Sudhanva Deshpande

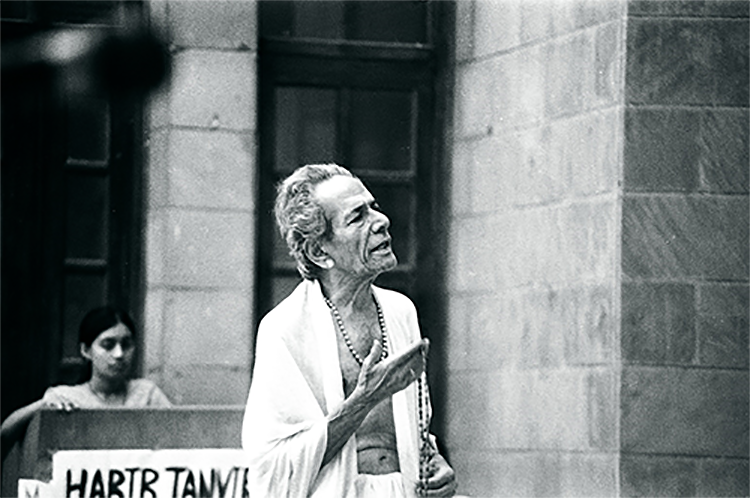

Habib Tanvir as the Rajpurohit in his signature play, Charandas Chor, Modinagar, Rajasthan, October 2002. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande.

Habib Tanvir as the Rajpurohit in his signature play, Charandas Chor, Modinagar, Rajasthan, October 2002. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande.

Habib Tanvir (1923-2009), India’s pre-eminent theatre personality, is inextricably linked with Naya Theatre, the theatre company he founded in 1959 with his wife Moneeka Misra Tanvir. His career was characterised by astonishing output and creativity; in sixty-odd years, he was a playwright, director, actor, singer, poet, designer, manager, teacher and visionary. He was also a public intellectual who responded to his times, not only with his plays, but also by writing, speaking, and participating in protests.

The Early Years

Christened Habib Ahmed Khan, he took the pen-name ‘Tanvir’ when he began writing poetry. He matriculated from Raipur in 1942, graduated from Morris College, Nagpur, in 1945, and went to Bombay to pursue an acting career in cinema. The War was winding down, the Quit India movement had already poured volatile youth on the streets, and Habib witnessed the heady days of the RIN Mutiny. He soon became a part of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was formed in Bombay in 1942.

In 1954, Tanvir moved to Delhi, where he worked in children’s theatre, and for Qudsia Zaidi’s Hindustani Theatre. In Delhi he met the young actress and director Moneeka Misra, whom he later married.

Habib and Moneeka Tanvir. Backstage during a performance of Charandas Chor, Jaipur, Rajasthan, October 2002. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande.

Habib and Moneeka Tanvir. Backstage during a performance of Charandas Chor, Jaipur, Rajasthan, October 2002. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande.

Tanvir’s first significant play, Agra Bazaar, dates from this time. It is a celebration of the life and work of the plebeian poet Nazir Akbarabadi, an older contemporary of Ghalib’s. Hardly any biographical information is available about Nazir, so Tanvir was forced to devise a play in which the protagonist never appears. The play is set in the bazaar, the locale that has kept Nazir’s poetry alive. With virtually no plot, the play was a stylistic novelty in its time. Tanvir drew the residents of Okhla village in Delhi into the play, an experiment that was to be repeated on a more sustained basis with Chhattisgarhi rural actors some years later.

Qudsia Zaidi died prematurely, and Habib Tanvir set off for England to train at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts (RADA), and the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. In England he learned many things, including British discipline, the principles of blocking, and some tricks of a director’s craft; but mostly he learned what he did not want to do. It seemed to him that English theatre was too rigid to allow the free movement that Indian theatre demanded. Western theatre, following Aristotle, demanded the unities of time, space and action; while Indian theatre, both the ancient Sanskrit and rural, broke these unities constantly, admitting only one unity, that of rasa.

Tanvir wandered in Europe for some time, watching plays, learning gypsy songs, and sometimes earning money for his passage by singing songs from his native Chhattisgarh in bars. He eventually arrived in Berlin, determined to meet Bertolt Brecht. The year was 1956; while Brecht had recently died, Brecht’s productions were still alive. Tanvir was struck by the simplicity and directness of the Berliner Ensemble productions. He was reminded of Sanskrit drama, with its ‘absolute simplicity of technique and presentation’.

The Prism of Chhattisgarh

Tanvir’s first significant Chhattisgarhi production, Gaon ka Naam Sasural, Mor Naam Damaad, was put up in 1972. His play Charandas Chor, created during 1973-74, won the Edinburgh Fringe First Prize a few years later, catapulting Tanvir and his band of rural actors to stardom. The play even had a London run, where it played to packed houses.

