Some stories live forever, some die in time and a few change so much over the years that they ultimately become very different from what they were when they were born. And there are also stories that never come to life. I know one such story. It haunts me, especially since I am the only person who knows it and only I can give it life. But I am no storyteller. I don’t have the skill, unlike the sutas, who learn the skill when they are still in their mother’s wombs. There is this too, that I was part of the story, and that I played a not very honourable role in it. So why do I desire to tell it? Perhaps because I don’t want to carry the burden of this untold story any longer. I am a sick man, I know I am not very far from my end. I have to speak, I need to speak.

Let me begin. Oh, I forget. I have to first say who I am. I am Galava, a poor Brahmin student. I was, at one time, a student of the great Vishwamitra. This is my only distinction. Vishwamitra is known for his temper and his curses. Which is why people, even kings and princes, were afraid of him. In my story, however, it was not a curse, but a boon, that created havoc. I suddenly realise I don’t know whose boon it was; I have not thought of this until now. I was told there was a boon and I accepted it. Now I wonder – whose boon was it? But I am getting far ahead of myself, I should start at the beginning.

The beginning? Where is it? Did it begin with Vishwamitra and me? No, I think it goes way beyond us. It began with three people: King Yayati, Sharmishta, daughter of the King of Asuras, and Devayani, daughter of Shukracharya, the Guru of the Asuras. I must not forget that there was a fourth person in the story as well. Shukracharya himself. A learned and wise man, but with one fault. He loved his daughter immoderately and never denied her anything; she never knew what it was to not have what she wanted. Kacha was her first defeat, Kacha, who came to her father as a student, Kacha whom she began to love and desired as her husband. But that is another story, it has no place here. I can only say that having lost Kacha, Devayani made sure that she would not lose her next victim. Victim? Is that the right word? I think so. Yayati did finally become a victim. Or did he?

Let me get back to my story. To how Devayani met King Yayati. He was out hunting when he heard cries for help coming from a well. It was a female voice. If Yayati had known what was waiting for him in the well, he would have walked away. But how could he have known that? And as a Kshatriya King, he could not abandon someone, specially a female, who seemed to be in distress. He did what he had to. He went to the well and helped the girl out. This was Devayani.

Devayani had seen his dress, the entourage that stood respectfully at a distance from him and knew he was a King. She immediately grasped at her opportunity. ‘You held my hand,’ she said, ‘Now you have to marry me.’

Anyone can imagine what this did to Yayati! He had done his duty as a Kshatriya, that was all. And now suddenly this proposal.

‘But … but you don’t even know who I am!’

‘You are a King.’

‘Yes, King Yayati,’ he blurted out.

‘You held my hand. A man has to marry the girl whose hand he holds.’

Was there such a rule? The King was too confused. He now tried another defence. ‘But I don’t know who you are.’

‘I am Devayani, daughter of Shukracharya, guru of the Asuras.’

Everyone knew Shukracharya’s love for his daughter, his anger if she was crossed. Yayati, like so many, feared the deadly curse of the rishis.

‘You are a Brahmin girl … I am not sure your father … ’

‘My father will never say no to any man I choose. But if you refuse me …’

A veiled threat. No, a not-so-veiled threat. Yayati knew he was trapped.

And so he married Devayani. But it was not enough for Devayani to be Queen. She had to punish Sharmishta. Did I forget to say that it was Sharmishta who had pushed Devayani into the well in a fit of pique? It was the result of a childish spat between Devayani and Sharmishta, one of those ‘my father is greater’, ‘no, my father is greater’ kind of arguments, neither of the girls willing to give up. Devayani did not forget this. She now made her father tell the King that Sharmishta had to go with her, Devayani, no, Queen Devayani, as her maid. The King was angry, but he needed Shukracharya. Sharmishta however made things easy for her father by saying she would go with Devayani. She realised she was being punished for her childish act of spite, for her arrogance. She had learnt her lesson – unlike Devayani who never learnt anything. She missed no opportunity to insult and humiliate Sharmishta, to show her power. She should have been careful, for Sharmishta was a beautiful girl and her helplessness and gentleness added to her charm. The inevitable happened. Yayati, who always had an eye for women, found his sympathy for Sharmishta soon changing into love. They got married, a secret marriage.

