‘Once in a while an artistic practice emerges which challenges viewers in new ways that cut through the noise, and offers something both deeply familiar and at the same time utterly new. Collaborative, creative, and experimental, Gill and Vangad, in Fields of Sight, provide a new language for art practices that address the politics and aesthetics of environmental destruction. Ecocriticism comes alive through the conjoining of photography and Warli painting, hoping to replace one modern history with another history, one that is contemporary. If the modern is marked by notions of progress, development, and nationalist discourses of decolonisation, the contemporary moment, with its rampant inequalities and environmental destruction, calls for a politics outside of the modernising narratives of the nation-state.’

Inderpal Grewal

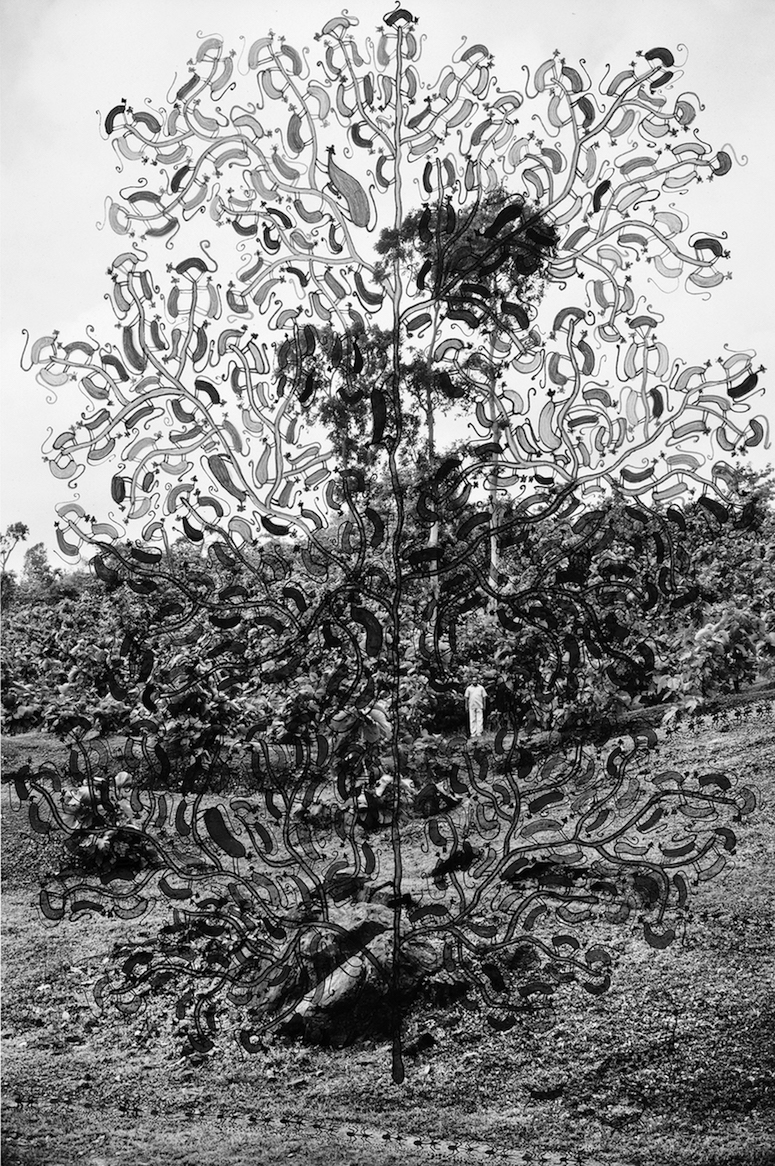

‘Tree of Monkey Ancestors’, 2015, 24 x 16″, ink on archival pigment print

‘Tree of Monkey Ancestors’, 2015, 24 x 16″, ink on archival pigment print

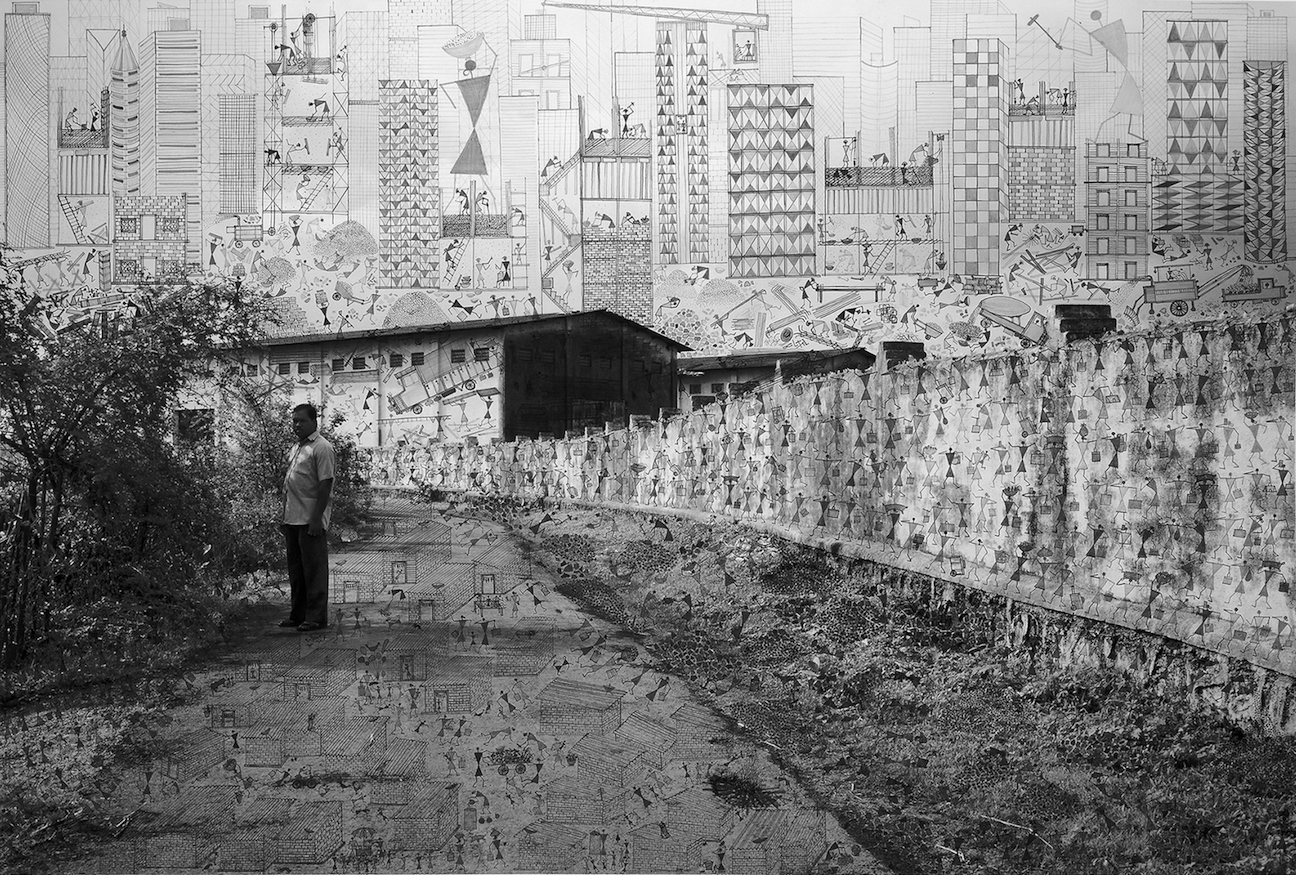

‘Building the City’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

‘Building the City’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

‘The Drought, the Flood’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

‘The Drought, the Flood’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

‘Factory and River II’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

‘Factory and River II’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

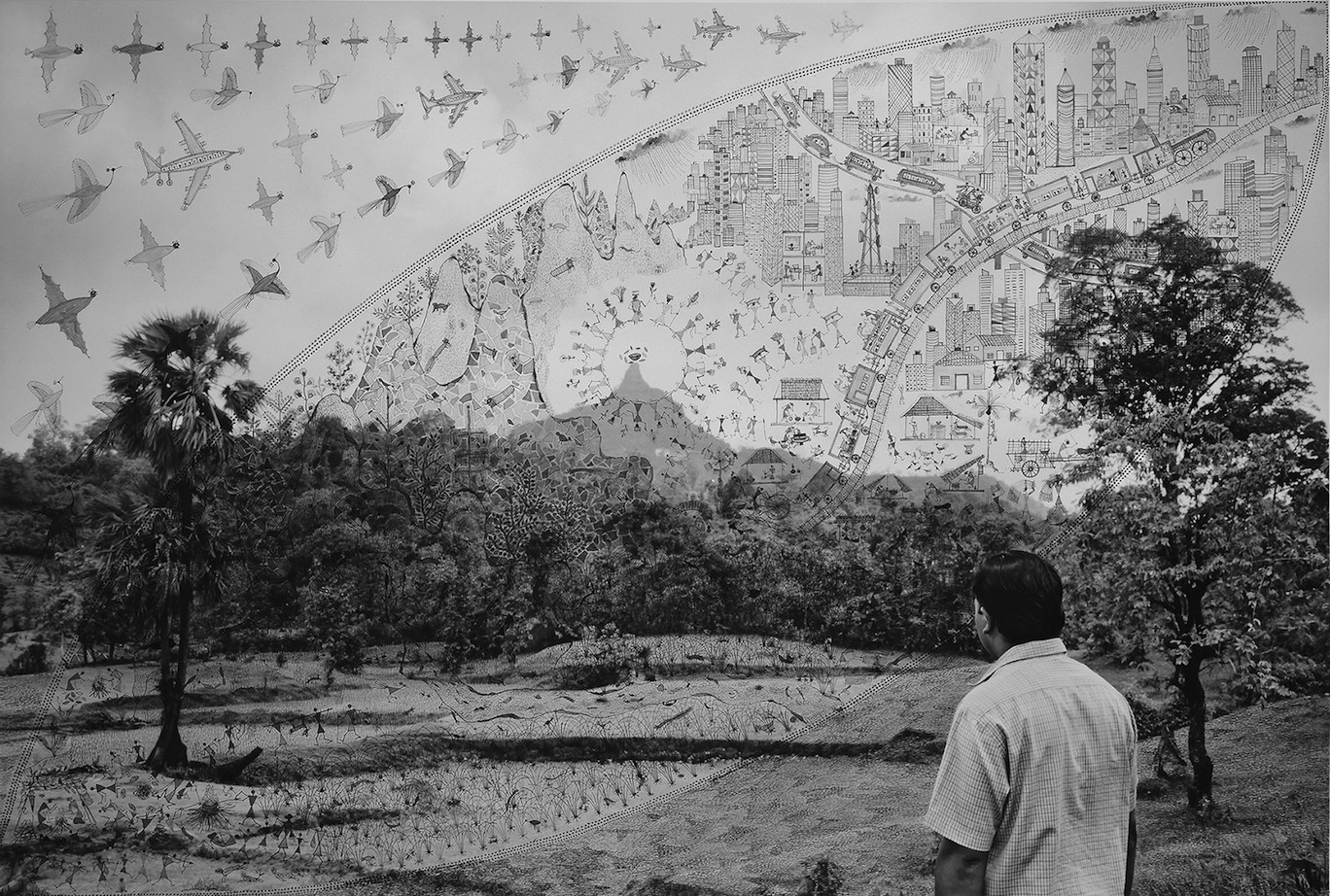

‘The Eye in the Sky’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

‘The Eye in the Sky’, 2016, 42 x 62″, ink on archival pigment print

Another Way of Seeing

In early 2013 I spent some weeks in Ganjad in Dahanu – an Adivasi village in coastal Maharashtra. I was invited to live in the home of a well-respected artist, Rajesh Chaitya Vangad, and to create work in and for the local primary school.

In the course of my time living in Ganjad and working on the school project, I began to appreciate the landscape; only some hours away from Bombay, it was nonetheless completely distinct. We were living within nature, which, chameleon-like, had so many faces – changing even as one took a turn. There was no electricity for hours and nights altogether, and the Airtel only worked when you climbed a little hill.

