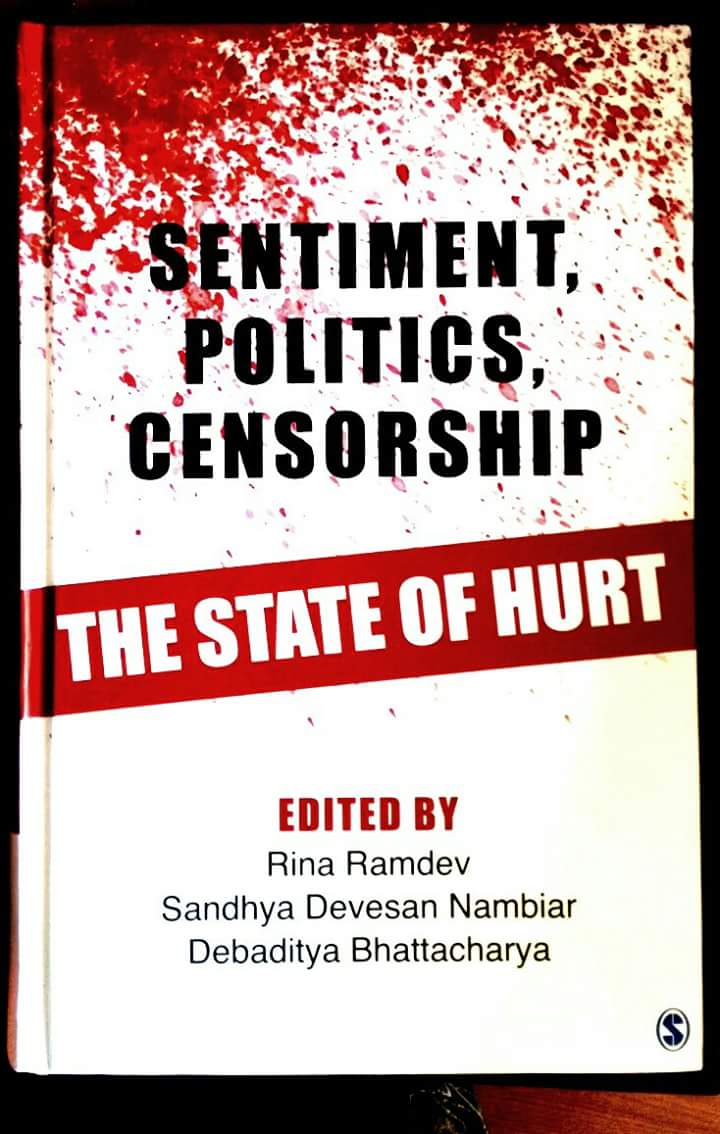

In times when censorship is justified on grounds of hurting “Indian traditions” and “Indian culture”, the Indian Writers’ Forum is proud to present an excerpt from a book that critically engages with this state of hurt. It is a book that attempts to continue the debate on censorship, “but with a purpose to nuance it within a sensory distribution of ‘sentiment’.”