Several other successes followed, such as Mitti ki Gaadi, his Chhattisgarhi adaptation of Sudrak’s Sanskrit classic, which he presented in 1977, and soon after, Bahadur Kalarin, an oral rural Oedipal tale. By the mid-1970s, Tanvir had already evolved a distinctive idiom, and subsequent years saw him elaborating and refining it. By the time people came to watch Shajapur ki Shantibai (Brecht’s Good Person of Schetzuan) in 1978, and Lala Shohratrai (Molière’s Bourgeois Gentleman) in 1981, they tended to take his style for granted. It could quite easily be forgotten that it took Tanvir fourteen long years, from 1958 to 1972, to arrive at this style.

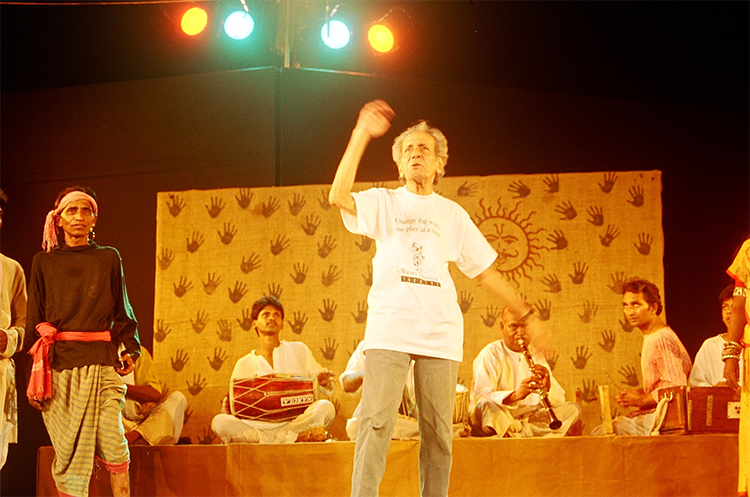

Habib Tanvir sings and dances during the Prithvi Festival, Mumbai, November 2003. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande

Habib Tanvir sings and dances during the Prithvi Festival, Mumbai, November 2003. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande

Two assumptions are often made about Tanvir’s theatre. One ascribes a development of IPTA’s legacy in his work, and the other views him as a practitioner of ‘folk’ theatre. Both are incorrect.

While IPTA used ‘folk’ forms essentially as carriers of revolutionary ideology to the masses, Tanvir fashioned a popular modern theatre, borrowing elements from rural dramatic traditions, a Utopian rather than revolutionary theatre.

Tanvir was not after folk forms, but folk actors.

In 1958, he got his first set of six rural actors, who brought their forms with them. He worked on several plays between 1958 and 1972, but most were, as he put it, ‘failures’. He wondered why these rural actors, excellent in their own setting, were stilted and trite in his own plays. He identified two main faults in his own approach: first, he was trying to impose his English methods on them; and second, he was forcing them to speak Hindi, which they were uncomfortable with, rather than Chhattisgarhi, in which they were fluent. Once he allowed them greater freedom of movement and use of their own language, the actors bloomed, and so did Tanvir’s theatre.

As a playwright and director, Tanvir had amazing range. Besides writing his own plays, he worked on plays by the old Sanskrit writers Sudrak, Bhasa, Visakhadutta and Bhavabhuti; he recreated European classics by Shakespeare, Molière and Goldoni; he worked with the writings of the modern masters Brecht, Garcia Lorca, Gogol, Gorky and Wilde; and with the works of Indian writers Rabindranath Tagore, Sisir Das, Asghar Wajahat, Shankar Shesh, Safdar Hashmi, and Rahul Verma. He adapted stories by Premchand, Stefan Zweig and Vijaydan Detha for the stage, and also adapted oral tales from Chhattisgarh.

Habib Tanvir, then, was a citizen of the world, borrowing, reading, soaking up influences indiscriminately. But he became, through a long, hard, creative struggle, a resident of Chhattisgarh. Chhattisgarh is the prism that refracted his creative expression. His autobiography was to be called Ek Matmaili Chadariya—a life woven with multiple threads, a life the dusty colour of earth. He was Midas turned upside-down: whatever he touched lost its sheen, became rough and turned Chhattisgarhi.

Celebration of the Plebeian

This is a man the Hindu Right hounded since the early 1990s. To argue that Habib Tanvir is anti-Hindu, and by extension, anti-Indian, is not a reflection on the man and his work, but on the depraved worldview of his attackers.

