August 29, 1970: The Maharashtra Theatrical Performances Examination Board (MTPEB) banned Vijay Tendulkar’s play Gidhade (The Vultures), contending that its realistic portrayal of perverted socio-familial complications was unsuitable for a public performance. An extended battle led by the producer, Satyadev Dubey, and the director, Shriram Lagoo, resulted in the play being certified for release after a few token cuts. With a stroke of satirical genius, the play, on its release, began with the following deadpan announcement: “In compliance with the objection from the Censor Board, the red stain on the rear of her sari of a particular female character who leaves the stage back to the audience, will henceforth be blue in colour.” The show began to uproarious laughter and thundering applause, a landmark moment in the evolution of Marathi theatre.

August 19, 1974: The Maharashtra Government decided to ban a production of Mahesh Elkunchwar’s Vasanakand (The Inferno of Lust) that I directed. I appealed to the Honourable High Court of Bombay for revocation of the ban. The MTPEB contended that “The incestuous relationship between a brother and sister shown in the play is immoral, hence likely to offend audiences and may result in vandalism, triggering a law & order situation.” The Honourable Court ruled unequivocally for the plaintiff, maintaining that “If such situations arise, the Government is administratively responsible for curbing the disorderly elements while protecting the artistes to complete their performance without any hindrance.” It was 5 p.m. when I got the order. Tearing my way through rush hour traffic from the High Court to Ravindra Natyamandir, Prabhadevi, I was up on the stage at 7 pm.

August 30, 1996: The Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) objected to a scene from my film Daayraa (The Square Circle), and asked for some allegedly obscene dialogue and phrases to be deleted. The narrative was of a romance between a man who turns into a transvestite after years of portraying female characters in folk plays, and a woman forced to dress in male attire to ward off sexual predators. The assiduous members of the Board objected to a scene in which a “madam”, running a sex racket with her two henchmen, abducts a young girl. Having sought an “A” certificate in the first place, I fought endlessly. Finally, with no deletion in any scene and minor changes in some dialogue, Daayraa went on to win the National Award and a Grand Prix in France.

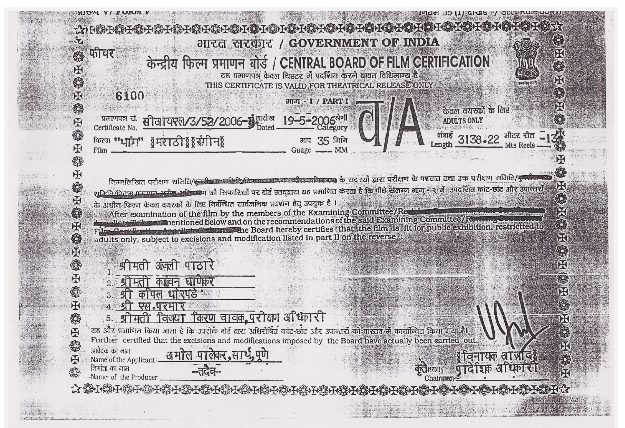

2006: My film, Thang/Quest, a bilingual film in Marathi and English, dealt with the repressed homosexuality of its male protagonist who has a heterosexual marriage. A film that demanded deep introspection from the audience, it received, as expected, an “A” certificate for the English version. In a moment of perplexing and disheartening inconsistency, the same CBFC (with different Board members though), decided to ban the Marathi version. This was certainly unacceptable to us. In the discussions that followed with the morality brigade on the CBFC, I drew attention to Brokeback Mountain, a prominent American film dealing with homosexuality, which had been certified for its release just a few months earlier. I asked if their implication was that the Marathi audience was less mature and tolerant than the English speaking audience. Their retort was, “These things may be okay in foreign films but they don’t fit into our Maharashtrian Culture.” Even after I pointed out that great Marathi litterateurs such as S. N. Pendse, C. T. Khanolkar and Vidyadhar Pundalik had dealt with homosexuality in their fictional works, their Nay was loud and clear. They backed off only when Sandhya Gokhale, my wife and writer and co-director of the film, demanded as a lawyer that they, “must record their objections in writing so that a war may be waged in the court”. Without anything in writing, both versions of the film were released with “A” certificates.

2010: When I read the script of Vivek Bele’s play, Maruti and Champagne, I was excited by the prospect of a superb play in the offing. Anticipation soon curdled into despair when I learnt that the mention of Maruti “offended the sentiments of a certain community” and was drawing shrill vituperation. I reached out to Mohan Agashe as a head of the production house of the play, and offered him a hand to fight such extra-legal censorship. His prostration before the mob became evident when he said that the production was to be renamed “Monkey holding the Champagne”. I was disheartened, since such retractions boost the mobocracy. Moreover, he was an actor in Vijay Tendulkar’s Ghashiram Kotwal which was similarly threatened, but which case had been successfully fought in the court.

