Bhagat Singh was hanged to death on March 23, 1931, in Lahore. We reproduce here two articles, “Bhagat Singh” by Periyar E.V. Ramasamy, first published on March 29 that year, and “Three Victims”, an editorial by B.R. Ambedkar published on April 13, 1931.

![]()

Jackson Pollock / MoMA

Jackson Pollock / MoMA

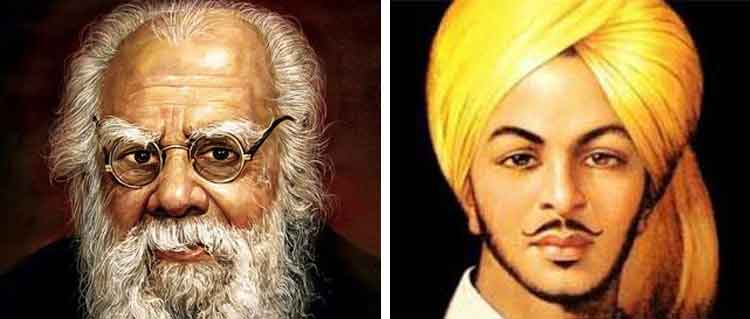

Bhagat Singh

Periyar E.V. Ramasamy

Editorial in Periyar’s journal Kudi Arasu, March 29 1931

Translated by V. Geetha and S.V. Rajadurai

There is hardly anyone that has not expressed sorrow at the hanging of Bhagat Singh. Nor is there anyone who has not condemned government for thus sending him to the gallows. Meanwhile, we are witness to the so-called patriots and nationalists blaming Gandhi (for Bhagat Singh’s death—translators). This, on the one hand. On the other hand, we see the same set of people (self-styled patriots and nationalists—translators) congratulating Mr. Irwin, the head of government, and praising Gandhi for agreeing to hold talks with Mr. Irwin; and expressing their satisfaction at, and celebrating as a victory, a pact that does not include the condition that Bhagat Singh ought not to hang. In addition, we are witness to Gandhi hailing Lord Irwin as a Mahatma and and exhorting the people of this country to do the same; and we also have Lord Irwin referring to Gandhi as a great soul and a divine sort of person, and ensuring that this fact is advertised widely among the English.

But very soon, the same people raised slogans such as ‘Down with Gandhism’, ‘Down with Congress’ and ‘Down with Gandhi’ and it is now quite common to greet Gandhi with black flags wherever he goes, and cause confusion in the meetings he addresses.

Considering all this, we are unable to understand what opinion the general public has with regard to political matters, and if, indeed, they possess any principles. We are inclined to suspect that they possess none. However this may be, since the day Gandhi launched his Salt Satyagraha, we had pointed out that this agitation would benefit neither the people nor the nation, and that it might actually be detrimental to the nation’s progress and to the cause of the people’s freedom. It is not only us, but Mr. Gandhi himself who had clearly and explicitly said that his agitation was intended to impede and destroy the activities of Bhagat Singh and his kind. In addition to this, true socialists and patriots in neighbouring countries have been crying sky-high that ‘Mr. Gandhi has betrayed the poor, his activities are meant to do away with socialist ideals, and so Mr. Gandhi must go, and Congress must go.’ But our so-called patriots and nationalists, unmindful of anything and without paying heed to the consequences, were elated and danced around—not unlike those who fall into a well, even while holding a lit lamp; or those who, for a wager, do not mind striking their head against a rock. And as a result, they went to prison and when released, came back with ‘victory garlands’ around their necks. They are puffed with pride on this account. Yet, now, after seeing Bhagat Singh hanged, they clamour, ‘down with Gandhi’, ‘down with Congress’ and ‘let Gandhi perish’. We do not understand what is the purpose of all this.

To tell the truth, in a country where we have idiotic, foolish and irresponsible people, and those guided by self-interest and concerned with their own glory, people who are unmindful of the consequences of their actions, it seems to us that it was better for Bhagat Singh to have laid down his life and rested himself in ‘peace’ rather than live long and witness their actions, be impeded by them, and suffer agony on their account every succeeding moment. We only regret we are not endowed with such a fortune.

For the question really is this: has a person fulfilled his duty or not? We are not concerned here with the results. We accept that dutiful action has to heed time and place, but we hold that as far as the principles that Bhagat Singh lived by were concerned, these were not contrary to the claims of place, time and action. It might appear to us that, perhaps, the method he chose to realise his ideals was somewhat at fault, but yet, we would never dare to fault the ideals themselves. For his ideal was world peace.

If Bhagat Singh has indeed acted out of heartfelt conviction, in his ideals and also in the path he chose to walk which would help him realise them in practice, we cannot but appreciate his courageous act; and in fact we make bold to say that had he failed to walk his chosen path he could hardly be called an honourable man. But now we proclaim that he was an honest man. We strongly believe that Bhagat Singh’s ideals are what India needs—as far as we know, he believed in the ideals of Samadharma and Communism. This is evident in these sentences which feature in a letter he wrote to the Governor of Punjab: ‘Our battle will continue till the Communist Party acquires power and the disparities between people—in their status—are done away with. This battle will not cease—just because we are killed. It will contiue, openly and clandestinely.’

