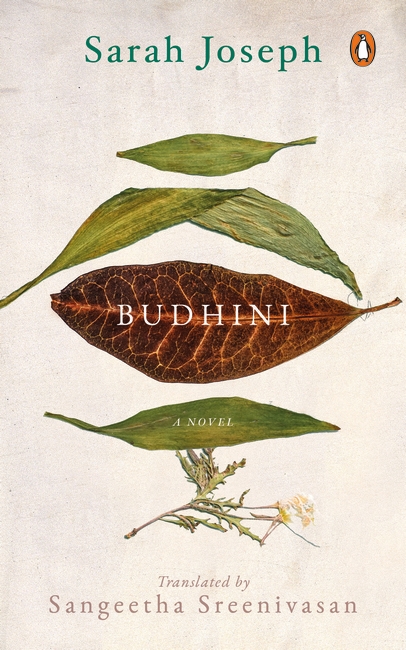

On 6 December 1959, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru went to Dhanbad district in Jharkhand to inaugurate the Panchet Dam across the Damodar river. A fifteen-year-old girl, Budhini, chosen by the Damodar Valley Corporation welcomed him with a garland and placed a tikka on his forehead. When these ceremonial gestures were interpreted as an act of matrimony, the fifteen-year-old was ostracized by her village and let go from her job as a construction worker, citing violation of Santal traditions. Budhini was outlawed for ‘marrying outside her community’.

Budhini Mejhan’s is the tale of an uprooted life, told here through the contemporary lens of Rupi Murmu, a young journalist distantly related to her and determined to excavate her story. In this reimagined history, Sarah Joseph evokes Budhini with vigour, authority and panache, conjuring up a robust and endearing feminine character and reminding us of the lives and stories that should never be forgotten.

Translated by her daughter, Sangeetha Sreenivasan, Sarah Joseph’s Budhini powerfully invokes the wider bio-politics of our relentless modernization and the dangers of being indifferent to ecological realities.

The following is an excerpt from the book.

Her hands were flushed with blisters on the first day that she went to work at the DVC. By twilight, large bubbles appeared on her palms, leaving her with a burning sensation. The liquid inside them tingled and itched until the following morning. Eventually, the abscesses ruptured and discharged a pus-like fluid and blood, blackening the handle grip of the hammer. The stone dust accumulated between her palm and the handle of the hammer penetrated her flesh, causing unbearable pain. The wounds finally healed but left behind calluses. Budhini resented breaking stones.

From morning to evening, it was just stones, her hands and a hammer. The stones sometimes emitted fire and sometimes blood, but never a god or a piece of poetry or a figurine. Sitting in rows with their heads down, many people, like Budhini, particularly children, pounded away at the rocks, reducing them into gravel-sized chunks. The contractors taking rounds would not permit them to raise their heads. Even when they did lift their faces, there was nothing to look at but the masses of pounded stones stretching towards the sky. All this while, grit collected in the pores of their faces, in their hair, in their clothes and even on their eyelashes.

The wind was grey, as was the sky, earth, trees, flowers and grass: grey birds, grey butterflies—a world of volcanic ash!

Deafening roars that perpetually girded the surroundings were unusual for Budhini. Karbona, her village, had been a lake of silence! At times a stone or fruit, or a flower, may fall into it, but mostly the undertones of bouncing fish or hopping frogs dominated the air. The bleating of goats, the short grunts of buffaloes, the barking of dogs, the squeal of pigs and the crowing of roosters contributed to the louder sounds.

The vibrations familiar to Budhini’s ears were the snapping of firewood on the stove in the courtyard, the rumbling of the millstones, the clanging of lotta, batti, kanda and other dishes, the plop-plop of dough being kneaded, the waa-waa of Aunt Phulmone’s baby. With the day coming to an end, these noises dissolved in the darkness. The darkness was for the Bongas. The hour of the dead souls! Silence!

However, the night, too, possessed delightful resonances. Out of the blue someone would play on his pipe, accompanied by the beats of distant tamaks. The banam player would find no rest either. With her heart on fire, feet growing wings, Budhini would come to the street. From the sinews of the banam a pleasingly painful melody would be flowing through the streets. By then, the dancers would have started taking steps. Deep down, they would be singing a song whose lyrics dribbled honey.

