Image Courtesy: AP and Livemint

Image Courtesy: AP and Livemint

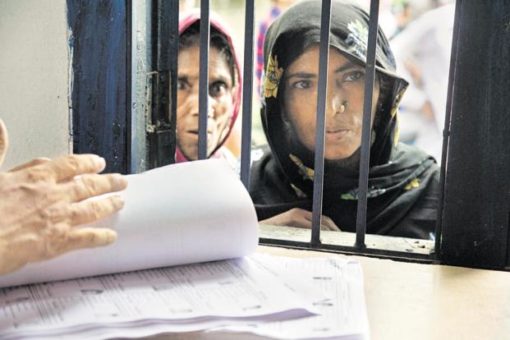

As the Assam government prepares to publish the final draft of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) on August 31, a humanitarian catastrophe of unprecedented nature is unfolding in the state.

The NRC updation exercise, sanctioned by the Supreme Court through a 2014 judgment, is aimed at identifying “illegal” immigrants from Bangladesh who entered Assam after 24 March 1971.

Currently, the whole process is in its “claims and objections” phase, as part of which the NRC authorities are addressing the citizenship claims of applicants whose names were missing from the second draft of the NRC list published last year July. Over 40 lakh applicants had been dropped from the second draft.

Alongside the court-mandated process of adjudicating claims of missing applicants, another parallel, and rather illegitimate, process is underway. According to reports in the media, applicants whose names had already featured in the second draft and those who had already attended multiple hearings after finding their names missing are being summoned for hearings once again at locations far away from their places of residence, that too at severely short notice.

It is unclear why this is being done, as the Supreme Court had already rejected a proposal for reverification.

The outcome? Total chaos, confusion, anxiety, road accidents, injuries and deaths.

What happened over the last few week is inexcusable and falls squarely on the Assam government and NRC authorities, including NRC State Coordinator, Prateek Hajela. Around three hundred people, many daily wage labourers, from two Lower Assam districts of Barpeta and Kamrup received “sudden” notices for hearings in Upper Assam districts that are around 300-400 kms away from their villages. As reported by The Indian Express, almost every single house in one particular village received these notices.

What followed was a human tragedy of devastating proportions – reeling under extreme panic, people hired all kinds of vehicles from buses to pick-up trucks to reach the hearing venues, often jam packed like cattle inside trailers.

As if that wasn’t enough, three of the vehicles met with road accidents, thanks to sleep-deprived drivers rushing at high speeds to ensure that the applicants reach their hearing venues on time. Photographs from one of the accident sites showed bloodied and partially-charred victims covered with hot peat on which their bus had toppled.

From the outset, the NRC process has been an arbitrary and exclusionary one. It is, by design, aimed at exclusion and not inclusion. At various stages of the process, the authorities, despite the apex court’s monitoring, have come up with obscure and confusing procedures by leveraging their bureaucratic autonomy.

The mad rush created for hearings, identification, verification and reverification – which only carry a mere possibility, not certainty, of inclusion – have driven many to great emotional, financial, physical and social pain and stress. Worse, the state and its institutions, including the apex court, have completely failed to ease the pain.

Truly, if there was one word that could aptly describe the NRC’s fallout, then that would be ‘anxiety’. The recent mass summons and the subsequent deaths and injuries on the road only reveal the sheer unjustness of the whole process.

The re-verification process that is currently underway, as part of which abrupt notices were served to hundreds over the last week, is in express contravention of a recent Supreme Court order, dated July 23, that rejected a plea by the Union government to undertake reverification. The latter had asked for a re-verification of “a limited percentage of the exercise done so far to take care of wrongful inclusions and exclusions.” Stating that the NRC authorities had already reverified around 27% of the applications during the claims and objections stage as submitted by Hajela in an July 18 report to the bench, the court said the following:

“[…] we do not consider it necessary to accede to the prayers for a further sample verification as prayed for on behalf of the Union of India and the State of Assam. No further orders in the matter would be called for at this stage.”

The ongoing re-verification process and the attendant inter-district hearings also violate the NRC authority’s own Standard Operation Procedure (SOP), approved by the apex court for the claims and objections stage.

The rules state that the summon notices must be served “at least 15 days prior to the date of hearing”, and if the notice reaches late, then “an alternative date of hearing will be fixed and fresh notice with 15 days time from its receipt will be ensured.”

It also says that the hearing venue must be a “a suitable place easily accessible to claimant or person objected upon”.

By forcing people to appear at hearing centres hundreds of kilometers away from their homes, that too at a day’s notice, the authorities are in contravention of the above rules.

These fresh notices may not be directly linked to the Supreme Court moratorium on reverification as against the central government’s appeal. But, in reality, one automatically leads to the other. In the claims and objections phase, people have been served two types of notices – RN1.1, which calls for the re-verification of the recipient, and RN 2.1, which calls for re-verification of the ‘legacy data’. In the NRC, ‘legacy data’ is a continuum of intergenerational and cross-family relationships.