Undistracted, one’s awareness was sharpened. I wished to extend this awareness through photographing the landscape, but it felt distant, even opaque. Perhaps the beauty was a barrier, or perhaps I had simply not spent enough time there. In conversations with Rajesh, whose family has lived for generations in Vangad Pada, working as artists, we began to discuss his village.

Any place looks entirely different to different eyes. I was made acutely aware, once again, of how a place is assigned meaning only by its viewer, determined perhaps by her relative distance or proximity to it; and of how viewing itself is an essentially solitary act, since what we see might be only a projection of what we know, have already seen or experienced prior. As someone wise once said, to one man’s eye the pond is full of beautiful lotuses to admire, to another’s it contains mighty fish to eat.

Tentatively, I decided to photograph places significant to Rajesh – often with him present in the frame. He would take me to these special places, and I would decide where and how to construct the image, what to include within it, how to work with or against the light, how best to frame him within the landscape and so on. It was a set of pictures about his place, a map determined by Rajesh, and formally constructed by me – photographer as cartographer.

When I later saw my contact sheets, I realised that so much of the narrative that I had received from Rajesh – the great stories, which had made it come alive for me – was missing. Part of it, I realised, was the limitation – and perhaps, the unique presence – of photography, which restricts what is in the image to ‘now’. How could I convey what happened in those months in the 1970s when the violent mobs of a powerful political party raided the village and the locals fled and fell upon each other in terror; or the particular full moon night in October when a great forest on one hill comes alive, and all the people who spend that night in the forest see shining eyes glitter around them, as even the most dangerous animals are benign when everything glows from the aura of the moon; or the stories of great overlords who come calling in secret to the homes of innocent, hospitable men, bringing gifts and drink and returning with deeds of land; or the mythical stories that encompass everything that has come or is yet to come.

So we decided to collaborate in a more active way. Rajesh would inscribe his drawing over my photograph, meet my text with his own. Or I would construct a photographic scene or set, in which he might stand and speak. Over the course of the last years, through works mailed back and forth between Delhi and Ganjad and subsequent meetings, we have made and selected several photographs and worked on them to reflect the narratives that arise from our conversations. We restricted our work to a monochromatic palette to make the encounter more intense and precise. The final work is created over a period of many months spent together in my studio in Delhi, in different spells.

This commingling work may be seen as an encounter between two artists of about the same age with entirely different languages – one with ancient antecedents, the other more recently originated; and the histories, politics and world views embedded within the expression of those forms. Rajesh’s language, constructed with stick and brush, unfolds entirely from an encyclopaedia of forms in the mind, which emerge to reflect the world, memory and myth: wind, disease, apocalypse – anything is summoned forth at will. In my own language, constructed by camera and negative, the world itself is the encyclopaedia, and I recognise and edit existing structures to reflect what is apparent in my mind. The final work contains parallel projections of place; using perspective, negative and positive space, tonal values and relative dimensions, it merges fields of sight, and of perception. If you stand here, you might see it this way, if you move just a little, another world unfolds.

Gauri Gill

I am a creation of my stories, which live in my work. There are at least sixty stories I know. They concern gods, kings, man, the earth, Mahadeva, Parvati and the gods of the hills. This particular story was told to my father’s father by his brother. He relayed it to my father, who told it to me. I believe it was prescient, that it foretells the future. It encompasses so much of what we see today: earthquakes, cyclones, tsunamis and all kinds of destruction on earth. Why do we farm, when, and how, in how many days and in what ways must the farmer till his fields, all of this is in the stories. It manifests constantly in my work:

Once, there were four hunters. Each hunter came from a different direction and represented a different portion of the whole – North, South, East and West. Each one went to the forest to hunt. The hunters did not know each other and went there on their own. Hunting, they roamed from forest to forest, until they were in the deep. One day, in a clearing, the first hunter encountered the second and asked him, who are you? The second hunter answered: I am a hunter, from the South. The first hunter replied: I too am a hunter, from the North. The two decided that since they were both hunters, they would hunt together. They continued their journey.

