Kalpana Kannabiran is a sociologist, author and lawyer. She has taught at the National Academy for Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR), and currently serves as Director of the Council for Social Development Hyderabad.

In this interview with Bar & Bench, she speaks fearlessly on issues ranging from the death of Judge Loya, to the Supreme Court’s recent judgments on Section 498-A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the SC/ST Prevention of Atrocities Act.

Several laws have been enacted to protect the rights of women, children and weaker sections of society in this country. Why does their implementation fall short?

We have not even begun to understand what the annihilation of discrimination means, and I am enlarging Dr. Ambedkar’s idea of the annihilation of caste here to discrimination. The representation of those that belong to the most marginalised sections in institutional structures is abysmal.

In the case of women, look at every rung of the social ladder: where do you find them? To begin with, you don’t find them in the Supreme Court, and I believe this is directly reflected in the judgments of the Supreme Court from time to time.

Why do you say that?

Look at the 498-A judgment. The norm and the normative is always set on the male experience – for judges as much as for laypersons.

I was going to come to 498A a bit later but now that you mentioned it, the order says don’t arrest people until you have investigated the complaint, because the law is at times being misused. What is wrong with that?

It’s the same thing they said about the Prevention of Atrocities Act (POA Act). In fact, when the 498A judgment came, several of us (human rights and women’s rights defenders) said that this was going to set a trend for future judgments. What is the empirical basis on which the Court has accepted the argument of misuse?

It is one thing for the men who have had complaints registered against them (I am not even saying ‘false’ complaints), to allege a malicious complaint in their own defence.

Petitioners facing prosecution can make the wildest allegations, and we saw that in the Prevention of Atrocities case as well, without any basis. But how can the Court accept public morality over Constitutional morality, that too without an empirical justification? This easy acceptance of dominant norms points to the possibility that judges are trapped within a dominant, hegemonic worldview and mindset.

I have studied judgments on rape from the 1950s till the present. It is shocking to see the kind of language that the judiciary uses to describe rape, with a few minor exceptions. Even the revered Justice Krishna Iyer, who was against the death penalty, and took celebrated stands on a number of rights issues, called rape an “adolescent exercise” in one of his judgments. But that pales into insignificance when we compare it to some others. There is a deeply entrenched complicity in dominance that destabilises the most progressive legislation – destabilises even the Constitution.

When you say “forces of dominance” can I take it to mean those in the highest echelons of the three pillars of the State?

I mean the ways in which state power is bolstered by social and political power on the ground – by a social compact, that sanctions violence against the marginalised. Courts are often complicit in this.

Look at the Suresh Kumar Koushal judgment or the Kerala High Court judgment in the Hadiya case. Kerala is touted to be one of the most progressive states in the country, touted to have found the magic potion to make women equal. Look at the mess the state has made in Jisha’s case and in Hadiya’s case.

The perilous moment is one where there is no separation of powers. We see that increasingly today. Right from state authorities to the police to the judiciary – they are indistinguishable from each other.

Judge Loya is a case in point. For me, it is a case about the marginalised and the course of justice. Judge Loya was hearing a case pertaining to a victim who was being hunted for being from a particular community. It was an extrajudicial killing, a targeted assault, and Judge Loya was targeted for daring to adhere to judicial procedure and the rule of law.

The Supreme Court’s declaration that the four High Court Judges who made statements on Judge Loya’s death are beyond reproach, that the bonafides of the petitioners are suspect, and that asking for a full and fair investigation is an attack on the judiciary — is a clear illustration of social compact which includes buying into politics of a certain kind.

The petitioners in the Loya case never presented any hard evidence of there having been a crime committed or any other sort of wrongdoing. All they said that it was suspicious, and most of the petitions were based on a media report. What do you have to say about that?

If it is suspicious then it needs to be investigated. By the time the case came to the Supreme Court, a number of loopholes and discrepancies surrounding Judge Loya’s death had come to light. Did they even look at what was placed before them? All they did was question the bonafides of the petitioners. This has become the easy way out at a time when a right-wing majoritarian government sets the parameters for justice — question the bonafides of anyone who dissents and celebrate those who kill those who dissent with impunity.

Isn’t it premature to say that Judge Loya was killed in the first place?

Well, we – as citizens and human rights defenders – are putting the onus on you. You show us that he was not killed. I really think this is a citizen moment, where one has to turn it around and say, we are charging you on the basis of what we believe is evidence, or pointing you towards the big holes in your story. You demonstrate to us, on what basis we are wrong in our allegation. I am not willing to accept that just because you are a judge what you say is right. This is the civil liberties method – fact-finding. The petitions were painstakingly put together after having gone through several accounts of the incident and related reports. How is it that you did not bother to look at any of that?

Coming back to the question of marginality and the rule of law, Justice Basu and I were part of a team that did several sessions with 300 judicial officers in undivided Andhra Pradesh between 2004 and 2006. Repeatedly, the account that we heard from serving officers was that the CrPC has enough and more provisions that offer effective protection to complainants, witnesses, accused, investigators. But if you don’t allow judicial officers to function as they should, what is the use of having a good CrPC or special legislations where you have expanded the definition of caste atrocity and rape?

When you say “you” don’t allow the judiciary to function, who are you referring to?

I speak of interference from those in political power, who are aligned with and often belong to the dominant castes, the majoritarian community, and inevitably male.

This may happen in the lower judiciary, but do you think the higher judiciary can be influenced as well?

