AFTER THE WAR

At the end of the war

When the counting of dead bodies

began, the Pandavas and the Kauravas

beat their brows together in horror.

‘Why did we fight at all?’ asked

the Pandavas. ‘How did

they die?’ asked the Kauravas.

‘Whose cruel deed was this?’

enquired the Pandavas. ‘Who

was behind it?’ enquired

the Kauravas. ‘Aren’t we kin?’

Pandavas wondered. ‘Aren’t we

neighbours?’ wondered the Kauravas.

‘Our rivers are the same,’ said

the Pandavas. ‘Our languages

are the same,’ said the Kauravas.

‘Our house was on the

other bank of the river,’

remembered the Pandavas.

‘Ours too,’ echoed the Kauravas.

‘The same earth, the same water,

the same sky. The same food,’

Pandavas sang in a chorus.

‘The same tree, the same blood,

the same pain, the same dream,’

Kauravas took up the refrain.

Then they polished their guns

and began shooting one another.

(Written soon after the Kargil War

between India and Pakistan)

THE MEMORY OF HIROSHIMA

(Written on Hiroshima Day, 1991. Dedicated to the people of Peringom, Kerala, fighting against the proposed nuclear reactor in their village.)

We, grass no storm can break,

survivors of rabbits, earthquakes and revolutions,

silent witnesses to murderous crimes, say:

No more.

1

We remember Hiroshima:

Death descended like the spring in the valley

with the light of a million suns.

Then charcoal, ashes,

an orchard of skulls.

Burnt kimonos dripping

with breastmilk and blood,

the tiny shoes of children

fallen dead on the steps while

rushing back to their homes’ cool shelter,

darling dolls that had leapt down scared

from the schoolbags,

now lying charred on the floor,

fingers that had woven clothes and bread

now stuck to the stilled machines,

the caps of dead songs,

the skirts of dead dances,

liquefied loves,

cherry blossoms dissolved

in the white heat of the scorching summer,

molten eyes,

molten time still on molten clock,

molten language stuck to

molten slates.

2

We grass,

who turn the earth into

a revolving emerald in space,

guard from pain

the feet of the playing children

and the falling flowers,

and tattoo the skulls of the dying

with colourful dreams, say:

No more.

We remember Chernobyl:

Death had come not blood-soaked

like the knife-thrower,

nor in tight vests with a red kerchief

like the bullfighter.

Hiroshima’s sun had risen

like the primal explosion

that had given birth to our earth.

He came amidst the revelries

of that midsummer night in April

to choke the nightingales’ throats,

to still the dancing Gypsy feet.

Invisible serpents of slithering heat,

venomous light piercing the cawing of crows

and the mewing of cats,

children’s life-breath vanishing into

the balloons with the air that blows them up,

mothers carrying their burning children

running all thirst along

streets that lead nowhere,

still-borns delivered on blanched beds

like vain prayers,

milk-bottles brimming with pale death,

tomato-fields that suck human blood,

wheat-fields wielding their golden sword,

stunted trees from which dead birds fall,

bitter honey, black pollen, black snow,

killing shower, killing air,

killing moonlight.

3

We, grass,

the green flags of dreams

stained by the atomic rain,

announcing life’s tenderness

even in the deserts of the battlefield,

did not grow just to be crushed under

the hooves of eternal night.

Lend your ears to our green message:

Wake up, mothers nursing lullabies

and cucumbers in this soil,

with the drums of the minstrels announcing

the dawn for witness,

save from the atomic eclipse

the deathless moon of your selfless love

with its healing roots,

Rise up, brave peasants, rearing

future’s gold in paddy-fields

and grandchildren’s dreams,

with the tears of ancestors

dried up on the ritual masks for witness,

retrieve from the poisoned earth

the untiring sun of your courageous action

that smells of arecanut flowers

until the rhythms of abundant life

echo in the drums of the untouchables

and the hearts of the dispossessed,

until this earth flowers once again

in the melodious rains from the

shepherd’s flute and the monsoon clouds.

THE LAST DREAM

I dream of a day when

jasmine creepers will

wind round tanks,

rifles will support

cucumber vines and

godowns of gunpowder

will fill with the fragrance

of champa flowers

Then pupils will rain,

hands grow feathers,

white clouds turn into angels

and borders disappear

Once again… I… will…

kiss… your… eyelids…

Oh…!

