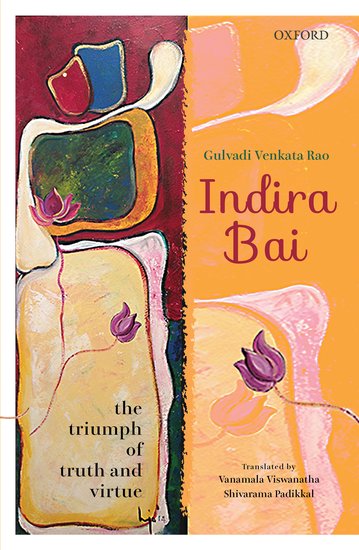

Indira Bai: The Triumph of Truth and Virtue is the English translation of the first social novel in Kannada by Gulvadi Venkata Rao. The translation, by Professor Vanamala Viswanatha and Professor Shivarama Padikkal, was recently published by the Oxford University Press, India. A woman-centric text, Indira Bai stages all the major debates of 19th century colonial India such as child marriage, widow remarriage, and women’s education. The text and translation make use of multiple languages as in real life. Vanamala Viswanatha and Shivarama Padikkal speak to writer Githa Hariharan about this complex translation process as well as the richness of social comment offered by the novel.

Image courtesy Oxford University Press

Image courtesy Oxford University Press

Githa Hariharan (GH): This is an extraordinary effort for various reasons. One is the way in which the novel, and the translation, take on multiple languages: as in life, so in text. What are the strategies you decided to employ as translators to deal with so many languages — Kannada, Tulu, Konkani, Sanskrit and different ‘versions’ of English?

Vanamala Viswanatha and Shivarama Padikkal (VV and SP): Thank you, Githa. Yes, multilingualism is the bedrock of the cultural ecology of India. It is not only a feature of the present but a defining aspect of the very civilisation of India. The coastal region of Dakshina Kannada provides a superb example of this phenomenon as it is marked by an intricate pattern of multilingualism in which several linguistic and religious communities jostle together within a hundred-kilometre radius. It is not merely a multiplicity of languages; these languages live, thrive, and fight in a complex web of social hierarchy.

In order to capture this socio-linguistic uniqueness, we, the team of translator(s), editor, and copyeditor, decided to evolve a new style while printing the text. Kannada, spoken by the Saraswat brahmin characters (the paradox is that Saraswat brahmins typically speak Konkani as their first language, and not Kannada), is the dominant language of the text. Where we have retained the Kannada words untranslated, they are indicated in single quotation marks as in ‘avva’ along with a gloss – ‘A colloquial way of addressing a woman/girl affectionately.’ Tulu, the language largely spoken by characters from the ‘lower’ castes, is marked by a single asterisk. Konkani, more specifically ‘Christian Konkani’, spoken by the two policemen, is established by the use of double asterisks. Sanskrit, the language of religious/cultural pursuits, is set apart by the use of italics. Finally, the use of English in the original Kannada text, is indicated by the use of small caps in the translation. This code-gliding between Kannada and English is particularly significant as it serves both the satirical intent of the novel in ridiculing the ultra-modern, phony ways of city youth as well as the representational needs of the narrative when it refers to the onset of colonial modernity in a local community.

GH: Still on languages, the multilingualism is not just rich in the sense of diversity, but also in terms of power structures — divisions of caste and class. Could you talk about this aspect of hierarchical use of language in both the text and in real life in the region?

VV and SP: Right through the text, Gulvadi uses Konkani, Tulu, and English to mark the social difference among the characters. Those lower down in the caste/community hierarchy, holding lower order occupations, speak in Konkani or Tulu. The English-educated youth speak a code-mixed Kannada sprinkled with English words. Some critics have attributed this mimesis to the compulsions of the social realist thrust of the novel. But such a reading ignores the text’s basic intent to construct in and through language(s) the imagination of a new community.

