New Delhi: “Ever since Babu died I can feel fear stuck in my throat, rising to choke me,” said Pooja Kumar, who lives with her husband Ramesh in an area called Shahbad Dairy in north-west Delhi. Their son Sevak Ram died at the end of June, just days before his second birthday.

Ramesh was a shop assistant, but after the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded, business dried up, and food has been hard to come by. It is a story repeated across hundreds of similar slum neighbourhoods in a city that is among India’s richest by per captia income.

“I have lost my son, I want to hold on to my daughter,” Pooja told me, holding the pallu of her purple printed sari in one hand while clutching Rhea, her four-year old daughter with the other.

Despite economic growth and steady improvement in hunger and malnutrition indices over the years, India struggled even before the pandemic. In the 2019 Global Hunger Index, India ranked 102 of 117 qualifying countries, ranking below Pakistan and Nepal in south Asia and suffering from a level of hunger cateogorised as “serious”.

At the best of times, politicians in India rubbish claims of malnutrition. In 2012, when Narendra Modi was chief minister of Gujarat, he attributed his state’s high malnutrition rates to “beauty conscious” young women.

In a country where governments work harder to deny deaths by starvation than they do to prevent them, it would be impossible to establish Sevak Ram died due to acute malnourishment. He did have an underlying medical condition–diagnosed as epilepsy–but what transpired over the last three months of Sevak’s life speaks for itself.

Inside her house, away from the neighbours who have gathered, Pooja broke down, the stress of the last few months evident in her words. Her husband’s shop shut, there was no money coming, and they were finding it hard to ensure enough food for the family. Her biggest guilt, she said, was that her breast milk “dried up” and she could not give her son his top feed.

Pooja used to take her son regularly to the government-run anganwadi—or creche, although it is much more than that—near the house when it was still open. Jyoti Verma, an anganwadi worker, said Sevak was already underweight when they last measured him, but she could not weigh the child after anganwadis across the country shut due to the pandemic.

In Delhi, the order to close schools and anganwadis was issued on 6 March,

2020. Initially they were to close till 31 March, but their lockdown had not been lifted when this story was published. So far, only Chhattisgarh has decided to reopen its anganwadis.

Long-Term Impact Of Closed Anganwadis

“Post the pandemic and the lockdown, the biggest impact has been due to a lack of food reaching families, communities,” said Sumitra Mishra, executive director, Mobile Creches. “In addition, the meals that children and pregnant women were getting at the anganwadis are no longer available. This multiplies hunger. We are seeing more cases of diarrhea and other illnesses due to constant nagging hunger.”

Sounding part apologetic, part defensive, Jyoti explained how difficult it had been to monitor children registered at her anganwadi.

“I did go twice or thrice to check on him but it was not possible to take his weight as during this period I can’t enter homes,” she said. Till date, the government has provided no protective gear to anganwadi workers like her.

The anganwadi was established under the central government’s Integrated Child Development Scheme nearly 45 years ago and is now one of the world’s largest early childhood development programmes, providing supplementary nutrition to children under six and pregnant and lactating women, apart from other services, such as early education, immunization, monitoring of health parameters.

Those delivering these services–the anganwadi workers–are trained women from the community. More than a million anganwadis across the country are among India’s frontline health workers, serving over 80 million children younger than 6 years and over 19 million pregnant women and lactating mothers.

Right-to-food activists and nutrition specialists have warned of the impact of a prolonged disruption to this key programme. It is now six months and reports from across the country are chronicling adverse health and nutrition impacts of the shutdown, unfolding at a time when nearly 20 million Indians below 40 years lost jobs (between April and July).

The Impact On Children, Pregnant Women And Nursing Mothers

In the course of reporting from five settlements across Delhi, it was clear that the impact of the shutdown is, predictably, being felt by young children, pregnant women and nursing mothers.

Madan Lal has worked with anganwadi workers in the area for the past three years as project leader for Mobile Creches, an NGO that has been active in the field of early child development for over 50 years.

“We may not be able to prove that Sevak’s death was caused by malnutrition, said Lal, “but our experience shows that a trained anganwadi worker can help look out for signs of weakness, illness and can step in to help a mother cope in situations like this.”

Another Mobile Creches worker, Geeta, said Sevak was already listed as atikuposhi or acutely malnourished–a category that is normally monitored closely and given supplementary feeds in an anganwadi. This became impossible after their closure. “We had made steady gains in both malnutrition and immunisation coverage,” said executive director Sumitra Mishra. “With the closure of anganwadi services this is a big danger.”

In Delhi, each child under six was supposed to be given the following rations every fortnight:

-

Wheat dalia Plain – 1,300 gm

-

Black channa raw – 260 gm

-

Jaggery – 130 gm

-

Roasted Bengal gram – 130 gm

-

Total grams of food: 1,820

Pregnant and lactating women were also sanctioned the same ration, 1,820 gm or 1.8 kg of food, with the amount of dalia increased to 1,690 gram. But these measures are not proving to be enough.

