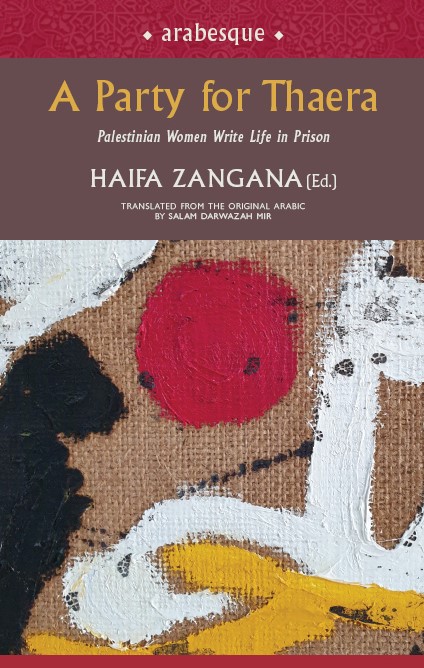

Edited by Iraqi writer and activist Haifa Zangana and published by Women Unlimited, A Party for Thaera: Palestinian Women Write Life In Prison brings together writings by Palestinian women who were former political prisoners. The book has been translated from the original Arabic by Salam Darwazah Mir.

In a first, nine politically-diverse women, former Palestinian political prisoners, sat around a table in a small room in Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank, to share their stories of incarceration. These non-writers learnt to express the reality of their time in prison, of the separation from their children, of the endless struggles against Israeli occupation, to produce heartfelt narratives that go beyond simply recalling the details of their sentence or revisiting their trauma. Instead, this unique volume transforms their experiences into an expression of the self, giving readers an “exceptional” insight into an almost unknown women’s world, of life and love behind bars and beyond.

The following excerpt is a chapter from the book written by Khitam Khattab.

The Bundle

At noon on March 28, 1982, the policewoman opened the car door and ordered me to step out quickly. I looked around. Before me, higher than my eye-level, I saw the words: Neve Tirtza. I realised we had arrived at the Ramleh Women’s Prison. I had already spent a month at Al Muskubīya Detention Center[1].

On the way, I tried to enjoy the beautiful landscape, the green hills and the tall trees of our villages, while softly humming the song, “My Land, My Land”. When we crossed our village, Kalonia, one of the many on the outskirts of Jerusalem, from where my family had been ousted in 1948, I cried bitterly. I remembered how Father, who had gone to check on the village after the 1967 war, came home with red eyes, having cried the entire way back.

The policewoman handed me over to the female prison guard. Her name was Hannah Hair, and she had short, kinky hair, was of medium height, and looked menacing. A little later, I was once again handed over to the store guard, who stared at me with her bulging eyes, then called me angrily, “Come here, mekhahbel”, which means terrorist.

I brushed her hand off my shoulder, as she dragged me to the warehouse to give me prison clothes. I was told to completely strip, including my underwear. Then she searched me as I stood there naked, even forcing me to bend down so that she could check my anus. I thought to myself: what’s wrong with her? Is she mad? I am stark naked. What could I possibly be hiding in my body? A bomb? Or…? I don’t know. Was it fear? Or was it the desire to humiliate and denigrate me?

It was my turn to receive a green dress, blue shirt and pant, and black shoes. When I told her, “I need a smaller size, these are too big.” “Shakat,” she replied, meaning be quiet, “these clothes are better than yours.” She also gave me a boqja (bundle) with two blankets, an old ragged pillow, and a spoon.

At first, I was delighted to receive the boqja. I thought: perhaps there is a surprise in here? Like in the boqja my mother would bring from the UNRWA[2], at the start of every season, when we were children. We would happily hover around her, patiently waiting to see what was inside. We would grab a few clothes and rush to try them on. Then the distribution began, each one got something according to their size. In the midst of all the fuss, my mother’s crying and muttering would stop us in our tracks. She’d say, “This boqja is the price of the land we used to plough; the price of the plums and grapes; the price of the Damascene cow that yielded a bucket of milk; the price of spring water that quenched our thirst and watered our land.” I also remembered my grandmother’s boqja, which she had carried on her head, with one end of her thobe[3] tucked into her belt. She was fleeing from the bombing that followed the martyrdom of the leader, Abdul Kader al Hussayni during al Qastal Battle (in 1948). Both my father and grandfather had fought in al Qastal.

Apart from her boqja, my grandmother had dragged along her daughter-in-law (my mother) and her three children: an infant son in one arm, with my two sisters holding on to her thobe. They were running away to seek refuge in my grandfather’s house in a village far away from the fighting.

As I carried my own boqja that day and walked through the long passageway in the prison, sighing in pain and anger, I thought: is this going to be our fate—to carry a boqja at every stage of our life? Is the boqja a part of us and our exile? I hate my grandmother’s boqja. I hate my mother’s boqja. And I hate my boqja, as much as I now hate the boqja of every Syrian or Iraqi refugee. I know what the boqja means—it means humiliation and indignity.