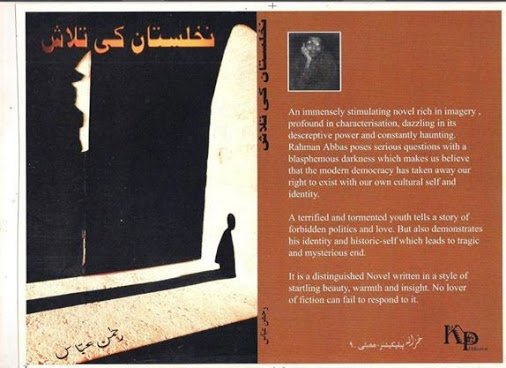

Nakhlistaan ki Talash / Sourced from Google

On 19 August 2016, a lower court in Mumbai delivered a judgment on a ten-year-old case against the Urdu novel Nakhlistan ki Talash (In Search of an Oasis). The novel and its author, Rahman Abbas, were acquitted of obscenity charges made under the colonial-era Section 292 (sale of obscene books) of the Indian Penal Code. Abbas feels free today, and vindicated, and so do all readers and writers. But he spent ten years searching for an oasis without regressive, outdated laws, where writers and readers can do what they must without supervision by the thought police.

The book, a romance set in Mumbai after the 1992-93 riots, takes on two themes Rahman Abbas has returned to time and again: love and politics. In 2005, a nineteen year old Mumbai student lodged a complaint against the novel, objecting that two paragraphs in it were “objectionable and obscene”. The publisher, distributor and author were charged. The police went to the author’s home to arrest him. He spent a night in jail; the allegation cost him his job as a school teacher. It also brought him vilification from fundamentalists and sections of the Urdu media for questioning “religion” and “the existence of God”.

Abbas has written three other novels: Ek Mamnua Muhabbat ki Kahani (A Forbidden Love Story); Khuda ke Saaye mein Ankh Micholi (Hide and Seek in the Shadow of God), which won the Maharashtra State Sahitya Akademi award; and the more recent Rohzin (The Melancholy of the Soul). In 2015 he returned his Sahitya Akademi award, saying “…we cannot remain voiceless… I request senior Urdu writers, poets and critics… to register a protest against the murder and killing of creative writers”.

ICF spoke to Rahman Abbas about his plans to fight Section 292, and an artist’s space for probing the two equally important themes of politics and love.

Obscenity is such a subjective charge that it becomes almost arbitrary. What exactly in the novel was considered “obscene” and “objectionable”?

Let us begin with the fact that the concept of obscenity didn’t exist in the history of Indian civilisation and thought. It is a byproduct of foreign faiths which invaded and ruled over India for the last few centuries. Till as late as the Mughal era our paintings and other forms of art have celebrated nudity, love and sexuality as a medium for experiencing divine conciousness. The British rulers, under the tremendous influence of religion, forced the concept of obscenity upon Indian society. Interestingly, the United Kingdom abolished Section 292 a century ago now, but it has remained stuck inside our constitution. As far as objections to my novel are concerned, they related to sections in which the protagonist recalls how madly in love he once was, and a surrealistic dream in which he imagines a persona – very similar to his beloved – which makes love to him.

Your victimisation by fundamentalists and conservatives in the Urdu media brings to mind the experience of the Angarey writers. Do you see a continuous struggle of the writer to hold on to a space for questions and dissent – first within his or her own community/ language, then the larger one? How do these two spaces interact?

A large section of the Urdu print media in India is in the wrong hands, and hence as orthodox as it was a century ago. In fact now it has become more intolerant, under the influence of the rise of fascists in Afghanistan and other Middle Eastern countries. Ours is a time when some Urdu newspapers are even using a narrow version of religion to provoke their readers to take the law into their own hands, especially in connection with blasphemy allegations. However, the Urdu language and its writers are as progressive as they were when the modern progressive movement in the sub-continent was getting underway. Or indeed, as progressive as they were in the times of Mir Taqi Mir and Ghalib.

The history of Urdu literature is a history of liberal human traditions which celebrate life without giving any importance to religious thoughts or sentiments. In fact Urdu poetry laughs at the orthodox religious mindset. The struggle to question and dissent continues till today; sadly, in Urdu, this space has narrowed. In Urdu one cannot question religious orthodoxy or criticise organizations using religion as camouflage. But the same scenario is visible at the national level, where the space for dissent is unfortunately invisible. If that space were there, activist and thinker Narendra Dabolkar, Prof. Govind Pansare and Prof. M.M. Kalburgi would have not been killed. It is very difficult nowadays to question the policies of political parties, or the activities of hate mongering organisations which are using Hinduism for political gain, at the cost of destroying a plural Indian civilisation and our mutual coexistence.

You have said we must fight the outdated Section 292 we got from the British, who have since dropped it. How do you plan to do this?

Section 292 is the result of religious influence in law-making in India. The UK, USA and many European countries have abolished or amended equivalent laws. Creative writing, painting and other forms of creative expression have been omitted from its purview. I wish to garner support from Indian writers to move against this article: if we all come together and file a petition in the Supreme Court, I think we will find a way to get rid of this draconian law.

We have newer manifestations of the thought police today, besides Section 292. Would you comment on this, especially in light of your returning your Sahitya Akademi award in 2015, and the National Council for the Promotion of the Urdu Language (NCPUL) form Urdu writers were required to fill?

“Thought policing” is a dismal human condition and an abuse of privacy. Government regimes, politicians and authoritarian rulers desire it so they may prolong their hegemony and tyranny. It can be well understood in the context of the charges of “sedition” framed by imperialist forces in India and other colonies; or by our government in recent times. I returned my State Sahitya Academy Award in 2015 as a token of protest against the continued silence and inertia of the government when Hindutvadi fascist forces were murdering our intellectuals and writers. Moreover, these organisations brutally murdered Muhammad Akhlaq in Dadri over allegations that he had eaten beef. They are like a Hindu Taliban: but then we saw that the local administration and central government long took no action against the murderers. In this situation, by returning their awards senior writers showed us one way we could voice our concern about politically manufactured hatred such as this. I was part of that movement, and continue to be.

The NCPUL issue is quite different. Under the chairmanship of Irteza Karim the Council introduced a form which essentially forced writers not to criticise any government policy, failing which their books would not be purchased under an NCPUL scheme. The issue was brought to light by Prof. Shahnaz Nabi, head of the Calcutta University Urdu department, writer Abrar Mojeeb and novelist Yaqoob Yawar. I raised the matter with friends working in English newspapers, after which support poured in from every corner of the nation. The issue was finally raised in parliament, and the government had to withdraw this unconstitutional and anti-people form.