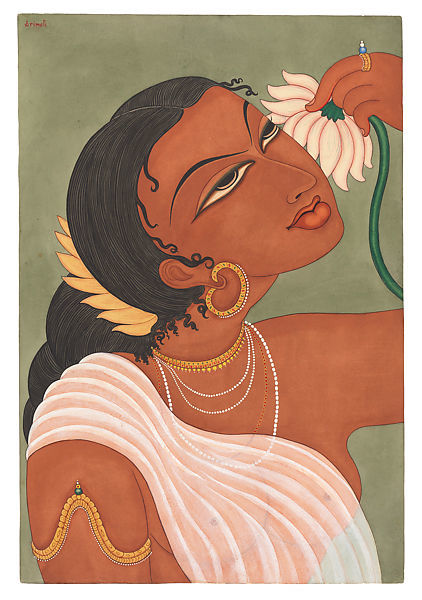

How long could it remain a secret? The news spread through the palace, through the kingdom. When Devayani came to know of it, she sobbed, she raged, she threatened she would tell her father; but finally she had to accept the marriage. Her jealousy, however, never abated, it never ceased. She could not tolerate the fact that the King spent more time with Sharmishta than with her, she was full of anger that Sharmishta had three sons while she had only two. That she had one daughter, Madhavi, while Sharmishta had none, was something she took no note of. Daughters didn’t matter, daughters didn’t count. And so there they were, a man and two women. This is where I entered the story.

What have I a poor Brahmin to do with this story of Kings and Queens and Princesses? Let me explain. I have said it, have I not, that I was Vishwamitra’s pupil? Well, at this time, my studies had come to an end and I had to go away and take on my worldly duties. Before leaving I had to give Vishwamitra his gurudakshina. I had agonised over it – what could I give a man to whom Kings and Princes came with rich gifts? What did I have which was worthy of him? I could think of nothing. There was nothing. I went to my guru, prostrated myself before him and said it was time for me to leave the ashram.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘time for you to go back into the world.’

‘But I have to give you my gurudakshina.’

‘What are you giving me?’ he asked. Then, ‘what can you give me?’

‘You know I am a poor man.’

‘So why speak of gurudakshina? You can go. After all, I have not been able to teach you much.’

After insulting me, contemptuously asking me what I could give him, was he ridiculing me, saying that I had learnt nothing? I admit I was a little slow, but I got there in the end. And what I learnt I never forgot. Maybe he was criticising himself, that he had not been a good teacher. No, he would never do that. His words I have not been able to teach you much were meant for me. It hurt me, it angered me. I had worked hard, I had memorised so many shlokas …

‘But I have worked hard. I have never shirked my duties.’

‘That’s right. I agree you have worked hard.’ It seemed to me that he was speaking of my manual duties in the ashram. ‘And you have nothing to give me. So go.’

It made me more determined to prove I was not as unworthy as he was making me out to be. That I was like all his pupils.

‘How can I go without giving you your gurudakshina?’

‘What can you give me?’ he asked again.

‘Whatever you ask me.’

He closed his eyes for a minute. He did this when he was irritated, or when he was trying to control himself. I was frightened. What had I done? What was he going to ask me?

‘All right then. You will bring me as gurudakshina eight hundred horses, horses white as milk, except for one ear which should be black as the night.’

My mouth must have fallen open. Eight hundred horses? White as milk, with one ear as dark as the night? What was he saying? Where could I, a poor Brahmin, get them from?

‘You can’t do it?’

He’ll curse me if I say I can’t. These rishis and their curses!

‘No, no, I’ll get you the horses.’

‘Go, then. And don’t come to me until you have what I have asked for.’

Eight hundred horses. Milk white horses. And with one ear black as night. Where could I get them from? Were there such horses in the world at all?

‘You’re stupid,’ my friend said to me when I went to him in despair. ‘When he said he didn’t want anything, you should have given him some flowers, fruits, honey, touched his feet and come away.’

‘But I didn’t do that, did I? No point speaking of what I should have done. I need your help. We’ve been friends since childhood. You got me out of trouble many times when we were boys. You can’t deny me now.’

He didn’t. ‘I know,’ he said, after we, or rather he, had searched for some way of fulfilling my guru’s wishes. ‘I know what you can do, the only thing you can do. Go to a king. Only kings have horses – though they may not have the kind you want. Go and ask. What do you lose?’