This makes any kind of reverification proliferative by design – an inquiry of one link in the family chain would inevitably have to draw in other related links for examination. Thus, the 27% that Hajela claimed he had reverified must have led to reverification of other interlinked applicants, which could explain the fresh notices. In that sense, the government’s desire of reverification is already been fulfilled by the NRC authority, bypassing the apex court order.

One of the justifications provided for these fresh notices to people already included in the draft NRC is that the disposing officer adjudicating the claims and objections had certain doubts with regard to these individuals. But, only the officers know what counts as “doubtful” in such cases. It is such loose ends, inter alia, that provide sufficient ambiguity to the verification process for the whole NRC exercise to appear ideologically or politically motivated.

Further, one wonders why the state government decided to opt for reverification at this stage. After all, it had a range of options at its disposal to check wrongful inclusions during the course of NRC updation.

The SOP provides the government with the provision to use Local Registrar of Citizen Registration (LRCRs) to verify names already in the draft NRC while the District Registrar of Citizen Registration (DRCRs) can direct an officer to conduct an enquiry.Furthermore, the state government could also have directed its Border Police Force to recheck an entry. This is because any reference of an individual made by this agency to the Foreigners Tribunal (FT) automatically strikes of the name of the individual from the NRC.

While these are equally arbitrary provisions, they would have limited the need for long distance, last minute inter-district hearings. Why should the applicants now suffer for the government’s lapse?

Moreover, the NRC kendras and Foreigners Tribunals (FTs) are ill-equipped to handle large crowds. There is an absolute lack of basics in these places – sanitation, drinking water, waiting areas, and transportation facilities. Above all, there is a general lack of empathy and love for these victims of the NRC process. In the wider perception, they are de facto ‘illegals’ who ought to prove their citizenship amidst all hassles.

The very fact that a few local activists, such as Soneswar Narah and Pranab Doley, have been helping the distressed people who have travelled long distances for hearing from Lower to Upper Assam itself evinces the state’s failure to ease the humanitarian distress. Such rare interventions show that love and empathy are indeed real possibilities.

This year’s monsoon brought alone a twin disaster – one natural, the other man-made. As floodwaters swept through the state, an entire set of vulnerable people who are at the short end of the NRC found themselves knee-deep in a struggle to safeguard their identity. Both calamities criss-crossed each other at critical points of survival.

The effects of flood is not just when one's home is flooded with water. The real struggle begins after.

The NRC process has not given an inch to the people who are affected by floods for the claims and verification process.

The government’s insensitivity becomes apparent as neither the Attorney General, representing the Central Government nor the Solicitor General, representing the Assam Government, pled for extending the deadline in consideration of the difficulties faced by people to participate in the updation exercise owing to floods.

The Government had rather based its case on the claim of wrongful inclusions and exclusions. It is instead the NRC coordinator who had argued for extension in view of the floods. NRC is turned into a bigger deluge that strips people of citizenship and humiliates the victims.

Two touching stories made into media about how NRC have come to be ranked as a greater disaster this year. The attempts of a man in an open area, in front of what seemed like a relief camp, to dry documents related to NRC spoke volumes of how the proof of an identity was given greater importance over grain or other valuables in life.

The other stories that came to the fore were of people refusing to be rescued from their abode despite being flooded. People are driven around like headless chickens. Many of them will be sent off to the worse off position in the cyclical poverty.

Such shift in reference points in life indicates a deeper erosion of the rational fabric of life. In the first case, we have papers taking over life and in the other, the unwillingness to live is a serious example of erosion of hope and how deep trauma of non-belonging can grip people.

The whole process of ‘claims and objections’ which involves appearing in FTs, travel for hearing to distant places, hiring legal counsel, and losing gainful employment when one is engaged in these processes, among others, pushes these people into poverty, landlessness and even debt. There are numerous examples of people selling their valuables, cattle, and grains in order to meet the ends of the NRC process.

This is nothing but a classic case of dispossession and pauperisation where the arbitrary and inhumane process of NRC will turn them into cheap labourers at the mercy of the business class and landlords.

Journeys and travelling in colonies such as India were marked by the advent of railways and museums, notes political psychologist Ashis Nandy. It signaled a triumph over time and space. Most Indian families in villages and small towns travel distances to meet their relatives. The nodes of travel are marked by the presence and absence of one’s kin.

In contrast, the travels related to NRC and the subsequent deaths are such a dark irony to what Nandy thought of journeys. It signals a deep political and human crisis in our country. At the heart of this crisis is an utter indifference to suffering, an acute death of love and empathy, which overwhelmingly characterises the politics of NRC and xenophobia in Assam.

Assamese nationalism is what made NRC possible and hence, they are certainly party to these sufferings. Who will tell the story of the victims? How long will it take to become amnesiac and oblivious to what the NRC entails?

Why is it that Assamese nationalists only remember the 855 ‘martyrs’ of the Assam Movement as victims? Large-scale pogroms such as the 1983 Nellie massacre are already obliterated from public memory. Will the people who comitted suicide due to the NRC or those who died lonely deaths in detention centres have the same fate?

Whatever may the final outcome of this ruthless exercise be, when the dust settles, the state and its patronisers will have a lot to answer for. The question, however, remains: are there enough people to ask the right questions and demand justice?