January 2012: Symbiosis University, Pune, announced a private show of Sanjay Kak’s short film on Kashmir, Jashn-e-azadi. Activists of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) demanded that the screening be cancelled as it was likely to hurt local sentiments. Obvious questions such as “Has anyone who raises such objections actually seen the film?” or “Can you identify specific objectionable material?” were given short shrift. Before spinelessly cancelling the show, the Director should have spent a moment over the message his action sent to his students.

June 14, 2016: The CBFC raised an astonishing 89 objections to Udta Punjab but refused to spell them out in writing. The source of panic was that the film might damage the reputation of the Punjab Government. In times past, Nargis Dutt, then addressing the Rajya Sabha as a nominated member, expressed anguish at the unflattering portrayals of Indian poverty seen through the lens of the legendary Satyajit Ray and his new-wave cinema contemporaries. She saw it as an affront to our national pride. How did the legend who immortalised the title Mother India descend to such inanity? Around the same time, the Culture Czar of the day, Minister Vasant Sathe, placed a ban on my film Akrit from participation in international film festivals. Senior artists, including Shombhu Mitra, P. L. Deshpande, and Durga Bhagwat, addressed a joint letter to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, castigating this unreasonable fatwa. It was soon lifted. Just for the record, Sathe had ordered a similar fatwa against foreign performances of Ghashiram Kotwal in 1980. Again, Indira Gandhi vetoed his decision.

Amol Palekar / Image courtesy the author

Amol Palekar / Image courtesy the author

Artistes have long been at the receiving end, often violently so, of the intolerant mob. Balbir Krishan, whose art echoes his homosexuality, faced a violent attack in Delhi; M. F. Hussain had to be in exile in his twilight years after facing death threats; Taslima Nasreen is still unable to find sanctuary in India; Salman Rushdie’s permission to speak at a literary festival in Jaipur was withdrawn at the penultimate moment; the Mumbai University withdrew Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey from its curriculum; a statue of Dadoji Konddev was spirited away overnight from its prominent location in Pune’s Lal Mahal; Joseph Lelyveld’s book Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India was banned in quick succession by the Gujarat and central governments. We have a long, ignominious history of abject prostration before intemperate, anti-intellectual mobs. I, for one, feel extremely agitated to see that despite these examples spread over five decades, nothing much has changed.

In Chapter 22 of his epic treatise on Politics, Niccolò Machiavelli identifies three types of intelligence. “One kind understands things for itself, the second appreciates what others can understand, [and] the third understands neither for itself nor through others.” He goes on to say, “This first kind is excellent, the second good, and the third kind useless.” It is sobering that it is the ubiquitous abundance of the last type that characterises our society. Katherine Mayo was an American historian whose polemical work, Mother India drew opprobrium even from Mahatma Gandhi. In a stinging rebuke, he commented, “It is the report of a drain inspector sent out with the one purpose of opening and examining the drains of the country to be reported upon, or to give a graphic description of the stench exuded by the opened drains.” Yet the Mahatma’s open-mindedness became evident when in later years, he urged all Indians to read the book, if only to understand the calumny that the colonial masters poured on their subjects in a disingenuous defence of their occupation. It is to our country’s eternal shame that the Mahatma’s exhortation has been forgotten and, seven decades after Independence, the book continues to be banned in India.

I have been, and will remain, an untiring advocate against the mentality and mechanisms of censorship. Bans and censorships are abhorrent manifestations of denial of plurality of thought, and voices of dissent. Anger at, and intolerance to dissent, makes fodder for an insidious form of anti-intellectual tyranny. It imposes the bigotry and narrow-mindedness of a bullying minority upon the largely apathetic majority. Whether this pressure is exerted through mechanisms of the state or otherwise, curbing and controlling artistic expression ultimately has a chilling impact on all expression, even the most anodyne sample.

Efforts at curbing expression share some characteristics:

. Censorship is cited as a tool to protect the nation’s sovereignty and integrity. At the pinnacle of its imperial arrogance, the British Empire in India found no cause to curb overt challenges to its sovereignty. This is true for all manner of creative works of the times. There were no attempts to ban the Marathi play, Kichak Vadh, an allegory on the colonial despoilment of India, or a song like Door hatoa e duniyavalon, ye Hindostan hamara hai on the grounds of sedition.