Ten drums,

Twenty young girls,

Endless, the dancing ground!

Hey drummer, don’t stir me up.

And if you do, I will make you swig,

A river in a mouthful.

Reflecting on the ambiguity of the song, Budhini smiled and then felt regret the next second. Even the voice of the person sitting next to her was not audible as they pounded the stones. The boom-boom of the rocks didn’t leave the ears even after one was home. Low voices stopped reaching the ears.

[…]

‘Baba, let’s go to the woods.’ ‘But, girl, where are the woods?’

The gormen took the woods and farms and walled up the river. They said they would give dams instead. Dams benefit not just one or ten villages but hundreds and thousands of communities.

What was the catch? All the villagers had farms near the river. Besides, they engaged in communal farming. There was fish in the river. There were stalks, roots and fruits in the forest. Now, there was nothing. The dam was rising. By the shores, the singers sang of losses:

Me,

A singer, angler, grower,

Oarsman, huntsman, drummer,

Oh, Sephali Haram Budhi,

They took away my song,

My fishing line, my little canoe,

Dhak and dhamak, arrow and bow.

‘Go to Manjithan’

Grandam Sephali told me,

‘Pick up the bow of Haram Bonga.’

Me,

In Manjithan.

Bowed to Haram Bonga,

Took his bow and arrow.

Ba,

In the woods of sal trees, they checked me.

I checked them from the massacre of trees.

There was no time for bow and arrow.

Ma,

They had guns with them.

Their fingers were white as white.

That was a tough time. They had seen nothing like this before. What would they do now? The people of Karbona were clueless.

Raghunath Haram, the oldest man in the village—a hundred and ten years old—pointed out: ‘Take a close look, the forest walks away.’

All of them saw it. Each day, by daybreak, the woods seemed to have marched some miles away. Earlier, the forest was straight across the fields. Later, a view became possible only from the lower dale. And then the forest was seen climbing up the hill. It seemed like the woods had settled on the summit for a while.

And then the forest started climbing down. The blue curtain that had been draped over the village was folded and set aside, leaving Karbona naked.

Each tree and offshoot was the home of the Bongas. Karbona was a double world that bore both the dead and the living. Both the worlds were equal. Both demanded shade and shadow. But presently, in the unbearable light, in the open expanse, the Bongas were getting restless. They were angry. Soon, their wrath would seal Karbona’s doom.

The villagers planted new saplings for the Bongas to rest. They pleaded to the Bongas to dwell inside the tiny plants and remain composed. They continued doing this till the gormen appeared to expel them.

‘This land belongs to the sarkar. Planting trees here is transgression,’ they said.

If you tell the gormen that the world of Bongas needs coolness and shade, and that they dwell inside the water, on the trees and in the folds of the ridges, they will not understand. All they know is that the land belongs to the sarkar.

Hundred-and-two-year-old Dhurgi Haram Budhi, the wife of Raghunath Haram, complained: ‘The mountains of Marang Buru are burning.’

Shielding her eyes with her wizened hand, she intently looked up at the sky. ‘My head breaks apart in the heat. Such scorching heat is new to Karbona.’

Her daughter-in-law, Hira, agreed saying, ‘By all means, Ma, when you brought me to this village, it was closed off on all sides by a lush jungle. The sun reached as a guest once in a blue moon. Sometimes, the trees touched the skies.’

Feeding his child gruel, Hira’s son came to the courtyard. ‘Trees are now floating down the river, Dadiya. They are on

their way to board a ship headed overseas,’ he said. ‘What’s that for, Sidho?’ his mother asked.

‘What’s there to know, Ma? The white folk will make grand wooden cots. And their houses, bigger than forests, will smell of sandalwood.’

After the woods, it was the fields. The government officials summoned the villagers.

‘Don’t you know the fields belong to the sarkar? Water needs to occupy space once the dam rises. So this time you are not supposed to farm here,’ they said. That was a strict order and the beginning of all their distress. Budhini was then a child of four or five. What had caused the entire village to suffer like this?