In fact, all the main characters hail from the Saraswat community which, in real life, speaks Konkani as its ‘mother tongue’. But, in the novel, they speak in Kannada, and not in Konkani. Among the languages of the Kannada region (the present state of Karnataka was formed only in 1956), historically, Kannada was the privileged language of cultural production. Thus, the Saraswat brahmin characters who are the protagonists of the text get to speak the language of power. The ‘lower’ caste/community characters speak among themselves either in Tulu or Konkani. Often these characters from the lower rung of society speak reverently about the protagonists Indira and Bhaskara as ideal characters; their gossip about the important characters takes the form of public commentary either endorsing the secular ethos of the emerging, English-educated, Saraswat brahmin group or disapproving the actions of mindless traditionalists like Bhima Rao and Amba Bai, or the immorality of the head of the Santamandali, or the actions of the shallow reformists. The choric voice of the ordinary people, used by the author to clearly mobilise public opinion for his tirade against degraded religious practices, offers a powerful critique of his society at that point in history. In the text, he brings alive this critique by translating lower caste speech in Tulu and Konkani into Kannada. As Padikkal (Early Novels in India, ed. M Mukherjee, Sahitya Akademi, 2002) has argued, the multilingual code deployed here writes in a new hierarchy of Kannada society in which the modern yet nationalist identity of the Saraswat community is constructed and valorised.

GH: There is also variety in terms of using genres such as prose, poetry, proverbs and so on. Would you link this with the social practices in coastal Karnataka at the time? Also, is this a challenge with many of our Indian texts as far as the translator is concerned?

VV and SP: Drawing from diverse centres of culture, Gulvadi’s text creates a space in which a variety of cultural forms and texts clash and blend. Various episodes from the art form Yakshagana Talamaddale, which belongs to the ‘little’ tradition, are deployed not only to represent the villain’s emotions, but also to provide an ironic effect. In the wake of his acquittal in a criminal case for murdering Sundara Raya, Bhima Raya presents the episode of ‘Vali vadha’ (The Slaying of Vali, in which Rama kills Vali through deceit, in order to win over his brother Sugriva), playing the lead role of Bhagavata, the chief narrator. While singing the song depicting Rama’s cowardly act of killing Sugriva slyly, Bhima Raya sweats profusely, stutters, and falls in a faint. The use of this art form is as much a critique of the character as a self-reflexive comment. The modern perspective projected in the novel perceives this traditional mode of entertainment to be crass and fit only for villains to pursue, whereas the shobhane wedding songs, part of the ‘Great’ tradition, sung by women at Indira’s wedding to Bhaskara, are celebrated in the novel as they glorify the ideal relationship of the couple.

Thus Indira Bai stages its cultural politics through its unique textuality. This can be a challenge for translators as well as readers in equal measure, since reading or translating such a text demands more attention and diligence. Given that the novel as a new genre was shaping up just then, Indira Bai had to simultaneously establish the form, the telling, the characters, and their speech. The text also bears witness to a literary culture in transition from the oral to the written, from the performative to the literary, perhaps a feature common to other Indian literary cultures. While the dominant mode of narrative is befitting the novel, the text also deploys drama and poetry, (evident in the use of dialogues, songs and chants) genres that marked the Kannada literary production in earlier centuries.

Translating this kind of a polycentric text can be quite a task for the translator. In particular, proverbs, the hallmark of oral tradition, do not easily move out of their natural habitat. It doesn’t work to replace them with possible equivalent proverbs in English. So we have translated them as literally as possible, signalling their presence with quotation marks. These proverbs are a crucial aspect of the social anthropology of the community portrayed by the novel. The text has sentences and paragraphs that run to two pages. Where we felt the narrative was getting cluttered, we have broken the text into separate paragraphs for greater ease of reading. Translation is, after all, a process where, as a translator, you walk the tight-rope between a commitment to the integrity of the text and its communicability to a contemporary readership.

GH: Coming to the text itself: a layperson’s knowledge of the reform movement of the time is obviously incomplete. I was struck by the influence of the Brahmo Samaj in the South. How did this happen? I also recall reading, in the Tamil context, public discussion in journals and papers about the need to educate women, but perhaps more important for us, exactly what this education can do. (Help educate children, be an intelligent partner to the husband etc — in short, reform with clear parameters from our point of view). Would you set the reform and reformist debate background for us in the case of Indira Bai?

VV and SP: The establishment of the Basel Mission schools in 1836 in the region was a major catalyst in radicalising the youth of the Saraswat community. Along with translating Christian tracts, the Mission also published books on science, geography, history and biology, thus opening the doors of western knowledge to the local populace. The modern sensibility imbibed through English education transformed young men such as Ullal Raghunathiah and Bharadwaj Shiva Rao to question the value of traditional institutions such as the religious mutts. But as Dr. Viveka Rai points out, these educational activities went along with the mission of conversion to Christianity. As a reaction to missionary conversions and to prevailing colonial tendencies in the public sphere to desecrate the ethos of Hinduism, a branch of the Brahmo Samaj, which had upheld the spiritual superiority of India, was started in Mangalore in 1870. Several thinkers, lawyers, and writers, chiefly from the Saraswat community, led this movement for social reform.