Translated from Malayalam by the poet. K. Satchidanandan is perhaps the most widely translated and anthologized of contemporary Indian poets. His books in English translation are While I Write: New and Selected Poems (2011), Misplaced Objects and Other Poems (2014) and The Missing Rib (2016). In 2015 he resigned all his positions in the Akademi to protest rising intolerance and attacks on artists and writers; read his letter to the Akademi here. You can also read his essays on the ICF site here, and his poems and translations in Guftugu here.

These poems are the sixth in ICF’s unfolding Citizens against War series of literature and art, initiated in the spirit of listening: to our poets, artists, fellow citizens, against war and warmongering.

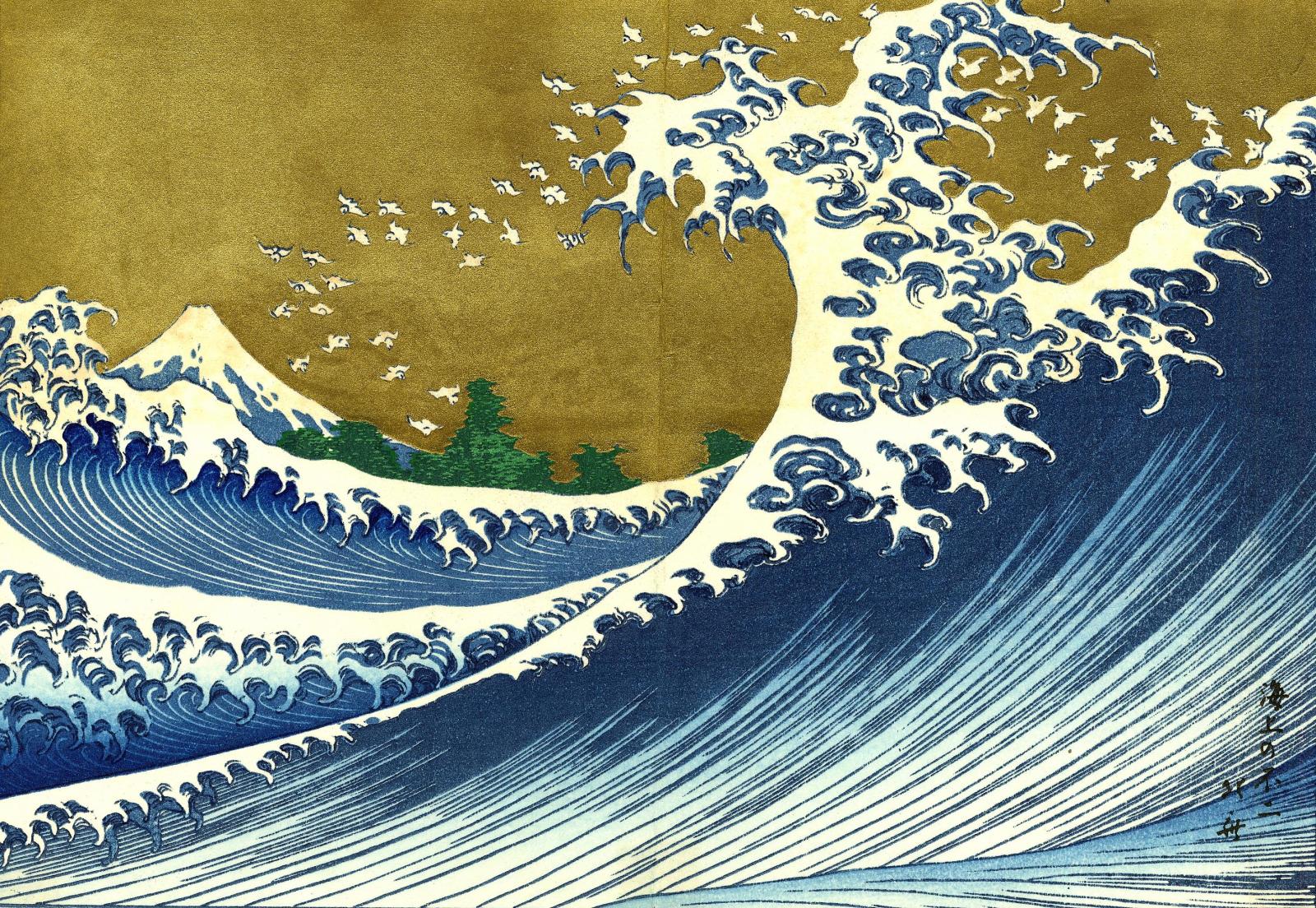

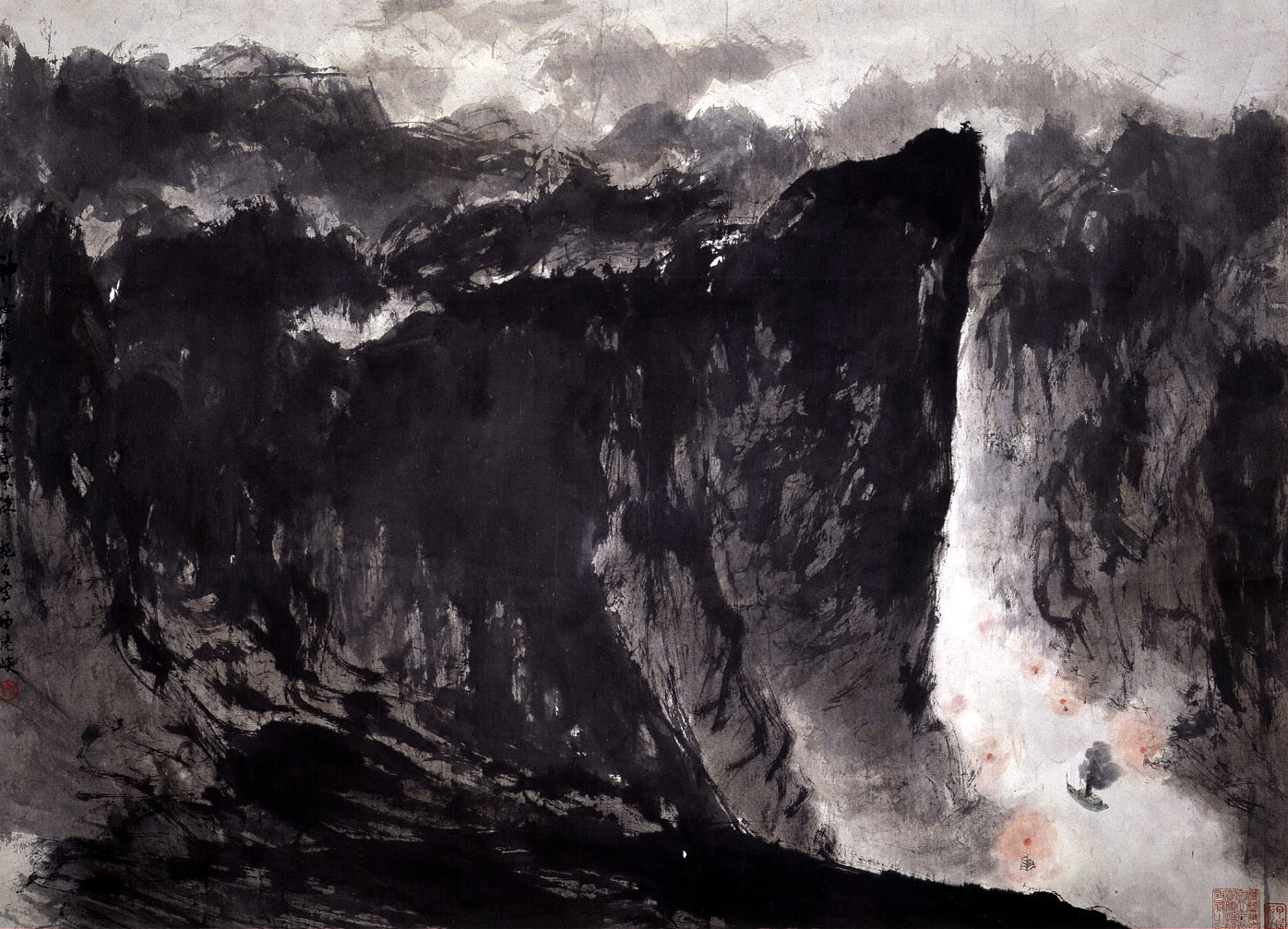

Text © K. Satchidandan. Images from top: © Fu Baoshi / Pinterest ; Yamamoto Baiitsu / Plathey ; Katsushika Hokusai / Althouse ; © Fu Baoshi / WikiArt.