The State of Hurt

To introduce a volume on the place of ‘hurt’ in the formation of the contemporary political subject, one might do well to invoke the supposed self-evidence of ‘commonsense’. Because, it is precisely in a perceived threat to the shared ‘common’ of commonsense that hurt is articulated as a malady, requiring remedial forms of control and regulation over the sphere of the ‘sensible’. Going by the populist variety of opinion in the public media, it is a commonsensical axiom that if there is one species of civic beings that is worse than “politicians” (oh-that-horrible-race-of-the-corrupt!), it is most certainly the shrill full-time professionals of protest in the “activists”. Among activists too, there are obvious hierarchies of condemnation within which to slot the many varieties of them. By all means, climate-change activists today are most likely to be tolerated, while those committed to human rights are safely believed to deserve whole-scale deportation into some such Nazi marvel like the concentration camp! Those protesting censorship by the state or law have in particular been deemed equally despicable – and have therefore earned themselves an interesting term of abuse in current-day media discourses: “free speech advocates”! What effectively gets elided in such name-calling projects is the very nuance of the censorship debate: does a “free-speech activist” champion the constitutional rights of a Kamlesh Tiwari, whose wayward remarks about Prophet Muhammad were calculated to produce communal unrest and the eventual conflagrations in Kaliachak or Purnia? In other words, must the “free-speech activist” equate Dadri with Kaliachak, as the ‘whataboutery’ critics demand? In all of this retaliatory free-play of hurt-claims between Azam Khans and Kamlesh Tiwaris, must the “free-speech activist” ignore as ‘commonsense’ the normalisation of shame and violence as fit responses to homosexuality? Does the “free-speech activist”, consigned by collective conscience to a politics of dissent-as-‘troublemaking’, argue for the rights of a Yo Yo Honey Singh or of the Muslim clerics who proclaim women to be child-bearing equipment? It is here that our book Sentiment, Politics, Censorship: The State of Hurt hoped to pitch in — not for the sake of merely continuing the debate on censorship, but with a purpose to nuance it within a sensory distribution of ‘sentiment’.

The state of hurt as an event and its conflictual articulations by groups, both through volatile emotions and concomitant calls for reparation, has had a long, interminable history. Within its playing of patterns of offence and counter mobilization, no single moment can be deemed as more crucial than the previous or the next. And yet contemporary contexts seem to reveal sudden outpourings of ritualised provocations and subsequent feelings of moral outrage in more than quick episodic continuity now. In our book, we sought an understanding of the moment of hurt, through the sentiment that charges it and also the politics of outrage and its hyper-visibilisation now, more than ever before. By questioning our own claim to contemporary relevance and topicality as a productive entry-point into the debate, we look at the enactment of hurt and its emotive entanglements within disputed claims. This is through an exploration of the ideological content and methods used by those who enact and assert claims of hurt, while paying attention to the uses and meanings of values that are both shared and disputed by them and their identified aggressors.

Couched in the language of hurt sentiments, culture and community, we are witnessing the forces of polarisation accelerate dangerously into free fall. What the triumphalist Hindu Right termed as “award-waapsi” by artists and academics, while pushing the debate on intolerance further, has not taken the barbs off the rhetorical menace of hegemony and cultural homogenisation implicit in slogans like “Ek Bharat”, vigilante-projects like “Gau Raksha Abhiyan”, or the hint of ethnic cleansing within schemes like “Swachh Bharat Mission”. We have also seen this in the de-recognition of the Ambedkar-Periyar Study Circle at IIT Madras for “creating hatred (sic) among the students”, the beef ban in Maharashtra and the bans ordered by the Central Board of Film Certification on “provocative” content. College teachers have atmosphere been charged with sedition for exam questions on the Kashmir struggle; intellectuals threatened with deportation to Pakistan for expressing as much as an opinion about a prime ministerial candidate; writers forced into an announcement of their death as creative artists; social media users indicted for purported acts of irreverence; movie posters/theatres vandalised for screening ‘obscene’ or ‘blasphemous’ films; college drama societies warned of bans for nurturing disaffection against ruling parties and even parliamentarians mandating a loyalty-test by ordering the drowning of those opposed to certain practices of yoga. Such micro-fascist politics is becoming increasingly routinised through manufactured spectres of demonised others, forever looming large on the politico-emotional landscape.

But, how do we treat the question of censorship after a Honey Singh? Do we protect the right to free speech, or we attempt to cease gender violence in public discourse? Does an outrage-prone economy of feeling, through its mediatised projections of collective ‘hurt’ in the Jyoti Singh rape, legitimise the alarm around juvenile delinquency and its sudden urgency in legislative discourses while letting us remain largely complacent about the invisible processes of socialisation that translate into a ‘rape culture’?

Does the contempt proceeding against Arundhati Roy for seeking the release of a disabled university professor — in grossly conflating criticism of the state with the law’s perception of ‘hurt’ — deem constitutional rights as running counter to the administration of justice? Does it not further lend credence to a politics of sentiment manoeuvred by the state to justify its onslaughts of censorship?