Moreover, we are also aware that he was a man who did not believe in God, or that things are willed by God. We believe that it cannot be considered a crime in law to hold such a principle, and that even if it were deemed a crime, no one needs to be afraid of it. Because we strongly believe such a principle does no harm to the people; nor does it deprive them of anything. If by chance, there is a possibility that this principle may cause harm to the people, we would consciously strive to realise this ideal, without bearing hatred towards any particular individual or caste or nation, and without causing physical pain to any particular individual’s person; we would, at the same time, not mind subjecting ourselves to pain and suffering, and in a sacrificial spirit, we would do all to realise this ideal in practice. So no one need be worried or afraid.

The philosophy that desires to end poverty is akin to the philosophy that wishes to abolish untouchability. Just as notions of high and low [castes] have to be abolished for untouchability to be destroyed, for the abolition of poverty, notions that divide society into capitalists and labourers must be done away with. These are precisely the ideals of Samadharma and Communism, the ideals of Bhagat Singh, and it is not surprising that one who considers these just and essential ideals naturally enough condemns the Congress and Gandhism. But, we are surprised to find those who subscribe to these ideals proclaim ‘Long Live Gandhi’, ‘Long Live Congress’…. The moment Gandhi claimed he was guided by God, that varnashrama dharma was superior to the way of the world, and that everything happened on account of divine will, we concluded that there was no difference between Gandhism and brahminism: and unless the Congress, which is charged with this philosophy, is abolished, no benefit would accrue to this country. Only now have some of our people realised the truth of our understanding, and acquired the knowledge and courage to denounce Gandhism. This is a great victory for our creed.

If Bhagat Singh had not been hanged, if he had not sacrificed his life, there could not have been any basis for achieving such a glorious victory (for our creed). If Bhagat Singh had not been hanged, Gandhism would have acquired greater glory. A life that, in the normal course of things, would have ended and been reduced to mere ashes, on account of illness and suffering has been ended instead in a manner that proved useful in showing the people of this world the path for realising true equality and peace. Bhagat Singh has attained an exalted state, which no ordinary mortal can easily achieve. Therefore we praise him, whole-heartedly, with all that our tongue is capable of and with raised hands. In this context, we appeal to the government to identify persons with similar courage of conviction and hang at least four persons every month in each of the provinces.