Interestingly, K Veereshalingam Pantulu, who wrote Rajashekhar Charitamu (1880), the first social reformist novel in Telugu, and had visited the region around this time, seems to have been a strong influence on the budding writers of Mangalore. Drawn to the tenets of the Brahmo Samaj, Pantulu had worked for social causes such as widow remarriage, women’s education, and anti-dowry campaigns. Gulvadi’s work needs to be seen against this background. On the one hand, the English-educated Gulvadi worked as a police officer in the colonial administration; on the other, he was profoundly influenced by the philosophy of the Brahmo Samaj. It is clear that Gulvadi’s work was an amalgam of both these streams that defined the very notion of Reform at that time.

As most of the reformists hailed from the upper castes, the upper caste Indian woman became the site on which the agenda of Reform was launched. Whether it was child marriage, widow remarriage, or women’s education, all these issues got articulated from an upper caste, male perspective. Women’s education was desirable if it could help women become modern and intelligent partners to their husbands, to run the household more efficiently and tastefully. Indira, who can read Sanskrit and English equally fluently (much like Chandu Menon’s eponymous heroine Indulekha in the Malayalam novel) becomes the quintessential New Woman in the modern nation of India at the turn of the century. While most of the social reform novels in Indian languages discuss the issue of widow remarriage, Indira Bai is the first Indian novel in which a widow remarriage becomes an actuality, delineated in vivid detail, with a stamp of total endorsement by the narrative.

GH: Since language as a social marker is so strong in the book, inevitably I have to ask about English as a vehicle for mobility and even emancipation. It brings along the whole baggage of going abroad, hence the fight against losing caste by crossing the waters; civil services; Indira getting new ideas by reading even basic ‘padri’ books; Christianity; and of course, for us in retrospect, the complex of reform/ progress while in some ways becoming ‘comprador’. At another level, it also brought to mind one strand of the more recent caste movements’ view, that English is a more liberating choice for dalits with other Indian languages — or ‘mother tongues’ — carrying so much casteist baggage.

VV and SP: The text showcases two, somewhat ambivalent, facets of English: the face that superficially mimics the language and the ways of the English as deplorable and hence such phony behaviour comes in for sharp ridicule; the other face that has imbibed the liberalism of the west after carefully weighing the pros and cons, and integrating it with what is defined as dharmic in the Hindu fold — as exemplified by Indira and Bhaskara — is glorified in the narrative.

There is a charming scene in the novel where Indira is reading books and her mother asks:

“What kind of books do you read?”

“Until yesterday, I was reading Stree Dharma Neeti. Right now, I’m reading Aesop’s Fables.”

“Aren’t those books printed by Christian padres?”

“I don’t know.”

“Those books are printed to defile our caste practices.”

“There was nothing that even vaguely looked caste polluting in any of the books I read. Also, can one lose one’s caste by merely reading a book?”

“There are things in those books which are against our religion.”

“Not in the ones that I read. They give useful ideas on how women should conduct themselves in the house of their birth as well as in the husband’s house.”

The polyphonous sign called ‘English’ is thus deployed astutely to recast a new social imaginary which is best represented through a reconstituted image of the modern woman who can read, who is made modern and rendered anew through English education, while she is firmly grounded in a reformed and enlightened Hinduism.

Indira Bai is a text that argues for a ‘wisdom/sense of discrimination appropriate to our times.’ When the winds of western knowledge and liberal thought blew powerfully over our land, one had to respond to it by exhibiting a sense of discrimination that keeps the best from the native land as well as the foreign power. The colonial critique of India, which justified their ‘civilising mission’, condemned the treatment of women in the name of the scriptural tradition. The nationalist response was to reform tradition through a process of modernisation. This compulsion created the image of the new, upper caste, English-educated woman who was superior to all women in other castes/classes/communities. As Partha Chatterjee has demonstrated, the new patriarchy invested the upper caste woman with the ‘honour’ (read, ‘burden’) of representing a distinctly modern yet deeply nationalist culture.