‘Why would they give them to me?

‘You’re really stupid. Because you are a Brahmin. You know how these kings are. They can’t say no to a Brahmin. It’s one of the things they are taught in their cradles. Go,’ he said, ‘Go to our King Yayati first.’

While I waited for Yayati in his public hall, I looked around me and I saw no signs of a rich king. He must have emptied his treasury for his pleasures, he won’t be able to help me, I thought. When he came, I saw that he looked dissolute, coarse. Not the handsome young king his people had admired. This was a man who had spent not only his riches, but himself as well.

Nevertheless, he listened to me patiently and when I had done, he said, ‘I don’t have eight hundred horses, let alone the kind you want.’

‘White, with one black ear,’ I muttered.

‘I would have helped you if I could. You are Vishwamitra’s student, I have to help you. But I don’t have what you want.’

‘But it is for my gurudakshina,’ I said, bringing in Vishwamitra once again.

‘I understand. Let me think.’ After a small pause he said, ‘Come back tomorrow. I will see what I can do.’

The next day when I met him, he was smiling which told me he had something for me.

‘I have found a way to help you,’ he said. And before I could express my gratitude, he told me how he was going to help me.

I could not understand him at all. His daughter Princess Madhavi – what had she to do with my predicament? What was he saying? Take her with you? How would that help me?

‘Don’t you know? She has been given a boon.’

A boon that she would bear only male children. And that her sons would become Emperors. ‘And,’ he said ‘she will become a virgin each time after she has a child.’

He saw my bewilderment, he realised this made no sense to me. How would this help me? A little impatiently, irritably, he said, ‘Take her with you. Go to kings who have the kind of horses you want.’

‘Milk white with one black ear.’ I chanted the words like a mantra, as if they would give me what I wanted.

‘Offer them Madhavi in exchange for the horses. Tell them about the boon. Nobody will refuse you.’

I felt as if I was in the middle of a story I could not understand. A father giving his daughter away? It was only in a marriage that … Was he telling me I should give her in marriage to a king who could give me my horses? But what right had I to give away a girl – and I a Brahmachari as yet?

He saw my hesitation. ‘I had promised you I would help you. I have to keep my word.’

And I had to keep my word to Vishwamitra. But to use a girl? Even while I was in a state of shock, the Princess came out. He must have asked her to come.

‘Here she is,’ he said. And while I remained rooted to the spot, he said, ‘You better leave right away.’

I scarcely looked at her. I was still in a daze at what the King had said. In any case, he almost hustled us out. The Princess came with me. What had he told her? The question hammered in my mind. What had he told her that she came so willingly with me? I was afraid to ask her. What if he had not told her the truth? What if I let it out and she walked away? What about my gurudakshina then? But to give a girl, a Princess, to a man? Perhaps he meant in marriage, he must have meant marriage. I cheered myself with the thought. Surely no father would be so vile as to hand over his daughter to just anyone!

In spite of all these doubts, I took Madhavi to the Ikshvaku king, who, I had heard, had the kind of horses I wanted. He received us with courtesy. After all, I was Vishwamitra’s pupil and I had come from King Yayati.

‘What can I do for you?’ he asked politely

I told him about my need for horses. Milk white with one ear as black as night. They would be my gurudakshina for Vishwamitra.

‘Yes, I do have such horses. But it is a big thing you are asking. These horses are rare and valuable. What will I get out of it?’

I found it hard to answer him, I could not find the words to say that I was giving him Princess Madhavi in exchange. But I had to tell him about it. And so, a little desperately, I told him about Madhavi. I saw the shock on his face. I went on in a rush, afraid that if I did not say it now, I never would. I told him about the boons. His face changed. He listened to me in silence. When I had done, he asked, ‘And you say Yayati himself gave her to you?’

‘Yes.’

‘To exchange for the horses you want?’

‘Yes.’

‘Where is she?’

‘She went to the women’s rooms.’

He clapped his hands, called a serving man and asked him to get Madhavi from the women’s room. The moment she came in, the atmosphere in the room changed. The King turned away from me, as if I no longer mattered. ‘Welcome, Princess,’ he said, ‘welcome to my palace and my home.’