As they travelled, the two encountered the third. They asked him: who are you and where are you from? He replied: I am a hunter, from the East. They invited him to join them. And so they continued.

Like this days and nights passed. One day, they went to a big jungle to hunt. There they met the fourth hunter. In answer to their question about his antecedents, he replied: I am a hunter, from the West. The four decided to continue together, hunting as they moved deeper and deeper into the forest.

When they finally arrived in the very dense core of the jungle, they could not find anything to hunt for two full days. So they decided to find a place where there was water and a tree’s shade to rest in. They spotted a large Bael tree, and a stream flowing nearby. As they went closer, they saw a hut near the tree. As they moved even closer, they saw a sadhu near the hut. They greeted him respectfully, and he asked them how it was they had come to the deepest part of the jungle. One replied: We are hunters of four separate directions, and met while hunting; hunting together, we arrived here. They asked if they could spend the night in the hut. The sadhu answered in the affirmative. All four of them cooked some food, ate and slept.

In the morning, before the sun had risen, the four went off in four different directions to do their morning ablutions. When the first hunter reached the river, before bathing he saw a cow give birth and eat its offspring immediately after. The first hunter was astonished at the sight.

The second hunter went in another direction, where he saw two large trees. In one he saw a beehive. Before he could begin to bathe he saw an elephant eat all the leaves of the tree, only to discover his tail was now stuck fast to the hive. No matter what he did, he could not dislodge it. The second hunter was astonished at the sight.

The third hunter made his way to bathe, but before he could do so, he saw the large mountain before him begin to slowly melt into water. As dawn rose, he saw the immovable mountain, with all the men, animals, trees and plants upon it, become water and flow into the river. The third hunter was astonished at the sight.

The fourth hunter, before bathing, saw before him a greater mountain, with men and animals, trees and plants, begin to crumble from one side, even as it caught fire. As it was being destroyed various gods tried to stop it, but they were unable to do so. Finally, a god managed to halt the destruction with the point of a needle. The fourth hunter was astonished at the sight.

All four returned to the hut, and told each other what they had seen. When they arrived, the sadhu was praying to Mahadeva. The hunters decided not to hunt that day, and instead told the sadhu the full story when he had finished. When the first hunter relayed his sight, the sadhu replied: Don’t trust anyone in these times. When the second hunter relayed his sight, the sadhu replied: Even the strongest man is able to get snared by small things. Therefore, walk carefully. When the third hunter relayed his sight, the sadhu replied: The earth is at risk from wind and water. When the fourth hunter relayed his sight, the sadhu replied: On this earth there is very little truth to be found.