I think it was Professor Upendra Baxi who observed that the descriptors “lower” and “higher” judiciary do not make sense. It’s just a matter of different jurisdictions. There are courts with original jurisdiction and those with appellate jurisdiction; and there are different branches of judicial institutions presided over by judicial officers/judges, as the case may be. By saying “lower” and “higher” you are creating a hierarchy and naturalising the attributes in that hierarchy – i.e. the higher is more meritorious than the lower. The good old graded inequality, to invoke Dr. Ambedkar yet again.

This is not true. The reality, in fact, is quite mixed. The issues before us today don’t concern the magistracy. All of them concern what you call the “higher” judiciary. The four judges who held a press conference in January did not express views against the “lower” judiciary. Judge Loya on the other hand, was part of the “lower judiciary”. We can multiply examples, but I rest my case.

Coming to special legislation like the POA Act and Section 498-A. Let us set the empirical basis for misuse aside for a moment. These were legislations where the arrest was mandated without investigation of complaints. Given that fact, do you think some good came out of these orders?

No, absolutely not. The reason why such legislation mandates arrest prior to investigation is precisely because of the way in which these atrocities happen. I have lived through the times of the Chunduru and Karamchedu massacres and any number of others. Countless cases of domestic violence, murder of wives and cruelty for reasons of dowry.

It is impossible for a complainant to proceed with the complaint if the accused is at large. It is impossible not only for fear of intimidation, but there is a real danger to life. A lot of times we totally underestimate the power of caste and majoritarian dominance.

These are violent people who have an utter disregard for the law and are asking to be treated outside the framework of the law – which means don’t arrest even if the law mandates it.

If you look at the Supreme Court’s decision on the POA Act, what I found striking was that the use of words like “malicious complaint,” “malicious prosecution,” “malicious complainant”, “instrument of blackmail” “personal vengeance” and settle scores arising from “personal vendetta”, by “scheming, unscrupulous complainant” – all of the accusatory terms target the SC or ST complainant; “unsuspecting,” “innocent” etc. by default only fall on the non-SC or non-ST.

As a judge, you know when you are making these statements that complainants under the POA Act can only be SC or ST. Is that not targetted abuse of an SC person? You are doing it willfully and with full knowledge in the written text of the judgment, using your power as a judge to make demeaning statements against a certain class of people. The use of power to target an SC person and verbal abuse specifically targeting persons belonging to Scheduled castes are both covered under the definition of “atrocity” under the Act.

Ironically, at no point in the entire order does the Bench link the POA Act to Article 17 of the Constitution. The POA Act is not merely another special legislation. It is a special legislation that flows from the Constitutional Protections in Part III against untouchability and caste discrimination. How was it possible that the two were not linked by the Court in its interpretation in this case? Dr. Ambedkar was misquoted – the selective and distorted use of his words was deeply troubling.

I am really worried. Our Constitution is no longer in the hands of those who instill any confidence that they will protect it. Justice HR Khanna was resurrected and celebrated in the right to privacy judgment, and ousted from judicial memory in the more recent ones we have spoken about.

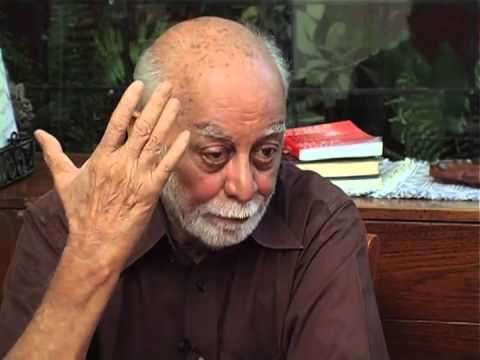

What prompted you to study law? Can you tell us about how your father influenced/inspired you to do the kind of work you do?

My primary discipline is Sociology. My encounter with the law happened much before I studied it. I did go on to study it and get myself a teaching degree but that was much later.

I grew up in a home where fact-finding missions, encounter deaths, illegal detention of teachers and students, torture by the police during the Emergency were discussed in our drawing room, at our dining table and with friends who visited. Rameeza Bee who was raped in police custody and her husband killed in custody was around my age and I watched my father piece together the evidence to present before the Muktadar Commission. The witnesses to torture and encounter deaths during the Emergency stayed at our home before being produced before the Bhargava Commission.

And my father knew no fear. My mother didn’t either. And both of them always discussed their work in our presence. So we children imbibed the law – the Constitution – in our everyday life at home. But beyond that, my father was my teacher and my best friend. In fact, he is to date my only teacher – the only one who has imparted learning and who learnt from me, and my questions.

I watched him speak firmly, gently and persuasively with his clients; I sat in on his discussions; I followed his gaze at his bookshelf, to see which book he was obsessing about; followed his markings in texts, and tried to understand why he had underlined what he did and read his written arguments to understand how one might build a reasoned argument. On any issue. I learnt the ethics of work from him.

There has been a crackdown on dissent across campuses in the country. Your views on why this is happening and how the trend can be bucked?

What is happening on campuses is part of what is happening in our country today. The rise of a new imperialism and colonisation in the name of religion – and all other forces are aligned with this.

Seventy years after independence, I would say we need a second freedom struggle to liberate ourselves from the capture of our country and collective conscience by obscurantist, violent politics and governance. We need a deep reinstatement of our Constitution. It is a challenge for citizens and courts alike.

And students and campus communities across the country must continue to be at the forefront of this resistance because universities and higher education are major targets of this colonisation.