I could see he was pleased with her. And she…? Yes, she too seemed pleased. This king was a young man, well, not very young, but not old, either. And he had a pleasing face, he seemed gentle.

‘Go in and rest,’ he said. ‘The women will look after you.’

And then came the worst of it. ‘The horses?’ I asked.

‘The horses? Oh yes, the horses. I will have them brought to you. But there is one problem. I have only two hundred horses of the kind you want. Not eight hundred.’

‘What? But I need eight hundred. I can’t leave Princess Madhavi here unless I have eight hundred horses.’

What was I doing? Bargaining with a woman’s body, no, a girl’s body. But I had no choice, I could not give Madhavi away for only two hundred horses. I had given Viswamitra my word. I needed eight hundred horses.

Finally we struck a deal. He would give me his two hundred horses and I would leave Madhavi with him – but only for a year.

I left in a hurry. I did not want to see Madhavi or talk to her. True, there was little chance of her coming out to meet me, but I was not going to take even the smallest chance. All the way home, I thought, what had I done? What had I done? But it was not me, it was her father. Which was neither comfort nor consolation. Thoughts were galloping in my mind like horses. Horses white as milk with one ear black as night. What have I done, what have I done?

I went back after a year. The King received me at once. I could see he was very pleased with himself.

‘She has given me a son,’ he said right away. ‘A beautiful son.’

Had he forgotten I had come to take her away? ‘You remember our agreement?’ I asked.

‘I remember. But can’t you leave her …?’

‘ No. You gave me your word.’

‘All right. But I keep my son.’

Keep the baby? I had not thought about that.

‘You didn’t say anything about the child. He is my son, I keep him.’

I gave in. The King went away and Madhavi came out to me in a short while.

She looked around. ‘They told me the King wanted to see me?’

‘Not the King. It was I.’

‘Oh! What is it?’

‘We have to go.’

‘Go where?’

This was going to be hard. I cursed the King for running away and leaving me to explain it to this girl.

‘Just come with me. The King says I can take you away.’

‘But I thought …? He called me his Queen.’

I had to tell her the entire story now. Her father obviously had told her nothing. Or had told her a lie. I cursed him too and tried my best to tell it to her in a way that would hurt her the least.

She listened quietly. When I had done, she asked, ‘So you gave your guru your word to get him eight hundred horses?’

‘Yes.’

‘And my father gave you his word he would help you?’

‘Yes.’

‘And so he gave me to you. To be exchanged for horses.’

I said nothing.

‘And now we go – where?’

‘Another King The King of Kashi. I have heard he has such horses.’

‘And you will give me to him in exchange for his horses?’

I was silent yet again.

Suddenly her composure broke, a sob burst out of her and she said, ‘My baby? What about my baby? They took him away from me. I want my baby. I can’t, I won’t go without him.’

‘He belongs to the King. He is the King’s son.’

‘I gave birth to him. He is my baby.’ Her hands went to her breasts, heavy and oozing with milk as the damp spots showed. ‘I want my baby.’

She swiftly turned around as if to go back inside. In an equally swift movement, two of the guards barred her. She looked at me as if for help. I stood there, helpless, angry, miserable. And as she looked, from the men barring her way to me, still as a statue, it was like she understood something, something which might have taken her a lifetime to know otherwise. If at all. My eyes fell before hers and her hands fell from her breasts to her side. She looked smaller as if something had seeped out of her. Then the moment was over and she said, ‘All right. If we have to go, let’s go. Right away.’

We went to the King of Kashi. Once again it was the same story. The King had only two hundred horses. Once again I bargained with him. He finally agreed that Madhavi would stay with him only for a year.

‘And if she has a son? He will be mine?’

This was a King without sons. He would never let go of the child.

‘Yes,’ I said.

When I went back after a year the King was jubilant. He had a son, he gloated over the fact as if it was entirely his doing.

‘Why don’t you leave her with me for another year?’ he asked. ‘I need one more son. Just one son is not enough for a king. It is safer to have more than one.’

‘I will leave her with you if you give me two hundred more horses.’

‘I don’t have them.’

‘Then I take Madhavi away. We had agreed to this. You must keep your word.’

I had become more skilled at bargaining. I was hard and businesslike. How quickly one learns!

