The sea has been on the move in Karachi. Over the decades, as the city has burst its seams, it has moved farther and farther away into the distance. If you arrive very early in the morning at the beaches closest to the city and drive out until the road ends, you can sometimes see how this banishment of the sea is accomplished. Solitary lines of trucks, weighed down by their cargo of gravel and sand, empty their loads, making marsh into land. The land they make is sold at high prices, entire neighbourhoods of the wealthy stand on it, proud high houses encircled by high walls, looking defiantly at the sea they have pushed so far out into the distance. They are not afraid.

The poor are not afraid either, or perhaps fear is a luxury they cannot afford. As Karachi has grown from a few million to ten million and now to twenty million, droves of them descend on city beaches on the last day of every week, even more on Eid or on Independence Day. Two or three or four fall off the thin, worn seats of motorcycles, ten or eleven spill from small Suzuki trucks. Everyone is dressed in their best, the women in bright floral prints or black burkas yell at children who do not listen. Surrounded by husbands and fathers and uncles, guardians of their broods, they make their way out to the water. Groups of just men come too, some holding hands, their beards and their long trousers wet with salt spray. All of them jump in, let the waves splash their feet and their faces. The city is behind them, they know, and so too must be the filth that is born of it.

They are wrong. The houses and high-rises closest to the ocean are not connected to the city sewage system. The waste that accrues from them flows, untreated and unhindered, into the ocean. The elite clubs that have opened up to cater to the ocean-side-dwelling wealthy, dump all their waste into the ocean also, all the grease from wedding banquets that feed a thousand, all the pesticide-laden groundwater they use to water their acres of lawns in the desert of Karachi.

The Lyari and Malir Rivers, both of which empty into the same sea, bring their own gifts. Their banks further up into the city are lined with factories, leather tanneries, paper mills, medical and chemical manufacturing operations of all kinds, legal and illegal. Everything that they do not use, everything that is created in the process of making something else, is pushed into the ocean. This is the toxic brew in which the poor beach goers of Karachi, the young children, the expectant mothers, the old aunts and the scowling, solemn fathers, bathe when they immerse themselves into the ocean. They also leave their own gifts behind. At the end of every weekend, their Styrofoam cups, their bottles of soda, the plastic bags in which they brought their snacks, their lost shoes and all their discarded detritus covers the beach, joining the tons of toxicity at the edge of the city.

**

The poor of Karachi who so eagerly and ardently plunge themselves into an ocean that is fetid with the effluents and excrement of the city are what Naomi Klein would call the ‘sacrificial people’ of our planet. They include economic migrants, arriving from small villages dotted all over the country for jobs in the metropolis. Many of them are single men who have never seen the ocean, who spend their days inside airless factories, labouring at jobs that pay nearly nothing. When something is left of this nothing, they come to the sea.

Then there are those who have fled to the city to escape the war in Pakistan’s north, their villages pillaged first by the Taliban, then by American drones and ultimately by the “clean-up” operations carried out by the Pakistani military. They too come to Karachi, live on its outskirts, their families crammed together in the homes of relatives. Like millions of others, they search for jobs and if they find them, and perhaps even if they do not, they come to the sea.

The luckiest of both of these groups hope that they will progress on to other seas. Many among the economic and war weary migrants who come to Karachi hope to migrate to other seas. The lucky ones who do, graduate into the economy of fossil fuel extraction, to desolate oil rigs in the Persian Gulf. Their sacrificial bodies will toil and take from the earth the oil that lies at heart of the world’s conflicts. It is in the extraction of oil that they locate the fulfillment of their small dreams, the house to be built, the sons to be educated. The stories of these men are stories of survival, and in the midst of its urgent demands, it is easy, as Edward Said did, to discard the concerns of environmentalism as a ‘bourgeois conceit’. What is easy, however, is not always true.

**

Mai Kolachi was a fisherwoman who lived by the Indus Delta. Today her name adorns an overpass that connects the city’s busy port to the highways that snake through the remainder of Pakistan. It is a peculiar irony that the name of a woman who harkens back to the origins of Karachi as a sleepy fishing village is attached to a project that has involved the destruction of crucial portions of its ecosystem, but that is how it is. Unsurprisingly, the seeming urgency of constructing an overpass that required the dislocation of slum dwellers and the evisceration of mangrove forests was necessitated by war. In 2001, when NATO troops poured in next door to fight the war in Afghanistan, the port of Karachi became the node at which all the supplies for them were brought to shore. The transport of these crucial materials of war that would kill thousands across the border required an overpass that would permit the NATO supply tankers to bypass city traffic and gain fast access to the highway. In this way, multi-million dollar Mai Kolachi Overpass Project was born.

So it was that the ingredients required to kill in Afghanistan necessitated first the destruction of environmental ecosystem in Pakistan. The overpass was routed through the lush mangrove forest at Chinna Creek, destroying what was a natural rainwater drainage ditch. Locating the Overpass in the rain drain thus reduced the capacity of rainwater to flow directly into the ocean. This means that the oldest portions of the city, now also some of the poorest, are flooded by rainwater every single monsoon. The fetid water that has nowhere to go stands in the streets and in homes for days, becoming infested with mosquitos and flies. These in turn breed diseases, leaving hundreds sickened by cholera, malaria and dengue fever.

The mangrove forest that once was also disappeared from along the sides of the road that connects to the overpass. So too has its capacity to serve as a barrier for approaching hurricanes and cyclones. The migratory birds, cranes and pelicans that stopped in the forest every year coming south from Central Asia have no place to stop. Where there was once something living and beautiful, there is now a road whose primary goal is to transport the building blocks of warfare.

Perusing through old newspapers from the time of the construction of the Mai Kolachi Overpass, I found a quote by one of its most vociferous opponents, Parween Rehman, an urban planner and environmental activist who headed up the Orangi Pilot Project (located in one of Karachi’s largest slums). ‘All land reclamation needs to be stopped immediately’, Rehman had held unequivocally. ‘The backwaters should be returned to their natural state and a flyover constructed where Mai Kolachi passes over the natural drains. At least one flyover should be made for the fish and mangroves. Why just for the cars? Fish also need to cross to the other side. We’ve killed them and finished them off’.

None of that ever happened, of course, but more tragedy did. Just like the fish and trees that had been a casualty of the $700 million dollar Mai Kolachi overpass, Parween Rehman was herself killed, a little over a decade after she had given that interview and as she had continued her opposition to projects that destroyed environmental ecosystems, scapegoated the poorest of Karachi’s citizens and exposed land grabs by the city’s powerful. Parween Rehman was gunned down by assailants on 13 March 2013. Over three years later, the case was still dragging on, with no one yet punished for the killing.

The Mai Kolachi Overpass must have transported hundred of thousands of tons of military equipment in the decade and a half since the NATO invasion of Afghanistan. It is now a fixture of Karachi’s urban transportation system, a whole generation grown without knowledge of a time when it did not exist. In 2011, the outline of a sharp new building emerged against the skyline of the overpass. The new US Consulate of Karachi, the newspapers boasted, was built according to the ‘latest technology’. At its inauguration, then US Consul General William Martin said that the new building ‘clearly reflects the enduring relationship between America and Pakistan and is a commitment by the American people and the government to stand with Pakistan in the long term’. Speaking specifically to the location of the new building, Consul Martin added, ‘This is a historic and important move. I am looking forward to showing the people of Sindh and Balochistan our new consulate complex. Our relocation enables us to continue building a strong and mutually beneficial relationship between the American people and Pakistanis’.

**

There is much that is written and much that is said about the War on Terror, Pakistan’s role in it. It is rare, however, that the story of terror is linked to the violence done to ecosystems, to slum-dwellers and to the poor and desperate and those who advocate for them. Naomi Klein refers to just this when she writes, ‘there is no way to confront the climate crisis as a technocratic problem, in isolation. It must be seen in the context of austerity and privatization, colonialism and militarism’. The story of the Mai Kolachi Overpass reveals the interconnections between Karachi’s endless drive for land reclamation, the exogenous forces that demand destructive shortcuts, and the ravaged ecosystems that are left behind in their wake.

Stories like that of the Mai Kolachi Overpass are scattered through the injured terrain of our warming world. If the south of Pakistan, its ports and coastal belts had to be made available for transport supply lines, its north was patrolled by drones. Many of the areas that were patrolled by these remote controlled bombers have also had the basis of their livelihoods drastically altered by resource extraction. Communities in North Waziristan, a part of the fetishized and bombed out ‘tribal lands’, once depended on subsistence agriculture. Then mining came along, with gypsum mines and men began to work there, abandoning agriculture and developing a new exploitative relationship with the land that birthed them. When mining operations shut down or required less labor, there were no jobs. Men left, for Karachi or for the Gulf. Fatherless sons were left to the machinations of the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, who offered a possibility of crude and cruel revenge against larger forces and a raped and pillaged landscape.

The task of the climate activist of the future is the task of telling these stories, of, as Klein puts it, ‘overcoming these disconnections, strengthening the threads, tying together our various issues and movements’. It is only in telling these stories, replete as they are with both the tragedy of loss typified by the construction of an overpass in Karachi, that there can be hope for a truly inclusive and truly radical movement against climate change. It is only when this corrective is taken seriously, when the case for interconnection and urgency can be made via the story of a road named after an old lady but which killed much that was old, much that was treasured and much that was living, that a kinder, future can be hoped for.

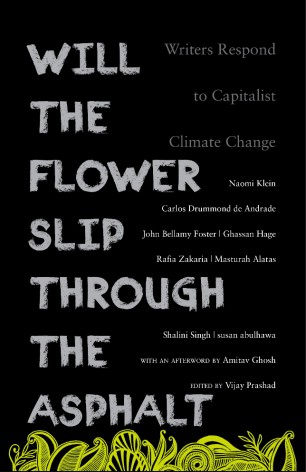

This essay is part of a collection of essays on capitalist climate change brought out by LeftWord Books: Will the Flower Slip Through the Asphalt: Writers Respond to Capitalist Climate Change.