituted to promote cultural activities in all regions of the country”. The proposal was to establish national academies of literature, visual arts, music, and dance and theatre. The government of independent India implemented this proposal. It passed the resolution No F-6-4/51G2(A) dated December 1952 to establish a national academy of letters called Sahitya Akademi and then followed up with the inauguration of the academy on 12 March 1954. The resolution described it “as a national organization to work actively for the development of Indian letters and to set high literary standards, to foster and co-ordinate literary activities in all the Indian languages and to promote through them all the cultural unity of the country”.

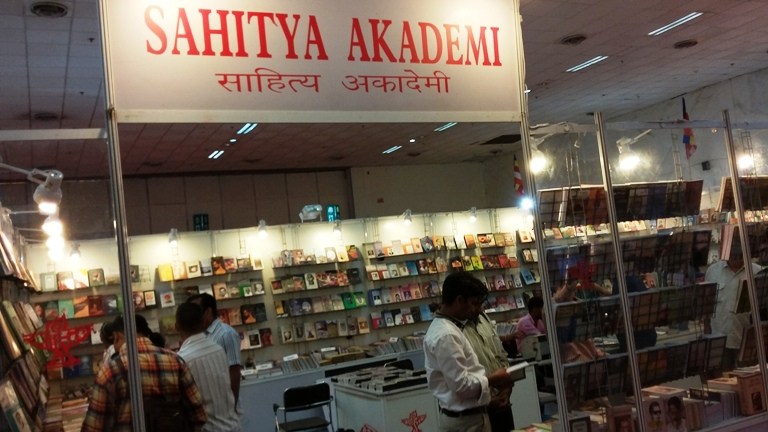

Though set up by the Government of India, the academy functions as an autonomous organization. It was registered as a society on 7 January 1956, under the Societies Registration Act, 1860. Sahitya Akademi is the central institution for literary dialogue, publication and promotion in the country and the only institution that undertakes literary activities in 24 Indian languages, including English. It has so far published more than 4200 books, the present pace of publication being one book every 30 hours. Every year, the Akademi holds at least 30 seminars at the regional, national and international levels, along with the workshops and literary gatherings – about 200 every year – under various heads like Meet the Author, Samvad, Kavisandhi, Kathasandhi, Loka: The Many Voices, People and Books, Through My Window, Mulakat, Asmita, Antaral, Avishkar, Nari Chetna, Yuva Sahiti, Bal Sahiti, Purvottari and Literary Forum. It has also system of electing eminent writers as Fellows and Honorary Fellows.

The taxpayer funds this organization. It is run not by thugs and mafias that have come to dominate politics but by well-known people whom we consider top intellectuals. It is natural for us to expect high standards from them – that they will leave no stone unturned in democratizing the institution. But the Sahitya Akademi, which has been managed by 250-odd authors in 24 languages over the past seven decades of its existence, is far from being democratic. Had it been democratic, of the 4200 books published by it, at least 900 would have been based on Tribals and Dalits and of the 30 big seminars organized by it every year, at least 15, if not 25, would have been centred on Tribals, Dalits, OBCs and minorities. Similarly, at least 100 of the 200 programmes organized by the academy like the Meet the Author, Samvad, etc would have been about authors from these communities and a sizeable number of its Fellows and Honorary Fellows would have been from these sections. But that is not so. Instead, the Sahitya Akademi seems to have been reduced to “a national organization working actively for the development of savarna letters” and its undemocratic working is promoting cultural bitterness instead of cultural unity. A visit to the website of the Akademi reveals why this institution, which is chock-a-block with top litterateurs, is so singularly devoid of democracy. The surnames of the members of the administrative, publications and awards selection committees are an eye-opener.

Savarna males form 80-85 per cent of the members of the Executive Board and the Advisory Board of the Akademi. Of them, more than 60 per cent are Brahmins. SC, ST, women and minorities together do not make up even 15 per cent of the members. It is these 80-85 per cent members who play the decisive role in selecting the recipients of the awards, books to be published and Fellows and Honorary Fellows. Why has the Akademi been turned into an institution for fostering the literature of a minority section of the Hindus, which was already developed in the Vedic era? The sociological reason for this is that in India, a person cannot think beyond the interests of his caste or varna. No one – from the greatest of the kings to biggest of the politicians to saints, to writers, to artistes – has been able to rise above the narrow considerations of caste and creed. If the Sahitya Akademi is to be transformed into an institution working for the development of Indian – not savarna – literature, a powerful campaign should be launched to introduce gender and social diversity in its Executive Board and Advisory Board. There is no other option.

Sahitya Akademi is not the only awards body carrying this affliction. From Bharat Ratna to Yash Bharati – savarnas are dominant in the juries of almost all the awards. Till adequate representation of all social groups is ensured in these bodies, the awards will continue to be the monopoly of the savarnas – who will continue to use the awards to become rich and famous.