. “Incitement to hostility between groups” or “likelihood of grievously offending sentiments of a particular group/ community/ religion” is another weapon. One needs to look no further than the unambiguous decision of the Bombay High Court in the matter of Vasanakand for a searing rebuttal of this argument.

. A perverse thesis is being introduced in social discourse on the arts. It runs along these disingenuous lines: “The creative arts exist only to amuse and entertain. They have no business poking their noses in revealing a society’s iniquities and injustices, its warts and blemishes.” The history of all creative expression readily reveals the hollowness and falsehood of this contention. Across the aeons, the artist has recorded, ridiculed and satirised her contemporary context.

The Udta Punjab controversy has abruptly brought this discourse out of the arcane realm of academic debate into the court of public opinion. It is not inconceivable that the current CBFC might be reconstituted. However, a fundamental reworking of the entire censorship structure needs legislative action. The Cinematograph Act, 1952 will need to be abrogated and fresh legislation drafted, and adopted by the Parliament to replace it, keeping the changed circumstances of the 21st century in mind. It is anybody’s guess how easily such a radical overhaul of the structure sits with an establishment that wishes to impose its will on what we will eat or drink, or what we may say or see!

There is a more fundamental issue that underlies the censorship structure. The constitutional validity of the Cinematograph Act needs to be challenged. Till this challenge is rigorously mounted, a few fatuous guardians of our minds and morals will continue to be entrusted with a crude pair of scissors to perform their harebrained duty. It is a matter of de facto reality that the Act is patently discriminatory, and falls foul of the overarching equality before the law guaranteed by the Article 14 of the Constitution. What might the legal line of argument look like?

IF

. Literature, theatre (as an exception in Maharashtra), dance and other forms of creative expression are not subject to censorship;

. Speech, both written and oral, or articles, no matter how offensive, require no pre-screening nor attracts any censorship;

. Television programming of any sort, news, current affairs, entertainment or whatever else, is free of censorship (except to the extent that it carries cinematic content);

THEN

What is the precise legal justification for encumbering the cinematic arts exclusively to the burden of censorship? Discriminating among the various forms of creative expression in this manner is irrational, unfair and untenable against the touchstone of the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law. What is the rationale behind, and what is the object of such differentiation?

In our current situation, there are just two alternatives to put this discriminatory regime behind us. Either we dismantle the odious structures of cinematic censorship. Or we bring all creative forms of expression under censorship. Evidently, the latter option must be abhorrent in the extreme to any believer in India’s democratic, progressive polity. An intelligent, culturally aware, literate, aesthetically evolved citizenry must take an uncompromising stance against illiberal forces of bigotry and thought control. All of us need to unite for such causes; else this will remain a solitary individual fight, making no dent.

Sandhya Gokhale sums it up well:

No nation-state accepts unbridled and unbounded freedom of opinion or expression. One person’s freedom exists only with a deep commitment to the same freedom for his fellow citizens. In other words, one person’s freedom does not come bundled with the right to trample upon those of his fellows. All freedoms are circumscribed within specific social and cultural context. As soon as we begin to accept this line of reasoning, we experience a sense of unease that something crucial and essential to freedom is slipping away. This is where we enter the amorphous terrain of individual or group specific constraints. In the scarcity or absence of ethics, values, respect, mutuality, it is easy to get mired in the quicksand of subjectivity. Perhaps it was precisely this sort of a world that Rushdie transported us to in his Haroun and the Sea of Stories. The Land of Chup is a land of oppressive silence where the Sun would never rise. Right next door, the raucous, argumentative land of Gup, always enjoyed bright sunlight. It is for us to decide whether we want to be citizens of Chup or Gup. Freedom and Rights are human artefacts. Do they deserve protection? Should we strive to protect those and to what extent and at what cost? We need to grapple with these and attempt to answer. Impotent finger-pointing at mobocratic armies of the intolerant and easily offended will only end in the pounding out of all freedoms and we would have brought this bleak consequence upon ourselves by our apathy. We will have to satisfy ourselves with little morsels of tightly circumscribed freedoms that the establishment tosses at us from time to time.

‘Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’ Who can forget this unmemorable line from George Orwell’s 1984? If we want to have a sun rise every day as was shone over the land of Gup, the time to decide is high, and that is a certainty.

Also see:

A clip from Vijay Tendulkar’s Gidhade (1961):

Amol Palekar on Thang/Quest:

Sanjay Kak’s Jashn-e-Azadi: