India prides itself in a rich tradition of diversity, dialogue and debate. Our democracy draws its sustenance from this tradition. Myths, texts and systems of faith and thought have been cherished, revisited and also challenged. They have often inspired imaginative versions through oral retellings and local adaptations. The dynamism of Indian culture has kept it open to influences and has stood the test of time. In Words Matter, edited by eminent poet and scholar K. Satchidanandan, scholars and writers including Romila Thapar, Githa Hariharan, Pankaj Mishra, Salil Tripathi and Ananya Vajpeyi discuss these definitive values from various points of view.

In their perceptive and insightful essays, the contributors argue that we must nurture critical thinking to fight all kinds of discrimination and insularity. It lies in our interest as a modern nation to preserve our cultural strength and help democracy flourish. The book includes excerpts of the writings of Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare and M.M. Kalburgi as well as articles and speeches by eminent people like Markandey Katju, Shyam Saran, Nayantara Sahgal, and Keki Daruwalla.

An extract from Gopal Guru’s “For Dalit History Is Not Past but Present”

It is possible to argue that the act of privileging a particular social tragedy, such as the displacement of Pandits, as the only context for defining intolerance has the following limitations. First, the counter protest against the writers seeks to privilege the displacement of Pandits as a kind of spectacular tragedy and hence such position by implication tends to ignore other tragedies. It may be because such tragedies are regular rather than spectacular. And, when this does not even occur to the opponents, Dalit tragedies have to wait for the social attention of these historically sensitive supporters of the Pandits. In such a reading, social history tends to move ahead primarily through the suffering of the privileged sections of society. Second, a particular reading of tragedy does not tell us whether the tragic experience of displacement has led the Pandits to identify with those who have been facing different kinds of displacement. For example, the supporters of Pandits do not tell us whether the experience of ghettoization has morally inspired the Pandits to make common cause with Dalits as another displaced and despised social group. Instead, they seem to be using the dislocation of Kashmiri Pandits as a moral stick with which to beat the protesting writers.

Ironically, displacement of Dalits is not merely a physical or territorial dislocation, neither is it a loss of social and economic domination; it is, in fact, a colossal moral loss of their human existence. The ideology of purity–pollution which is the core of Brahmanism, forces Dalits to carry with them all the time a morally degrading meaning, even if some of them have moved out of defiling jobs such as scavenging and other sanitary works. Those Dalits who still find themselves chained to the obnoxious job of manual scavenging and rag picking continue to remain repulsive objects of intolerance. The touchable caste pushes Dalits first into degraded/inhuman forms of jobs then uses the same dislocation and stigmatizes them. Thus the upper castes invent justification for their intolerance of Dalits.

This burden of stigma remains attached to Dalits across time and space. The ideology of Brahmanism thus turns Dalits into a walking carcass or mobile dirt, and their colonies into stigmatized ghettos that look almost similar to the apartheid that existed in South Africa. Yet, in the privileged imagination of the film stars who are opposing the writers, social existence that has been reduced to repulsive wretchedness does not have the moral calibre that could help foreground intolerance.

The intolerant attitude adopted by the upper castes towards Dalits is morally vacuous in two major senses. First, those whose attitude of intolerance renders the Dalit untouchable or even unseeable, just because the latter deal with human dirt, conveniently forget that they themselves are the source of such dirt. Upper-caste intolerance, thus, inflicts civilizational violence against Dalits. Secondly, those who push Dalits out of the civilizational sphere do not take the responsibility of seeking the exclusion of Dalits from human interaction… Devastating expressions of intolerance, which for Dalits produce an everyday experience of humiliation and hence social death, however, do not merit the critical attention of those who see conspiracy behind the protest by writers.

Sound as the Source of Intolerance

Sound as the source of intolerance has a known history of some eighty years. The corporeal sound embodied in the Dalit body made the upper caste of the temple town of Pandharpuram in Maharashtra intolerant to the extent that the latter thrashed the Dalits mercilessly. This was reported in the fortnightly Bahishkrut Bharat published by Babasaheb Ambedkar. Eighty years later a Dalit youth was killed by upper-caste youth in another temple town, Shirdi, in Maharashtra, the reason being the same—‘shrill sound’. In the case of Shirdi, what absolutely annoyed the youth was not the corporeal vocal sound but the ringtone playing Ambedkar’s song. This ringtone of the Dalit boy’s cellphone seemed to have irritated the OBC youth so much that they killed him instantly. What irritates the upper-caste Sikhs in Punjab is the song ‘Chamar Da Munda’ (the son of a Chamar), a legitimate cultural assertion of the Dalit youth of Punjab. One does not know how long the killers of Dalits would take to understand that music and art reintegrates human beings into everyday life. For a Dalit the ringtone of Ambedkar’s song works as the aesthetics of ordinary existence. It suggests how to govern one’s life in order to give it possibly the most beautiful form in the eyes of oneself, others and the future generation. However, the net consequences of the upper castes’ active intolerance force Dalits to adopt coping mechanisms. Hence, they are forced to edit out the acclamatory language that has Ambedkar in it.

Destructive Intolerance Leading to Self-Censorship or the Tonsuring of Language

Ambedkar has been an immutable expression of the cultural and social identity of Dalits. But in an event of increasing upper-caste intolerance, they are forced to culturally access Ambedkar only in an abbreviated form. They are, thus, forced to hide behind abbreviation because the so-called public sphere has been socially quite hostile to them. Hence Dalits have changed their usual ways of greeting each other with ‘Jai Bhim’ (Hail Bhimrao Ambedkar). They now say JB as a short form for Jai Bhim. This has an atrocious impact on the very words, in the sense that they are made to undergo a kind of photosynthesis. In such a natural process of photosynthesis, the words begin to shrink; they are condensed to their essence. As a consequence, Dalit life itself becomes synonymous with playing a reductive language game, and caste or social reality becomes synonymous with linguistic reality.

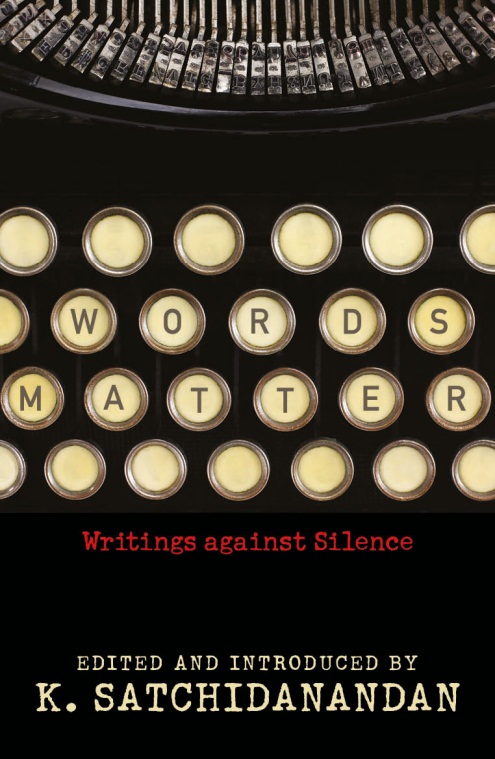

Excerpted from Words Matter: Writing against Silence, edited by K. Satchidanandan, Penguin Random House, 2016, Rs. 399.