But has ‘Project English’ been liberatory for women in India? Has it empowered all women equally? These questions have been robustly tackled by subsequent feminist debates in India.

GH: Finally, the history of the book since it was written, in particular, the journey of its translations. The first translation was by an Englishman, a colonial, am I right? Would you trace the translators’ readings since then in broad strokes?

VV and SP: As well-known Kannada literary historian Havanur (1989) notes, within a few months of its publication, Indira Bai had sold over 800 copies, which was a record for its time. This ‘impressive’ figure has been attributed to the fact that the police personnel, since the novel deals with a police case, were given a discount of 25% on the total price of Re.1 (one). This, coupled with the readers’ responses published in the local newspapers in English, and the fact that M E Couchman, a local administrator, translated it into English within the next four years, leads one to conclude that Indira Bai was a fairly popular novel. While The West Coast Spectator described it as ‘a novel with a purpose’, The Madras Standard, The Indian Social Reformer, and The Madras Mail (See Appendix of the book) commented on the social reformist thrust of the novel.

However, in the absence of an extensive network for distribution, the reach and influence of the text was limited to the region of South Canara. Hence until its second edition was brought out in 1962, the rest of Karnataka was not quite aware of this novel. This novel had not found mention even in E P Rice’s A History of Kannada Literature, published in 1921. Noted writer Shivarama Karantha has commented on this fact of scholarly neglect in his foreword to the second edition. But since then, scholars and critics have celebrated the work for its stellar qualities of social realism, incisive satire, rich detail, and progressive thrust. The Government of Karnataka reprinted the novel, selling it at very affordable prices (Rs 8.50) in 1985, which further popularised the novel in the Kannada world.

Given that the novel as a genre was just beginning to take shape in Indian languages in the 19th century, Indira Bai illustrates with incredible vividness the baby steps taken by modern Kannada culture and its writing practices in exploring a new literary form. The text dramatises, through its use of language and choice of textual strategies, the Saraswat community’s journey of transformation from being a world of unshaken faith in customs, rituals and beliefs, to a modernising world gradually encroached by western education, values, medicine, law, and police. Therefore, the use of linguistic and literary devices in the text is not merely a flourish; they have a defining role in constructing the meaning of the text.

Hence, the translation reflects the changing face of this narrative closely. The text in English does not have the unbroken flow of a modern novel, but it is marked with shifting discourse types. Like a Harikatha discourse, the novel draws into its fold, various art forms from the performance traditions of the Dakshina Kannada region — yakshagana, taala maddale, folk song, and traditional song which signal the stronghold of tradition. Quotes from medieval Kannada poetry and chants from Sanskrit, two languages with greater cultural capital in the linguistic mosaic of the region, are used to represent the eternal relevance of the scriptures. As our purpose is to present the history and culture of the times, the critical anthropology of the Saraswat social community, and the emerging poetics of the Kannada novel, we have tried to retain a high level of literality in the translation.

As mentioned before, an earlier English version translated in 1903 by A E Couchman, an Assistant Collector in the colonial administration and a superior of Gulvadi, is already available. We have provided his preface and a few responses to the translated novel in order to give a sense of the time and clime of the first version. Like Couchman, the first translator of the novel, we would also like to say, ‘… the translation follows the original as closely as possible, even at the risk of occasional stiffness….’, but with a difference. Where he sounds apologetic, we hope, we do not. For, we wish to affirm the use of literality as a potent technique of resisting the homogenising power of English that tends to erase cultural difference.

Every age chooses and translates the texts it needs for its own purposes. We have embarked on this project as Indira Bai is a significant milestone in the history of Kannada. Equally important, the novel in its English translation will add to the burgeoning wealth of the emerging field of Modern Indian Literature. It is instructive to recall Aijaz Ahmad’s argument (In Theory, 1990) that the category of ‘Indian Literature’ becomes possible today only through translations into English; however, the Honourable Home Minister might rule differently on the issue. Our hope is that this translation of Indira Bai, a small step in opening up the Kannada world of 19th century to a pan-Indian readership, will lead to strengthening the field of Modern Indian Literature (in contrast to Indian Writing in English, an allied field constituting a different thematic and problematique) and provoking debate and dissent on issues that mark our post-coloniality — region and nation, tradition and modernity, gender, caste, and community, along with the complex, intersectional thrust of our self-fashioning in a globalised world.