‘You Tell Me, Does This Look Enough’

A lane away from Sevak’s home Suman holds up a small packet of channa given as part of the rations.

“Sometimes, we get the packets every two weeks, sometimes in 20 days,” said Suman. “You tell me, does it look enough?” Her husband Vivek used to carry sacks at the vegetable mandi, but even the demand for such labour has dried up.

Their ration card allows them a subsistence diet, but that is not proving to be enough for her one-and-a-half year old daughter Lakshmi, who weighs 6.5 kilos. She is malnourished, according to World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines.

While the anganwadi was still working, Lakshmi’s condition had actually been improving and she had emerged from a more acute category of malnutrition. Now, that is slipping.

Vivek and Suman are among the fortunate ones who have a ration card. Preet Lal and Lakshmi moved into this colony a year ago from Uttar Pradesh. Dependent on manual labour for a living, they have found work increasingly hard to come by.

Lal and Lakshmi’s six-month-old daughter Tulsi had all the corrosive signs of hunger—bulging eyes, protruding belly, legs that are disproportionately tiny and frail.

“I’m scared to put her down for even a moment,” said Lakshmi, who carried her close, fearful of losing her.

As Lakshmi spoke, a group of women gathered around to express just how desperate their lives had become. Like many other women in this neighbourhood, Reena had started recycling waste ever since her husband had been unable to find work. It was a grueling task, which involved stripping the outer rubber casing of tyres to access the wire inside.

The wire must be ripped out bit by bit. A kilo of the wire will fetch Rs 10, but the wire is lightweight and three people working all day may together end up earning Rs 10 to Rs 20.

Reena has four children. The two under six used to go regularly to the anganwadi. Today, she struggles to feed all four,

“When those tiny packets of food come once in 20 days, I have to give all four of my children a little gur from it and it finishes in two days,” she said.

A Precarious Situation Is Exacerbated

The closure of the anganwadis has exacerbated a situation that was precarious to begin with. A 2019 survey by Mobile Creches found 47% of children in Shahbad Colony were underweight, as contrasted with the national average of 27 percent.

Clearly, the anganwadis were no magic wand, but they provided a critical input in a bleak scenario.

At the VP Singh camp in South Delhi, 30 km away, the higher incomes of residents is visible in the size of homes. Many here were employed on regular salaries, in small companies, factories or as government sanitation workers but have lost their jobs in the past few months.

Umda Devi’s husband Arun Paswan was a sweeper at an Okhla company, which has shut down. They have three children but with no income coming in they are finding government rations inadequate.

There is nothing unique about Umda’s situation. Her neighbour, Sunita Jha, comes out with her grandson, Prince Kumar Jha, who is almost nine months old. He was 800 gm when he was born. His weight, as measured by the workers of the Mobile Creches, is 5.75 kg, which continues to place him in the WHO category of acute malnourishment.

Another resident, who used to work for a courier delivery service, has also lost his job. His two-year-old son Shaurya is acutely malnourished. He was last weighed in February at the anganwadi, and at 6.5 kg figured among the acutely malnourished.

Both Prince and Shaurya needed close monitoring before the lockdown, and were not faring too well, despite support from the anganwadi and their current situation is even more precarious.

A few kilometres away, at Nardan Basti, Matri Sudha, an NGO, has been working on improving child nutrition, health and education. Its health and nutrition advisor, Arvind Singh, has been associated with the work for the past 10 years. He summed up the gravity of the current crisis.

“Concerted groundwork had ensured that the nutrition parameters were improving in a place like Nardan but in the past six months we’re watching that slip away,” said Singh. “We’ve been trying to help those without access to apply and get rations. We’ve been trying to distribute some food, but it cannot cover and compensate for some essential services–the anganwadi was that especially for the most vulnerable children.”

“It’s hard to see some of the gains made to secure better rights for children slip away,” said Singh.

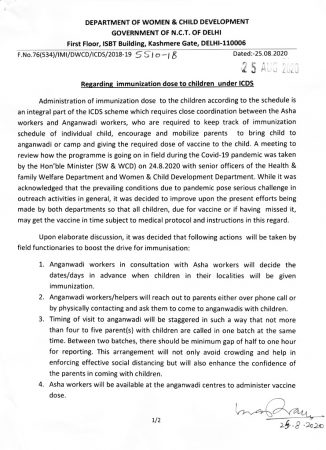

Matri Sudha, along with several other organizations doing similar work, has repeatedly pressed the government to start some of the critical anganwadi functions. On 25 August, the Delhi government announced (see below) that immunization programmes run through anganwadis would be restarted, but that will not address the issues of hunger and malnutrition.

Prasad emphasised that it was “possible and necessary” to restart anganwadi work on “growth monitoring and nutritional inputs”. Sumita Mishra of Mobile Creches said it requires governmental will.

Prasad emphasised that it was “possible and necessary” to restart anganwadi work on “growth monitoring and nutritional inputs”. Sumita Mishra of Mobile Creches said it requires governmental will.

That is not yet in evidence—except for gyms, pubs and malls.