Tanvir remained close to radical causes. He directed a play for Jana Natya Manch in 1988, and was in the forefront of the protests that followed Safdar Hashmi’s murder at the hands of Congress goons in 1989. Over the years, both he and the Left moved closer to each other; and in the context of the attacks on him by the Sangh Parivar, and his refusal to bow to their dictates, he became something of a hero for leftist cultural activists.

If there is one theme that runs consistently through all of Tanvir’s creative output, from early works such as Agra Bazaar to the present, it is the celebration of the plebeian. The culture, beliefs, practices, rituals of Chhattisgarhi farmers and adivasis, their humour, their songs and their stories – it is these which gave his theatre its incredible vitality. His characters do not lack religiosity, but have a down-to-earth, straightforward relationship with god: Charandas prostates himself in front of god in all sincerity before purloining the idol. Tanvir was fascinated by the openness and eclecticism of rural adivasi religiosity. One of the reasons he opposed Hindutva is because it seeks to destroy this pluralism, and wants to regiment the belief systems and practices of farmers and adivasis.

Tanvir was an enemy of bigotry, parochialism, the kind of ‘development’ that crushes the poor, and of fundamentalism in any form. If Jamadarin/Ponga Pandit critiques the caste system, his adaptation of Asghar Wajahat’s Jis Lahore Nai Dekhya Voh Janmya hi Nai attacks Islamic fundamentalism.

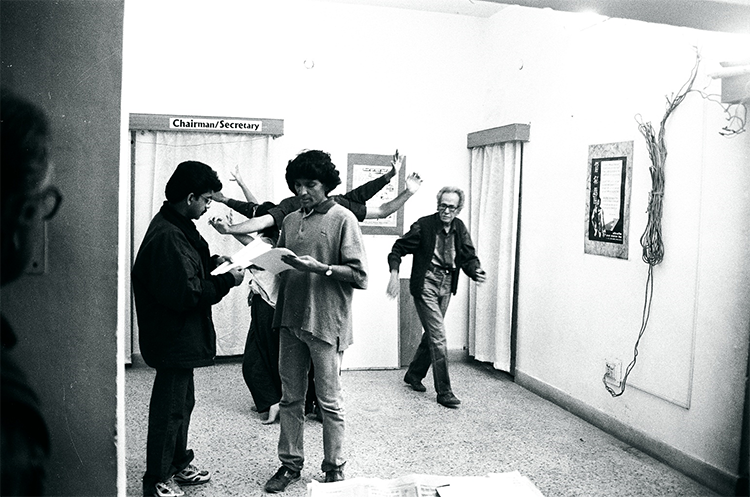

Habib Tanvir rehearsing Zaharili Hawa, Rahul Varma’s play on the Bhopal gas tragedy, Bhopal, December 2003. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande.

Habib Tanvir rehearsing Zaharili Hawa, Rahul Varma’s play on the Bhopal gas tragedy, Bhopal, December 2003. Photo by Sudhanva Deshpande.

The breadth of his work shows his engagement with issues of social justice. His last production, Raj Rakt, based on Tagore’s Visarjan, is also a critique of superstition. An earlier play, Moteram ka Satyagraha, based on a Premchand story and written in collaboration with Safdar Hashmi, is a humorous look at what happens when religion starts meddling with politics. In the aftermath of the demolition of the Babri Masjid in December 1992, he produced, for a Delhi group, Sisir Kumar Das’ Baagh, an allegory on the communal tiger on the prowl. In 1999, he wrote and directed, for Jana Natya Manch, Ek Aurat Hypatia Bhi Thee, a play on the fourth-century woman mathematician from Alexandria who was lynched on the streets by Christian bigots. Sadak, a short play, is a comic critique of the ‘development’ that ravages villagers, adivasis, their land and culture. Hirma ki Amar Kahani is a more profound look at what development has meant for adivasis. An early short children’s play, Gadhe, is a rip-roaring take-off on the education system that produces asses. His production of Rahul Verma’s Zahareeli Hawa is a fictional recreation of the Bhopal gas tragedy. Then there is Dekh Rahe Hain Nain, perhaps his most refined play philosophically, the story of a king’s futile quest for a calling that will harm no other being.

This, then, was Habib Tanvir, a man who represents two great traditions of Indian theatre – the tradition of the actor-director-playwright-manager, as well as the tradition of an active involvement, from the Left, in larger social and political causes. The first tradition became extinct with Tanvir’s death. The second tradition, happily, survives. Some of the credit for this must go to Habib Tanvir, for showing us the way.

All the photos in this essay are © Sudhanva Deshpande.

See excerpts from Sudhanva Deshpande’s film on Habib Tanvir,

My village is theatre, My name is Habib