Image: Countercurrents

Three Victims

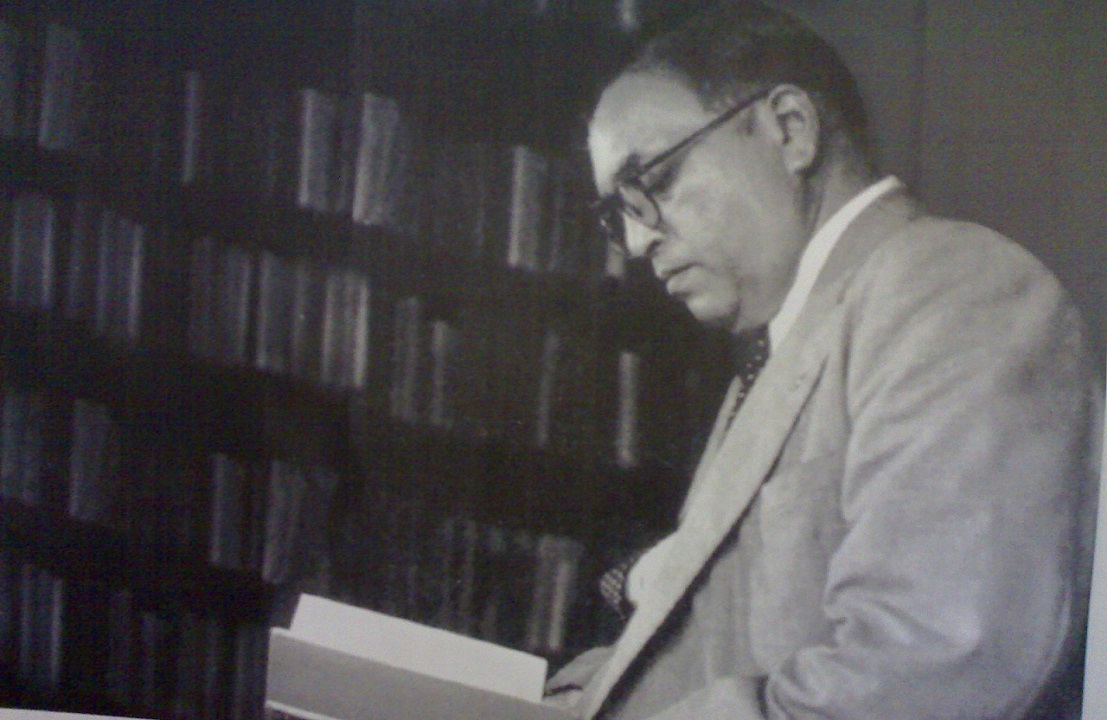

B.R. Ambedkar

Editorial in Janata, April 13 1931

Translated by Anand Teltumbde

Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru have eventually been hanged. They were charged for the murders of an English police officer named Sanders and a Sikh police sepoy named Chaman Singh. There were three or four additional charges, such as an attempt to murder a police inspector at Banaras, throwing a bomb in the Assembly, and conducting a robbery at a house in Maulimiya village and looting its valuables. Bhagatsingh had already admitted to the charges of throwing bomb in the Assembly. For this crime, he and Batukeshwar Dutt had already been sentenced to life imprisonment. One of Bhagatsingh’s comrades, Jaigopal by name, had confessed that Sanders’ murder was executed by the revolutionaries, including Bhagatsingh, and others. The government had filed a case against Bhagatsingh and his comrades based on this confession. None of the three accused participated in this case, however. A special tribunal comprising three high court judges was appointed which heard the case and unanimously awarded them the death penalty.

Bhagatsingh’s father had made a mercy petition to the Emperor and the Viceroy, requesting them not to execute the punishment, and to convert it if required into life imprisonment at Andaman. Many people including prominent leaders also tried to plead with the government in the matter. The issue of Bhagatsingh’s death penalty might have arisen in negotiations that took place between Gandhi and Lord Irwin. Although Lord Irwin had not given any definitive assurance about saving Bhagatsingh’s life, Gandhi’s speech during the intervening period created a hope that Irwin would try his best, within his powers, to save the lives of these three youth. But all these hopes, predictions and appeals proved futile. They were killed by hanging in the Central Prison, Lahore on 23 March 1931 at 7 p.m. None of them made any appeal to be saved. But, as has already been published, Bhagatsingh expressed the wish to be killed with bullet shots instead of being hanged by the neck. But even this last will of his was not granted, and they implemented the judgment of the tribunal verbatim. The judgement was to hang them by the neck till dead. If they had been killed with bullet shots, the execution would not have conformed to the judgement verbatim. The order of the justice-goddess was obeyed in toto, and the three were killed with the method she prescribed.

For Whom the Sacrifice?

If the government thinks that the people will be impressed by its display of devotion and strict obedience to the justice-goddess, and that therefore they would approve of this killing, it would be its utter naiveté. No one believes that this sacrifice was made only with the intention of maintaining the clean and sans-blemish reputation of the British justice system. Even the government will not be able to convince itself of such an understanding. Then how will it convince others with this veil of the justice-goddess? The entire world, as well as the government, knows that it is not because of devotion to the justice-goddess, but fear of the Conservative Party and public opinion back home in England, that this sacrifice was executed. They thought the unconditional release of political prisoners like Gandhi, and signing pacts with Gandhi’s party, has damaged the prestige of the Empire. Some orthodox leaders of the Conservative Party have launched a campaign alleging that the prevailing cabinet of the Labour Party and the Viceroy who danced to its tune were responsible for it. In such a situation, if Lord Irwin had shown mercy to political revolutionaries who have been convicted for assassinating an English officer, it would be like giving a burning torch into the hands of opposition leaders. As it is, the condition of the Labour Party is not stable. In such a situation, if these Conservative leaders were able to say that the Labour government grants clemency to convicts who murdered an Englishman, it would be so easy to provoke public opinion against it. In order to avert this imminent crisis, and to thwart the fire in the minds of conservative leaders from flaring further, these hangings were executed.

As such, this was not to satisfy the justice-goddess, but to please public opinion in England. If it had been a question of Lord Irwin’s personal likes and dislikes, he could have within his own powers annulled the death penalty and awarded life imprisonment in its stead. The cabinet of the Labour Party in England would have supported Lord Irwin in this decision. It would have been necessary to maintain congeniality of public opinion in the context of the Gandhi-Irwin pact. While leaving the country, Lord Irwin would surely have liked to earn this goodwill. But he would have been crushed: between the ire of his Conservative kin in England, and the Indian bureaucracy which is imbued with the same casteist attitude. Therefore, unmindful of public opinion here, the government of Lord Irwin hanged Bhagatsingh and his comrades to death, and that too just two to four days before the Karachi Conference of the Congress. Both, the hanging of Bhagatsingh and his comrades, and its timing, were sufficient to puncture the Gandhi-Irwin pact and to trash all efforts to bring it about. If Lord Irwin wanted to sabotage this pact, he could not have found a better means than this. Looking at it from this perspective, which Gandhiji also felt, one could say that the government committed a great blunder.

In sum, in order merely not to incur the anger of the Conservatives in England, they sacrificed Bhagatsingh and his comrades, ignoring public opinion and not minding what would happen to the Gandhi-Irwin pact. The government must remember, howsoever it tries to cover it up or polish it; it will never be able to hide this fact.

![]()

Translations first published in Countercurrents.