I have peeled away the skin of my life and served it up to you. Some may say this fruit is inedible but that doesn’t matter.

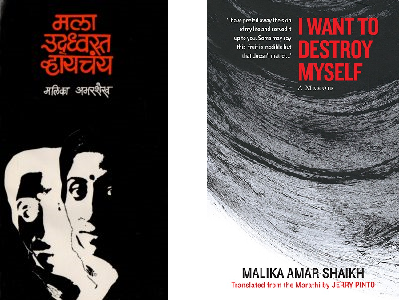

These words appear in the opening of Malika Amar Shaikh’s brutal 1984 Marathi memoir, Mala Uddhvasta Vhaychay, and they stick with you long after you’ve turned the page. I say brutal because this is not a book you can move on from.

Shaikh is a poet, writer and theatre person, daughter of the Marathi shahir Amar Shaikh, a trade union leader and legendary folk singer and a Marathi Hindu mother who was a fellow Communist party worker. Her memoir, now available in a new English translation by Jerry Pinto (published by Speaking Tiger), titled I Want to Destroy Myself, is a chronicle of a promising young life as well as a destructive marriage (to the co-founder of the Dalit Panthers, Namdeo Dhasal, no less).

And it leaves out nothing: you see Shaikh hit puberty; have sex for the first time; have an episiotomy in a filthy hospital during the nightmare of delivering her child; you see her fall down in a faint from the pus-filled boils on her groin from venereal disease — a gift from Dhasal, who would visit sex workers and continue to have affairs through their marriage. You see the emotional battles between her and Dhasal, her own bad behaviour as well as his, the freezing of their marriage when you realise, along with Shaikh, that she isn’t seen as an equal, and the blows, the fights, the suicide attempts. And you see a political consciousness forming; not in terms of political groups, like the Communist Party her parents were part of or the Dalit Panther movement in which Dhasal played a large role, but a tragic, first-hand understanding of where women stand even among ideologues who claim to understand egalitarianism, whose hearts bleed for the poor and marginalised but never for the women in their homes whose physical and emotional labour they demand as their right.

The opening of I Want to Destroy Myself does a very difficult thing: once you’ve read the book and know what follows, it seems all the more incredible because you now understand just how much skin Shaikh, who was in her twenties when the memoir was first published, is peeling away — it’s not a statement by a person defiantly presenting their life before you, and who doesn’t care what you think. It’s by someone laying themselves bare to scrutiny, to judgement, and hopefully to empathy; a person who does appear to care what you think, but who does it anyway, with a purpose:

To confront your life is sometimes easier than opening it in all its nakedness before others. Many famous, successful, capable men have written autobiographies… but does an autobiography really present a person to others? When, as an ordinary woman, I decided to throw open the doors and windows of my life, I knew I might be accused of stupidity or whatever else but sometimes narratives happen so inevitably that it does not even seem to matter whether there is a reader or not. The story takes shape as of itself.

As a woman I seek justice in a patriarchal world. My role is clear to me.

The book’s first half contains delightful descriptions of life with her family and her early childhood, life as the daughter of a legendary performer, and life in the neighbourhood of Saat Rasta, a “museum of humanity”. We learn of how her parents fell in love. Their marriage was opposed not just by their families, but by the Communist Party and its ideals of egalitarianism to which they were so dedicated:

The greatest uproar happened in Aai’s home. But even before that, the Party decided to oppose their marriage. [… T]he Party was not sure that the marriage would work, ideologically.

The objection was that as her mother was an educated, middle-class working woman and her father was only a “final-pass” (Shaikh does not mention if the objection was also because of their different religious backgrounds), the marriage would not work out, and hence cause problems for the Communist Party.

When Shaikh was 12, her father died in an accident and the family’s lives were torn apart. She recounts how her older sister, dealing with the coroner’s court, refused to let them record his religion as anything other than “Humanism”. And we also learn a little about her unconventional mother, referred to through the book as ‘Aai’:

To Aai, cooking was an ordeal. You could never be sure that there’d be something to eat when you were hungry. And if she were reading a book, we could just forget about food. She wasn’t going into the kitchen until she had finished. And then she might just lay the book aside and say, ‘Oh, order some food, please.’

Growing up, their house was a magnet for young intellectuals and Shaikh, still in school, was already known for her intellect and her poetry. Her early encounters with Dhasal, who she says would walk around wearing a necklace of big pearls in those days, give us a sense of what in him attracted her schoolgirl self:

Who did he think he was? Other young men fell all over themselves to talk to me, and this one? I knew he was a poet. I had read Golpitha. I hadn’t understood much of it but in the poems that I had understood, what came across clearly was his power. There was something enigmatic and terrible and magnetic all at once. The poems drew you in. It was as if some carnivorous animal was lurking inside them and its claws would reach out and score your body…

* * *

Golpitha created a storm in the world of Marathi letters. Its elegant outlines, its carefully manicured beauty was wiped out by one Namdeo Dhasal. His words were cruel, savage. They were words that could not be easily understood and yet they felt like an attack. It was difficult to believe in the world they conjured up; it was impossible not to believe in it. Who could write like that? It was as if someone savage had arrived in the secret garden of poetry and was going to uproot all the values we had nurtured.

* * *

As a taxi-driver, Namdeo knew every corner and backstreet of the city as if there were maps in his mind. They would talk about how to make bombs. All this seemed revolutionary and romantic to me. They could talk until two or three in the morning. My job was to keep the tea coming.

At the time, her role as tea-maker doesn’t appear to have struck her as a warning signal, or for that matter, the fact that Dhasal told her, “In a political movement, there is no room for the personal.”