If a discussion on the politics of hurt seems most pertinent now, how would one understand the place of ‘sentiment’ in our political past? If our current understandings of ‘hurt’ as constitutive of the limits of political well-being have their roots in a postcolonial moment of identity-articulation, how would one understand the use of sentiment in colonial and pre-colonial formations? Its proliferating currency, however, assumes an increasing incidence of ‘hurt’ over successive periods in history.

This also brought us to the question of the materiality of “hurt” as a felt sentiment, with its own taxonomies of affect. When and how does a politics of consensus make way for apprehensions of fear and pain? What is the place of such emotions of endangerment within a progressive tradition of materialist politics? While this feeling of “being wronged” can be historically evidenced in sustained events of attack on minority-communities and alter-publics, how has the positivist regime of Law been activated by an otherwise pure realm of potentiality?

In bringing sentiment within the empirical-juridical notions of “truth”-as-evidence, is there an attempt to contain its excesses – or, is it only a benign constitutional mechanism to protect the alter-subject’s democratic right to citizenship? Does censorship safeguard alterity, or prevent the proliferation of it through checks and curbs on the right to difference and dissent? Is the censored object necessarily withdrawn from circuits of reception, or does it in turn produce a renewed engagement with the same?

To turn attention to the letter of law, IPC Section 295A — which has veritably become the litmus-test for any community’s claim to collective determination — states:

“Whoever, with deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings of any class of citizens of India, by words, either spoken or written, or by signs or by visible representations, or otherwise insults or attempts to insult the religion or the religious beliefs of that class, shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to three years, or with fine, or with both.”

The litany of terms such as “deliberate,” “malicious,” “intention,” “outraging,” “religious feelings,” “insult,” and “beliefs of that class” inserts a calculated ambiguity in the possible interpretations of this section. One could reasonably ask: how could a work of professional history-writing hope to pass itself off as ‘indeliberate’ and ‘unintentional’ to avoid attracting penalty under IPC? Is all work of history therefore—given the arduous process of ‘deliberation’ and ‘intention’ that necessarily precedes it—liable to be convicted of ‘malice’? It is also worth noting that not all of the same “class of citizens” might necessarily share the same “feelings” or “beliefs.” How many then must share a feeling for it to be ‘outraged’ or ‘insulted’? To assume a numerical consensus within a community of “feeling” would amount to a breach of legal positivism, though it is here that Indian blasphemy laws meet a crucial disjunction.

The twin words—“or otherwise”—in the Code, hinting at the potential innumerability of the means of offence, are significant. They point at the moment of the aporetic at the heart of law, the scourge of the indefinable that functions as the internal logic of law. Though the letter of law is the mark of the limit, its jurisdiction is a limitless possibility. The element of deliberate ambiguity within its own self-definition tames every exception into a state of emergency and a call unto itself. The words—“or otherwise”— open up an infinite space of the criminal-as-possible and never exhaustible within the letter of the law. What is not named can also and at any time be construed and contained within the ambit of its jurisdiction.

Given that censorship has paraded within different domains of social-cultural production under different names of the ‘obscene’, the ‘hurtful’, the ‘harmful’, we have attempted to exhume the historical debates around each. If ‘hurt’ is only another analogue for negative determinations of political affect, what gives it the relevance worthy of a current debate?

We embarked on this course with the idea of scrutinising these unsettled and unsettling claims of political crisis, presenting a bio-political array of sentimental impediments to nativised and narrativised belongings. Such an exercise in the cartography of hurt sentiments and the politics thereof is what is explored in our book – the attempt to chart the fluid pluralities of identities and the multiple structurations of calculated subjectivities that are buried, exhumed and “moulted” within these assemblages of identity, emotion and politics. We hope that the very range, quality and depth of the essays comprising this volume shall make explicit the many traces and inquiries into the organization of the politically abject subject.

From Sentiment, Politics, Censorship: The State of Hurt, edited by Rina Ramdev, Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Debaditya Bhattacharya, SAGE India, New Delhi, 2015.