Madhavi came out. Inside I could hear a child screaming.

‘Let’s go,’ she said. ‘Quickly.’ As if she could not bear to hear the cries.

What am I doing? I asked myself once again. What am I doing? And yet, I went with her to the King of Bhoj. I didn’t have to explain anything to him. He had heard about her, about her boons, and the sons she had borne the two kings. He welcomed her with joy, he gave me his two hundred horses without hesitation.

When the year was over and I went to take her away, she was waiting. Someone had told her I had come. ‘Let’s go,’ she said quietly.

When we were on the road, she asked me, ‘Where now?’ As I hesitated, not knowing what to say, she burst out. ‘I will not go anywhere. I will not go to any King. I can’t do it. I can’t do it. Not any more.’

She sounded desperate. What had she experienced?

‘There are no more Kings with horses.’

Relief flooded her face. She immediately said, ‘Then let me go.’

‘Not the kind of horses I want,’ I added. ‘And I have only six hundred horses. I promised Vishwamitra eight hundred horses.’

‘And you have to keep your word.’

I said nothing. ‘So where are you taking me? Haven’t you decided?’

‘What did your father tell you when you came with me?’ I asked her suddenly

‘Nothing. Only to go with you. And to do whatever you asked me to do.’

‘And you came? You didn’t know me.’

‘I know my father.’

What did she mean by that?

‘And your mother? She said nothing?’

She was silent for a moment, as if thinking. Then she spoke in a kind of monotone, no expression in her voice or on her face.

‘My mother is an angry woman. She was angry that my father spent more time with … with my second mother than with us. To me she said, do what your father says. That’s all she’s always said to me. She is so frightened of displeasing him.’

‘And your boon?’

‘What boon?’

‘That you will bear only male children, that your sons will become Emperors?’

‘I never heard of such a boon.’

How could she not have? Was it a lie, then? I have had much time to think since then and I have begun to wonder whether what Yayati did to Madhavi was his act of revenge against Devayani for ruining his life. By making a prostitute of his daughter. Could a man be so vile? I have not lived much among men, so I don’t know. But I have begun to think that yes, Yayati had invented the boon so as to make her a woman every man would want. A woman who would have only sons, sons who would become Emperors. Who could resist such a woman? But what father would give his daughter to a man and say ‘make use of her’? I thought of my father with his daughters, my sisters. How protective he was of them, how he loved them. He always tried to give them whatever they wanted. And this man Yayati was a King. And what about the boon that she would become a virgin after a child was born to her? Had Yayati invented that too? I had not spoken to Madhavi of it. How could I speak to her of such a thing? But I could see with my own eyes that it was not true. I had seen her body become rounder, fuller, after her first son was born. More womanly. She was a woman now, not a girl. How could anyone believe that virginity could be restored to a woman after she had a child? Even if the body mimicked virginity, what about the woman’s mind, her emotions? What of the memories she had of sleeping with a man? What of her motherhood? I thought of her holding her breasts and crying out, ‘My baby, my baby.’ I was then, still am, a Brahmachari. What do I know of women? Or of mothers? My own mother died when I was only a boy. But I saw what it was to be a woman, a mother, I saw it on Madhavi’s face, I heard it in her cry.

‘I can’t do it,’ she said again. ‘Let me go.’

‘Where will you go?’

‘To my …’ she faltered. There was a long pause. I waited for her reply. ‘Anywhere. I will find some place,’ she said.

‘How can I tell Vishwamitra I have only six hundred horses?’

She shrugged.

‘All right. I will talk to my guru. If he agrees, I will take you wherever you say.’

When we reached the ashram, I left her again among the women and went to my Guru. I prostrated myself at his feet.

‘Get up, get up,’ he said testily. ‘Have you brought my gurudakshina?’

Old man, you pretended you wanted nothing. Now you talk of your gurudakshina without even asking me how I am.

‘No.’

‘Why?’ I could see an outburst of anger coming. He’s going to curse me, I thought.

‘There are no more horses.’

‘How many do you have?

‘Six hundred. If you could forgive me and take these …’

‘I said I wanted eight hundred horses and you promised me eight hundred. You should keep your word.’

‘But … but … there are no more horses.’

‘So?’

I told him then, I told him the entire story, from the time I went to Yayati till this moment.