Rajesh Vangad

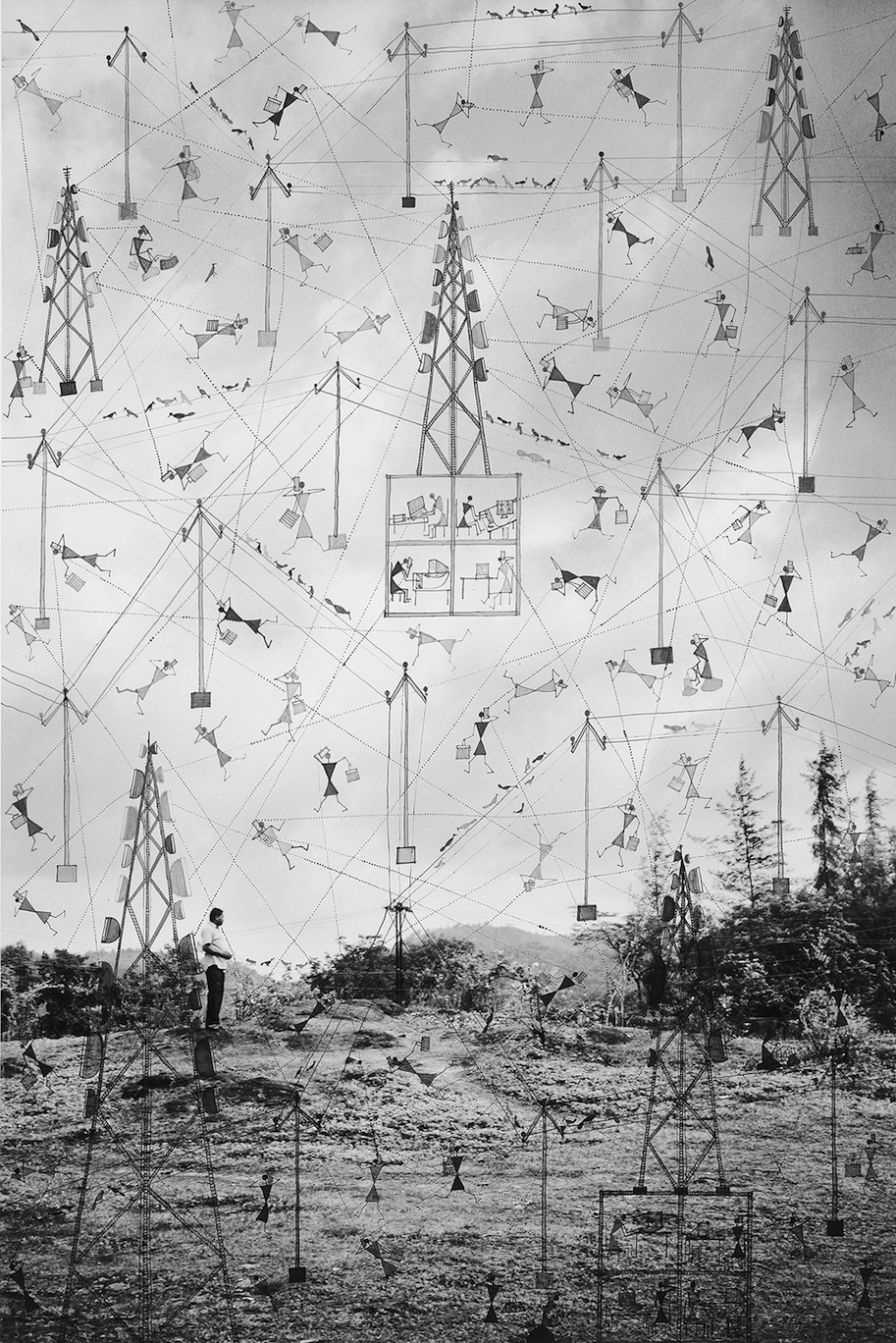

‘Paths through Air’, 2015, 42 x 28″, ink on archival pigment print

‘Paths through Air’, 2015, 42 x 28″, ink on archival pigment print

‘A Forest of Trees’, 2015, 62 x 42″, ink on archival pigment print

‘A Forest of Trees’, 2015, 62 x 42″, ink on archival pigment print

Inderpal Grewal writes on Fields of Sight

Once in a while an artistic practice emerges which challenges viewers in new ways that cut through the noise, and offers something both deeply familiar and at the same time utterly new. Collaborative, creative, and experimental, Gill and Vangad, in Fields of Sight, provide a new language for art practices that address the politics and aesthetics of environmental destruction. Ecocriticism comes alive through the conjoining of photography and Warli painting, hoping to replace one modern history with another history, one that is contemporary. If the modern is marked by notions of progress, development, and nationalist discourses of decolonisation, the contemporary moment, with its rampant inequalities and environmental destruction, calls for a politics outside of the modernising narratives of the nation-state.

Denuded landscapes, infested and opaque waters filled with sewage and chemical sludge, garbage dumps, abandoned houses and communities have all become the new critical language of environmental photography as political art. The images present us with an aesthetic of the lost landscape, trying to evade the inevitable pleasure of photographic capture or that frisson of pleasure in destruction. Photography’s relation to death and time, in Roland Barthes’ formulation, became allied to this aesthetic language of ecocriticism. Yet so many of these practices inevitably succumbed to the sublimity of empty landscapes of ‘nature’, or the aesthetic of the picturesque as histories of nostalgia for landscapes that can be controlled (even to look natural). Breaking from this language, Vangad and Gill mix media, languages, stories, modernities in a collaborative project that defeats the reinscription of the history of landscape art and the valorisation of an empty construction of ‘nature’ in both painting and photography.

