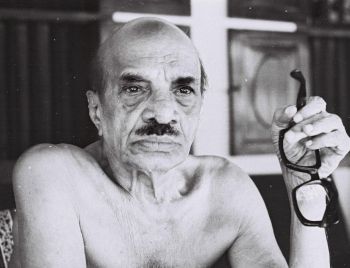

K Satchidanandan

Photo courtesy http://onlinestore.dcbooks.com/author/vaikom-muhammad-basheer

Photo courtesy http://onlinestore.dcbooks.com/author/vaikom-muhammad-basheer

Vaikom Mohammed Basheer (1908-1994) belongs to the democratic tradition in Indian literature, a living tradition that can be traced back to the Indian tribal lore including the Vedas and the folktales and fables collected in Somdeva’s Panchatantra and Kathasaritsagara, Gunadhya’s Brihatkatha, Kshemendra’s Brihatkathamanjari, the Vasudeva Hindi and the Jatakas. This tradition was further enriched by the epics, especially Ramayana and Mahabharata that combined several legends from the oral tradition, and are found in hundreds of oral, performed and written versions across the nation that interpret the tales from different perspectives.

The need to renegotiate the nation was obvious to the generation to which Basheer belonged. Despite being born out of our colonial encounter, fiction in India had its roots in our own narrative tradition and has been since its origins attempted to narrate the Indian nation in all its plural complexity. The novels, and to a lesser extent the short stories, written before and after Independence, reveal to us the various ways in which the Indian nation was imagined and re-imagined. Together, they can be said to constitute an unofficial history of the subcontinent. We may recall that unlike in Europe where fiction was made possible by the autonomous sensibility of an individuated consciousness that came into being in the 18th and 19th centuries, such a state had not been achieved in India when the novel and the short story were made available as a ready-made form. As a result, the Indian fiction writers were able to put into productive use the prevailing modes of native story-telling traditions, as well as the narrative mode of the epic. Our early novels like Bankim Chandra’s Anandamath, Govardhanram Tripathi’s Saraswatichandra or O Chandu Menon’s Indulekha, were constituted to serve the emerging middle-class nationalistic ideology. This led to much exclusion and distortions that came to be interrogated by writers like Premchand and others. Their attempt to construct an alternative national consciousness was also prompted by a predatory element in nationalist ideology that had begun to manifest itself in Germany and Italy in the form of Nazi and Fascist practices of exclusion. It had a negative and insular definition of the nation achieved through planned genocide. The Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtreeya Swayamsevak Sangh had also begun to exhibit these tendencies that would grow to fatal proportions in indepenedent India. B. R. Ambedkar’s impact was one factor that made Premchand seek alternate locations for narrating the nation. We now know that there were dalit narratives in the nineteenth century like Saraswteevijayam by Pothery Kunhambu in Malayalam that looked at society and history from a totally different point of view.

Basheer looked at life with detachment. While representing the life of the Muslim minority in Kerala and speaking from the outskirts of mainstream historiography, also succeeded in communicating the universal values of compassion, forgiving, tolerance and love, a feat that Manto had established with the same elan. Basheer often calls himself “the humble historian” (“vineetha charitrakaran”) and this figure of the historian is implicit in his early stories that deal with the issues of freedom and the nation as well as in his later narratives of domesticity. Here, history often assumes the dimensions of parody and mock history.

One such questioning of the nation can be seen in Basher’s short story on prison life, Mathilukal (Walls). It is also the basis of a rare film by Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Basheer himself had spent time in a prison at Kollam. In fact, most of his writings can be traced back to specific instances in his life. Here is a man, Basheer himself, taken prisoner. He has been there so many times that now he is just a number. At one level, the story can be read as a criticism of our prison system with its corruption and discrimination among the prisoners, but the central theme is desire. One day our prisoner hears the laughter of a woman from behind the huge wall. It was from the women’s ward. Her scent fills him with desire. Another day he hears her whistling. They strike up a conversation. Gradually, they get acquainted with each other. Her name is Narayani. They describe themselves so that they could visualise each other. She starts throwing twigs in the air to let him know she is there beyond the wall. He prepares a rose garden on his side of the wall. They also exchange gifts, throwing them over the wall. Once a prisoner had made a hole in the wall, but the warders had found it out and closed it. The two now decide to meet in the hospital the following Thursday. They give each other their marks of identification: she had a black mole on her right cheek, and he was a little bald and would carry a red rose in his hand. But on Wednesday, Basheer gets the release order. His first reaction is, “But who wants freedom?” As he goes out he sees a dry twig rising in the air. He can only pray for Narayani. The story is replete with the contrast between spaces inside and outside, the fragmented space within the walls and the expanse beyond, symbolising freedom. By a reversal of logic, the prison becomes the free space illumined by the woman’s fragrance, the flower flung into the air, her tempting laughter and snatches of their conversation choking with passion. At the end of the story, the protagonist finds it difficult to move into the ordinary space of freedom.

Basheer was one with the Progressive writers in empathising with the hapless and in upholding hope in man and the possibility of change, but he went beyond them while looking at the human condition in its many hues and dimensions, including the spiritual. He belonged to a generation fed on rigid ideologies and arid experiences, but he picked up his tales from the warmth of life’s poetry. During about half-a century of his creative career, he published only thirty books from Balyakalasakhi (1944) to Sinkidimungan (1991) but every one of these 2,200 pages was world class literature. Having abandoned English in which he had attempted his first novel, he created his own language within the language he inherited. Basheer has contributed several usages to Malayalam: meaningless expressions like “huttina halitta luthappee” (something like “humpty-dumpty”); “Kukruma dharma” ( in the context meaning some evil doing), “romamatangal”; (“hair-religions”, pointing to the importance hair has in various religions and rituals); “he-cow” (for ox); “selfichi” (feminine for the self); and “Sinkidimungan” (a hefty person), not to speak of the compound adjectives he uses for women, God and the universe.

Basheer was a modernist who perhaps never knew he was one. He broke new grounds quite casually without being self-conscious. He just recounted his varied experiences of the world in his own crisp and inimitable style. He shunned the big canvas. What mattered to him was the sheer depth and intensity of the narrated event. He hated none; thieves, gamblers, homosexuals, pimps, prostitutes: everyone had a seat in Basheer’s heaven. The fallen, he knew, were the victims of unkind circumstances. They are also the chosen in his world illuminated by the beams of love from the other side of material life.

K. Satchidanandan is a poet and translator writing in Malayalam. Read his poems and translations in the first two issues of Guftugu here.