He was silent for a few moments after I had done. Then he said, ‘If there are no more horses, there is the girl.’

‘Girl?’

‘Yayati’s daughter. You can give her to me for a year like you did with the kings. I will then forget about the two hundred horses.’

I could not believe it. A man considered so wise, so learned. His verses for the Rig Veda were famous, we students were proud of his achievement. Now he wanted a woman. No, a girl. He had three wives already, but he wanted Madhavi. I wished for the first time that I was a Kshatriya with a weapon in my hands, not a Brahmin spouting words that mean little.

But perhaps he didn’t mean it. No, he did, he was serious. I wanted to stop my ears, I wanted to curse him. But I was no Vishwamitra. I wanted to tell him I was going to send her back to her father. He could do what he wanted to me after that. But I said nothing. Old habits die hard. I could not so easily forget my years of obedience to this man.

I went to her and told her about Vishwamitra’s solution. She listened to me in silence. She was silent even after I had done. ‘He’s an old man,’ I said, trying to console her. ‘He won’t be …’ I could not find the right word, ‘… as bad … not like a young man.’

‘It makes no difference,’ she said wearily. ‘The King of Bhoj was an old man. He was no different. All men are the same in their urgency when they want a woman’s body. Kings, scholars, saints, ordinary men – what they want they will take. If they want a woman’s body, nothing else matters.’

I felt a pang of guilt, of shame, thinking of that innocent young girl I had taken away from her father’s home. This girl, this woman who spoke with such knowledge, such weary wisdom of men and their desires – how far she had come from that girl! And I thought, how can they even imagine she is a virgin, this woman who knows all about men, about their desires, about their bodies! A woman who has no expectations, no illusions about men. What boon can restore her virginity? I knew then that this whole world of curses and boons that we lived with was a falsehood.

‘Don’t worry about me,’ she said, as if she had read my thoughts. ‘I have learnt to separate my mind from my body. I can do the same with this old man. Your Guru.’

For a moment I thought – I will take her away from here. I don’t care about the horses and the gurudakshina, about curses and boons. Let’s go away, I wanted to say to her.

But what would that make of me? I would be just one more man like the others. A man who would use her as they had done. But I didn’t want sons, I only wanted …

‘Go away,’ I said to her suddenly. ‘Go away from here.’

‘Go where?’

‘Go to your…’ Like her, I faltered. I could not say ‘to your father.’

‘No. I have decided I will help you to complete your mission. It will be something I will have done. There’s nothing else,’ she said, spreading out her arms as if to show me the emptiness of her life. The thought of her children, the sons she had left behind, flashed through my mind. ‘And maybe I will do something wrong and he will curse me. I would like to be cursed that I will have no more children.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘You will not go to Vishwamitra. Tell me where you would like to go, I will take you there.’

Sharmishta, I thought, her other mother. She is said to be a kind woman. Why not take her to Sharmishta?

‘What about you? Your gurudakshina? And Vishwamitra’s anger?’

‘I don’t care about those things anymore.’

‘No, I will complete my job. So that you will have kept your word to your guru. After that …’ She said no more.

I could not move her. I left her there and went away. I never saw her again. I learnt that Vishwamitra had a son by her. He was ecstatic. A son at his age! I remembered the King of Bhoj who had also been triumphant at getting a son. My son, they said, all the men. My son. I also heard that her father Yayati took her home after her year with Vishwamitra. And, what amazed me, he had a swayamvara for her. A mother of four sons. But she would bear only sons. And she was a virgin, wasn’t she? Fools, I thought in contempt. Fools. I also heard, much later, that men flocked to the swayamvara. Every man wanted this amazing woman who bore only male children and became a virgin immediately after the baby’s birth.

My friend told me the rest. That she came into the hall, a garland meant for the lucky chosen man in her hands and standing in the centre of the hall, she looked at all the men who were there. Slowly, taking them in with a probing direct look. And then she threw the garland down, like a challenge to all the men, and walked out, trampling over the garland as she left. She walked away from her father’s kingdom, nobody knew where she went.

I don’t know what happened to her after that. Whether she went into the forest and lived in an ashram, or whether she went away from all human habitation and lived alone. I don’t know. I don’t want to know either. Does any man like to see the body of a person he has killed?