Fields of Sight populates the contemporary photograph with narratives and figures that fill the landscape, reaching up to the sky, visually claiming presence rather than loss. The photographs create landscapes of environmental destruction, and are critical of what is taken as the progress of industrial modernity. But what is lost is not nature or emptiness – as images that claim to participate in ecocriticism often demand the viewer to fill up the emptiness with her own loss. Fields leaves us no such space or opportunity. Gill’s landscapes in black and white position Vangad at their centre, not simply as collaborating artist/ painter but also as narrator, and he takes over to repopulate the so-called lost landscape. Decentring the perspective of power, Vangad’s presence – often with his back turned to the viewer, blocking her ability to see him, replaces that perspective of power with another one, Vangad’s own. He paints fully, much as he might paint walls, houses, and other canvases, but this is not a distant space, it is his own village and land. Vangad’s painting covers the photograph, populating the landscape with stories of loss, power, ethics, and the politics of land that come from his history, his language, his community.

Vangad’s prolific and intense figures make demands on the viewer. Warli iconography and landscape photographs merge in a critical language that remakes each medium. We must not remember the lost landscape in terms of pristine worlds, picturesque lands, ‘natural’ worlds empty of people not lost through the coming of other people, but rather through the narratives and worlds of those who have been displaced, seen as non-modern, unfit to be part of the modern state. There were other worlds, Vangad and Gill tell us, other people, other lives and stories… They are there, not gone, not past. Vangad is in the landscape, not simply of it. The photograph captures him in the place that is his own, but the language of the photograph is not the only one that can speak for him.

His painting constitutes and inscribes the particularity of place, the history and cosmology of his community. He inhabits and reinhabits, covering all the available space of land and sky of the landscape photograph. There is no demarcation between land and sky, all are filled with his stories, nothing is left to profit and production; the only utility possible is that of his stories. He demands we look at him, through him, at images, narratives, stories, lands, worlds – his old school, the land altered, the factories spewing black smoke. But looking through him is not simple: it is demanding, asking us to look closely, decode, decipher, listen, and decolonise. Gill’s photographs become both a setting and a match for Vangad’s intensities.

At the same time as Vangad and Gill embed their new form within a historical Indian practice of the painted photograph, they depart from it as well. Refusing to paint over with colour the black-and-white photograph, they paint with the same palette but with different intensities, languages, shades, and figures. There are no brilliant colours here. What draws the eye are the sombre shades of black and white and the combination (not melding) of divergent styles and languages.

Vangad and Gill merge the medium of the black-and-white photograph with the more traditional Warli use of figures and icons in white pigment. The starkness of drawing and painting with shades and textures works not simply to disavow modernity or erase it, but also to remind us of its uses and costs – and not why it must not be an end in itself, but rather, why its limits must be recognised.

We see here a photographer of and from contemporary, urban India (though of a land-centred community herself) and an artist/ painter of the Adivasi community from Maharashtra whose visual narratives work together to tell stories that demand to be heard as equally contemporary, not as relics of a traditional or ‘tribal’ past, a term the British as well as independent India have called Vangad’s communities. He is not a ‘lost’ figure of what Renato Rosaldo called ‘imperial nostalgia’, asking us to mourn what we ourselves have destroyed. He is not destroyed; he is there, producing a language and art practice that uses the modern medium and its technologies – the photograph, the motorcycle – to assert presence rather than to provide the possibility of mechanical replication of that which is lost.

The artistic practice here is one of a demand, a challenge, to recognise rather than to mourn. Vangad and Gill together re-create in a new language the practice of collaboration of the painted photograph. The past is narrative, but narrativising continues, through mixing the historical and generational practices of Warli painting into the language of the photograph. It is a critical language of demand and recognition, the moment of the photograph now embedded in a plethora of voices, languages, and histories, in the ongoing production of attention, of new ways of seeing.

‘The Sweet and Salty Sea’, 2015, 62 x 42″, ink on archival pigment print

‘The Sweet and Salty Sea’, 2015, 62 x 42″, ink on archival pigment print