The couple would often go out together, and return late; Shaikh tells us how they would make out at night by the seaside. After all, to a fiery 17-year-old poet like Shaikh, Dhasal “fit in with my ideal: masculine, maverick, sensitive, a poet to love and to love me.” But one of many shocking moments in the book comes when she describes the first time they had sex:

We went home and were sitting together in the room when he asked:

‘Giving?’

‘What?’

‘Your womanhood.’

And before I could answer, he had his hand over my mouth.

Baap re, that first time was nothing but pain. I wondered how anyone could get any joy out of this circus. It hurt so much… But I like surrendering my body to the man I loved. The whole thing was a bit awkward and I discovered that women are much more beautiful than men. Without their clothes on, there’s something a bit repulsive about men.

Exhausted, we fell asleep. There was no pleasure that night for me, only pain.

After the wedding, Dhasal taught her how to cook and keep house, and “looked on appreciatively” while she did so. But amidst all the tea-making and putting up with guests and complete lack of privacy that came with being the wife of a political leader, some of the most startling passages in her memoir are from when she discovered she was pregnant, and went to a hospital for the delivery:

The doctor came along.

‘I want an operation. I can’t bear too much pain.’

She laughed.

‘Why are you frightened? Natural childbirth is the best.’

I could not bear pain. Each contraction now seemed to set my body on fire. It seemed as if the muscles of my waist and hips were being mangled. When each subsided, I would fall into an exhausted sleep until the next pang would rouse me from my half-conscious state. I began to howl. I was surrounded by women close to delivery. They were calmly waiting for the moment of their release. The ayahs would make lewd jokes. Even in that state, I wanted to stick a gun into the mouth of one of them as they mocked the pain of other women.

With a contemptuous laugh, one would say: ‘Now you’re crying. How did it feel when you were taking it in?’ and comments of the sort.

* * *

I lay there, my thighs wide open, my calves splayed. Ward-boys were coming and going but instead of feeling shame, I was only afraid that I might die. If this was supposed to be the height of fulfillment of femininity, I had nothing to say; I only wanted to spit at it. Someone thrust my knees up to my stomach and held them there. They cut me down there. In this symphony of pain, this was a new high note on which the new life pushed its way out. The nurse put it in a tub and showed it to me. It was all red, a raw piece of flesh, the umbilical cord still attached, the birth blood smeared over it. I took one look and blurted out:

‘What is it?’

‘A boy.’

I was disappointed. The nurse was shocked. Here I had got myself a boy on my first time out and I was not over the moon.

* * *

“This is where women come again and again? To undergo this death? My hair stood on end at the thought. This was where they ensured the posterity of their families? Where they first experienced the joy of motherhood? Where femininity reached its apogee?

Yuck.

Should women accept these euphemisms that have been obviously invented by men? Should we not question them? What happiness can a woman find in such suffering? Why should she be lured down familiar paths, paths that lead nowhere? Why must she content herself with fine shining promises that will never be fulfilled? This world terrified me. Even its empty peace had the same quality of hovering between life and death. In that world of sighs and groans, I made up my mind: I was not coming back.

“To write an account as I have is supposed to be an act of shamelessness,” Shaikh writes. But it’s hard not to see it as an act of incredible bravery. She went through three abortions so she would never have another child: birth control pills would make her sick and Dhasal refused to use condoms. He’d come home drunk and she’d avoid sleeping with him, saying “be right back” and going to the bathroom, bolting the door and standing there for an hour or two until he’d fallen asleep.

Shaikh makes no attempt to paint herself as the model partner either:

Some people got together and gave him a sound thrashing. That night, someone threw him into a taxi and dumped him on our doorstep. They had made a thorough job of it. His whole body was swollen, his face black and blue. In the morning, Aai woke me up to tell me.

Angrily I said, ‘Forget it, Aai. Let him die.’

He heard this and got angry. I refused to go and see him. Aai was truly frightened of him. And this angered me too. We had severe fights and I could see that these tormented both of us but I never stopped hurting him. I wanted to take revenge on him, revenge for all that he had done.

And it’s Shaikh’s rejection of both the Dalit Panthers and the Communist Party that is so telling of how women fail to figure in the male imagination of revolutionary movements:

In all the rush and push of political struggle, the question of women’s rights will never be addressed. I know this all too well. For every politician addresses every question only after he makes sure his own rights have been secured. In other words, most progressive men (!) believe that it is up to women to do ‘something or the other’ to empower other women and further the struggle for women’s rights. And this while women are not allowed to leave the house to help other women. Men cannot get beyond women’s bodies. These are the two failures of the movement.

The male ego is the most dangerous and twisted thing in our society. And serving this ego is supposed to be the highest goal of a woman’s life. This seems to be the same thing as the tree in the fable that gives its branch to make an axe for the woodcutter.

My life cannot be made over to anyone, not even Namdeo Dhasal.

“At the end of one’s life, will it be possible for one to look back with courage?” Shaikh writes at the beginning. The book was published a decade after her marriage to Dhasal, before his leaving the Panthers and his support of the Shiv Sena. If he seems to occupy an inordinate amount of space in the book, perhaps it is because it was one of the most consuming things of her life: the marriage didn’t end with the publication of the book. The man she knew as “innocent and foolish and open but a hooligan at heart”, who accused her in turn of being too middle-class to be truly generous, was someone she was never quite able to leave, despite the beatings and the manipulation and the threat of custody battles over their child Ashutosh.

When Dhasal died in 2014, I remember seeing recent photographs of him and Shaikh, with her long hair and interesting fashion sense, and the picture of happiness they presented. But now I’m reminded of an obituary for Dhasal written by Rajvinder Singh. It mentions Shaikh, who he says was “often worried about him.” Singh goes on to say, “But she let him do what he wanted and instead suffered herself.”